If I am sliding uncontrollably down a steep embankment headed for a cliff, I won't look for a ladder. I'll flail and clutch for anything--animal, vegetable, or mineral--to get hold of and arrest the fall.

Saturday, December 16, 2017

Saturday, November 11, 2017

Veterans are expected to say something about Veteran's Day

on Veteran's Day.

Normally, I go on a kind of tangent about militarism and epistemology. This year I'm leaving all poking and sniffing and bloviating around the Veteran-as-signifier, to others. Because the signifier Veteran on Veteran's Day is contrived as a prop to show the sacredness of war. At the very inner core of our national rituals valorizing The Veteran is the love of war.

Wars are carried out by armed organizations, generally understood as the military, though there is a long menu of differing armed organizations engaged in a diversity of forms of war. Those organizations are comprised of humans, mostly male humans, but more and more including a female fraction as well. What does war and the preparation for war do to those people who are in those organizations?

Normally, I go on a kind of tangent about militarism and epistemology. This year I'm leaving all poking and sniffing and bloviating around the Veteran-as-signifier, to others. Because the signifier Veteran on Veteran's Day is contrived as a prop to show the sacredness of war. At the very inner core of our national rituals valorizing The Veteran is the love of war.

Wars are carried out by armed organizations, generally understood as the military, though there is a long menu of differing armed organizations engaged in a diversity of forms of war. Those organizations are comprised of humans, mostly male humans, but more and more including a female fraction as well. What does war and the preparation for war do to those people who are in those organizations?

Sunday, October 29, 2017

Wednesday, October 11, 2017

Wednesday, September 27, 2017

"whore"

He is a media whore.

She is a corporate whore.

They are all publicity whores.

We've all heard it. Many of us have said it. Some may ask, what is the problem?

She is a corporate whore.

They are all publicity whores.

We've all heard it. Many of us have said it. Some may ask, what is the problem?

Wednesday, September 20, 2017

Shawn Aghajan's review

Stan Goff, Borderline: Reflections on

War, Sex, and Church (Cambridge: Lutterworth, 2015). xxiii +

446 pp. £32.50. ISBN 978-0-7188-9407-8 (pbk)

Reviewed by: Shawn Aghajan,

University of Aberdeen, UK

The

first four sentences of Borderline

neatly summarize its theses: ‘War is implicated in masculinity. Masculinity is

implicated in war. Masculinity is implicated in the contempt for and domination

of women. Together, these are implicated in the greatest sins of the church’

(p. 1). The fact that a Christian pacifist penned these lines is unsurprising.

More remarkable is that their author is also a retired Special Forces sergeant

in the United States army whose 24 years of service took him to Vietnam, Guatemala,

El Salvador, Grenada and Somalia with a brief stint on the faculty at West

Point. Stan Goff’s CV explodes the common charge levelled against pacifists that

they are only able to keep their consciences clean by letting others get their

hands dirty with the morally sordid necessities of war. Goff would readily

confess that neither his conscience nor his hands are clean, and this helps to

explain why, after his conversion at age 56, he has come to understand

non-violence to be an inextricable part of what it means to be a disciple of

Jesus.

Goff rejects violence, not because it is ineffective—history is rife with examples to the contrary—but because it is an idol of the powerful, something to which Christians have no intrinsic claim. He argues that though masculinity is a malleable cultural construct, the historically consistent identifiers of what it means to be a man are the subordination of women and execution of war—essentially two sides of the same macho coin. Jesus’ question to Simon the Pharisee, ‘Do you see this woman?’ (Lk. 7:43a) is the leitmotif weaved throughout the book in order to challenge from several different directions what Goff considers the myopic male wielding of power over and against women. The borderline from which this book draws its name is the arbitrary one drawn between genders, races, classes and nations that historically has been defended vigorously by means of violence. Goff writes that for the Christian such boundaries have been abolished through the death of Jesus, who offended so many precisely because he traversed these barriers. The cross is the only truly redemptive violence in history, though the powerful often recast their use of violence in salvific language.

Goff

illustrates in some detail how popular films as well as a selective historical

memory continually underwrite the legitimacy of the American version of the

myth of redemptive violence. It is no coincidence that the American Western

became increasingly popular after World War II, Goff explains. The images of

cowboys gunning down bandits, subduing lawless ‘Indians’, and rescuing helpless

women tied to train tracks served to reinforce the American belief in the

necessity of the armed strong man to keep society safe from villains. The

Western resonates with America’s perception of itself as the sheriff in the

white hat providing peace through force to the helpless in the midst of a

dangerous world. This trope did not fade with the waning of Westerns’

profitability. Movies since 9/11 like Man

on Fire and Zero Dark Thirty

remind viewers that sometimes the only recourse for heroes is to resort to

morally dubious violence like torture in order to right an injustice suffered,

and this is not necessarily a bad thing.

Hollywood

is not the sole propagator of faith in redemptive violence and its corollary,

the male prerogative to wage war. Goff draws his readers’ attention to the fact

that the US Department of Defense has also produced its fair share of

pernicious fiction. To illustrate this point, he juxtaposes the stories of

Jessica Lynch and Pat Tillman. In the government’s sanctioned fiction, Lynch

was captured by the Iraqi army in a firefight and then interrogated and

tortured in her hospital bed, before being ‘rescued’ by Special Forces in

another heroic firefight.

The

actual narrative does far less to corroborate America’s confidence in its own

moral rectitude in war. By Lynch’s own account, she was neither interrogated

nor tortured in the nine days she was in the Iraqi hospital. The US army’s

mendacity was compounded by the drama that it orchestrated in staging Lynch’s

rescue. Despite knowledge that enemy soldiers had withdrawn from the hospital,

US forces cut power to the hospital, blew open its doors and handcuffed doctors

and patients. Uncharacteristically, the operation was recorded by the military

and the edited video was released the very next day. Six months later Hollywood

followed suit with its own made-for-TV movie.

Goff

draws attention to the irony that the memory constructed by the US army spin

doctors and media that lapped it up was hardly blemished by being exposed as a

fabrication because the little white lies they fed the public reinforced all

the appropriate hierarchies. Lynch, who was made an honorary male by her

participation in the military and willingness to fight to the death, resumed

her rightful role as damsel in distress at the hands of the sub-human Iraqis.

This set the stage for the heroic rescue by Special Operations, ‘the epitome of

moral American manhood’ (p. 186). The fact that the story of Lynch was seized

upon by both feminists and anti-feminists to advance their own agendas

concerning the fitness of women for combat only serves to underscore Goff’s

claim that we do not see this woman, merely her utility within debates about

gender and violence.

If

Lynch’s ‘rescue’ reinforces the American ideal of women in combat, Pat Tillman

is her masculine counterpart. After 9/11, Tillman opted out of a lucrative

contract in the National Football League to enter the military. This initial

sacrifice and his subsequent service in Afghanistan epitomised the virtuous and

selfless citizen fulfilling his duty to his country. Yet Tillman’s service

would ultimately require giving his life, and he was posthumously promoted to

corporal and awarded a silver star for valour in action against the enemies of

the United States.

The

problem with the military’s account of Tillman’s death is that it was not true,

and people at every level of the army’s chain of command knew it. Tillman was

not killed by the enemy but by ‘friendly fire’ from his comrades. Telling the

public the truth about Tillman’s death was not a prudent public relations move.

This was an exceptionally poor time to be candid for a military that, only a

day earlier, had gone into damage control when its improprieties at Abu Ghraib

were made public. The depth of this deception is revealed by the fact that the

lingering public recollection of Tillman’s death (to the extent that it is

remembered at all) is primarily one of a ‘good American son’ who made the

‘ultimate sacrifice’, with the other aspect of his story erased: a duplicitous

military that blatantly attempted to cover up its own failures. The former

story reinforces the national narrative that the sacrifice required for freedom

is no less than the death of a nation’s children on the altars of just wars

around the globe. The truth casts serious aspersions on this understanding of

citizenship.

Goff

traces the origins of American willingness to make such sacrifices (or at least

finance the sacrifices of others) to the sacralizing of the nation after the Civil

War in which, ‘Manliness was consecrated with a blood sacrifice, and the blood

sacrifice of the nation came to

supersede the blood sacrifice of Jesus. The nation became the new deity’ (p.

169, emphasis original). As a result, he argues, the church offered little

resistance to the de facto ‘outsourcing’ of its moral decision concerning

warfare to the state, understood in Augustinian terms as the ‘providential’

guardian of the ‘common good’. What would be unintelligible, however, to

Augustine and any subsequent just war accounts is the legitimation of total war

for the survival of the state. Goff contends that contemporary wars are

inevitably total wars as evidenced by the fact that they kill more civilians

than soldiers (he defends this claim by citing the BBC’s statement that by the

end of the twentieth century, 75 per cent of war casualties were noncombatants;

p. 112).

What

moral sleight of hand is needed to convince one’s citizens that fighting for

the common good necessitates that three civilians die for every professional

soldier killed in combat? Goff suggests that the American answer to this

question is found in the Lieber Code, ostensibly written to reign in unjust

combat practices during the Civil War. Any limits the document sought to impose

on war were hamstrung by its allowance for their circumvention due to ‘military

necessity’. This exception, vaguely delimited as ‘that which is indispensible

for securing the ends of the war’ (p. 167), could outflank any moral criticism

of questionable practices in war as long as the tactics could be portrayed as

obligatory for winning the war. Goff insightfully observes that the Lieber Code

is the elastic boundary that could be stretched to cover any multitude of

transgressions, so it is unsurprising that it became ‘the loophole through

which Sherman would ravage Southern farms in 1864, and through which twenty-two

thousand Dresden civilians would be firebombed to death in 1944, and through

which fell two atomic bombs on Japanese cities’ (p. 168). The Lieber Code, like

other attempts to write ethical warfare into law, tacitly formalised the belief

that war could be either just or effective but not both.

Borderline

is a substantial argument bolstered by autobiographical, feminist,

philosophical, cultural and theological voices. Critics may charge that in

trying to evaluate the problem of war and gender from a variety of angles, Goff

has failed to treat any of them adequately. Philosophers, anthropologists,

theologians and military personnel, as well as feminists from each of these

disciplines, may find Goff’s analysis of their field to be too selective or

thin an account to be useful. In his humble, self-deprecating style, he would

likely own these criticisms while defending the necessity of each vantage point

to ‘explain why masculinity constructed as domination, in war and in relation

to women, is really just one story … of manliness … [T]his very construction has steered the church away from the story

of the Gospels’ (p. xvi, emphasis original).

Goff’s

unique experiences enable him to narrate this story (often with lurid details

and ‘salty’ language that may make some readers uncomfortable) from a rare

perspective that few civilians could access on their own. It cannot be easily

dismissed as a flaccid, pacifist indulgence in an over-realised eschatology.

Rather than relegate justice to the ‘sweet by and by’, Goff’s account gives

Christians sufficient cause (and the tools with which) to interrogate

contemporary accounts of gender and warfare. Such a thesis casts significant

doubts on the notion that Christians can imbibe the dominant cultural myth that

national exceptionalism is justly defended by violence without compromising

their witness. Even if the reader thinks Goff’s portrayal of the sacralizing of

the state is hyperbole, it is difficult to contend that the American desire for

security and its subsequent faith in its military power to provide that

security by any means necessary does not come precariously close to idolatry.

Goff reminds his readers that what differentiates Christians from the ‘ideal’

citizen is that, ‘We are not called to be powerful.

We are not called to be respectable.

We are not called to be patriotic. We

are not called to be masculine. We

are called to be holy’ (p. 400, emphasis original). If Goff’s account of

Christian calling is true, Jesus’ disciples should be leery of entreating the

protection of the very golden calf we have formed from our own treasure,

because in doing so we may very well be calling down judgement upon ourselves.

Monday, August 28, 2017

Caligula on the Hudson

Trump and the Erasure of the Republican Party

Like a

child-king incapacitated from a lifetime of indulgence by bullied servants,

Donald Trump is quickly ripping the Republican Party asunder. His sinister calculations,

aimed by a coterie of crackpot advisers at being America’s own Duce—like the

neocon Bush-clique fantasies of democratizing the oil patch for Yankee capital—has

had its opposite effect. The party he commandeered through a hostile takeover during

last year’s election follies has technically won both houses of the federal

legislature and the executive branch; but contrary to capitalizing on that

newfound power, it is metamorphosing into a political calamity.

Saturday, August 12, 2017

Charlottesville

Like 9-11. Levittown. Nagasaki. Kristalnacht. Kennedy Assassination. 2007 Crash. 2003 Iraq Invasion. All these black swans, historical pivot points. Punctuation marks on the narrative that replaces memory as history. Is this gonna end up being a thing now? Charlottesville? Another punctuation mark on our wretched history?

These are fearful times. Donnie has discovered there are nukes in the closet, and he wants to boardgame with them in Korea. And his alter -- Kim Jong Un -- seems to be as possessed by masculine blustering as Agent Orange. Really, y'all. This is for-real pretty scary. And what's motivating the process right now is probative masculinity.

Charlottesville.

Apparently White Nationalists are rampaging through the city, confronting counter-protesters, some peaceful, some provocable, some likely themselves provocateurs. And there have been some knock-down, drag-out fights. The cops -- by all accounts -- find themselves in deeper waters than they've ever experienced, and the city has been declared a state emergency to increase police presence. These reactionary gangs headed straight for confrontations with Black Lives Matter, who rightfully increased their general state of vigilance. One account says the thing began over anger at the upcoming removal of a statue of Robert E. Lee. Now it has spread over town

Will this happen more and more? I have no way of knowing, of who these people are, how they are organized, whether this is a blip or the beginning of a pattern. I know that probative masculinity traverses the political spectrum plotted from right to left. And boys want to prove their masculinity by fighting. The White Nationalists have hardly been subtle about their desire for war. The seek to be in a state of warfare, because they imagine this is how to get the gaze of approval from their idol -- masculinity. Lefty boys (and a few girls) fighting righty boys (and a few girls) is a win-win for fighty boys. Strike a pose. Having said this, the violent confrontations are picked up and amplified by media, giving an untrue impression about the overall character of the opposition.

I fear the reactions to these provocations nearly as much as I fear the provocations themselves. I pray that they are self-limiting, that we are still sufficient in numbers and moral will to dissolve them, like phagocytes. Because fight boys are drawn to conflict as much out of a desire for masculine esteem as by any real desire to defend. Incredibly narcissistic, yes, but there you have it. That impulse to prove oneself A Man . . . jumps right up in front of boys, from long training, and it is a wee bit Pavlovian.

Woof.

So maybe "Charlottesville" will become the first act in a continuing and progressively more dreadful play. Maybe we've passed some point of no return, and the worst is already in train. Maybe Donald Strangelove will disappear "Charlottesville" inside the mushroom clouds of tactical nuclear weapons.

Or maybe we will look back, in five years or ten, and remember "Charlottesville," the name of a memory with many interpreters, a cultural Rorschach test, freighted with bitter grief. The first act in a longer, sadder story. I pray it is not.

Enough! Damn!

These are fearful times. Donnie has discovered there are nukes in the closet, and he wants to boardgame with them in Korea. And his alter -- Kim Jong Un -- seems to be as possessed by masculine blustering as Agent Orange. Really, y'all. This is for-real pretty scary. And what's motivating the process right now is probative masculinity.

Charlottesville.

Apparently White Nationalists are rampaging through the city, confronting counter-protesters, some peaceful, some provocable, some likely themselves provocateurs. And there have been some knock-down, drag-out fights. The cops -- by all accounts -- find themselves in deeper waters than they've ever experienced, and the city has been declared a state emergency to increase police presence. These reactionary gangs headed straight for confrontations with Black Lives Matter, who rightfully increased their general state of vigilance. One account says the thing began over anger at the upcoming removal of a statue of Robert E. Lee. Now it has spread over town

Will this happen more and more? I have no way of knowing, of who these people are, how they are organized, whether this is a blip or the beginning of a pattern. I know that probative masculinity traverses the political spectrum plotted from right to left. And boys want to prove their masculinity by fighting. The White Nationalists have hardly been subtle about their desire for war. The seek to be in a state of warfare, because they imagine this is how to get the gaze of approval from their idol -- masculinity. Lefty boys (and a few girls) fighting righty boys (and a few girls) is a win-win for fighty boys. Strike a pose. Having said this, the violent confrontations are picked up and amplified by media, giving an untrue impression about the overall character of the opposition.

I fear the reactions to these provocations nearly as much as I fear the provocations themselves. I pray that they are self-limiting, that we are still sufficient in numbers and moral will to dissolve them, like phagocytes. Because fight boys are drawn to conflict as much out of a desire for masculine esteem as by any real desire to defend. Incredibly narcissistic, yes, but there you have it. That impulse to prove oneself A Man . . . jumps right up in front of boys, from long training, and it is a wee bit Pavlovian.

Woof.

So maybe "Charlottesville" will become the first act in a continuing and progressively more dreadful play. Maybe we've passed some point of no return, and the worst is already in train. Maybe Donald Strangelove will disappear "Charlottesville" inside the mushroom clouds of tactical nuclear weapons.

Or maybe we will look back, in five years or ten, and remember "Charlottesville," the name of a memory with many interpreters, a cultural Rorschach test, freighted with bitter grief. The first act in a longer, sadder story. I pray it is not.

Enough! Damn!

Monday, July 24, 2017

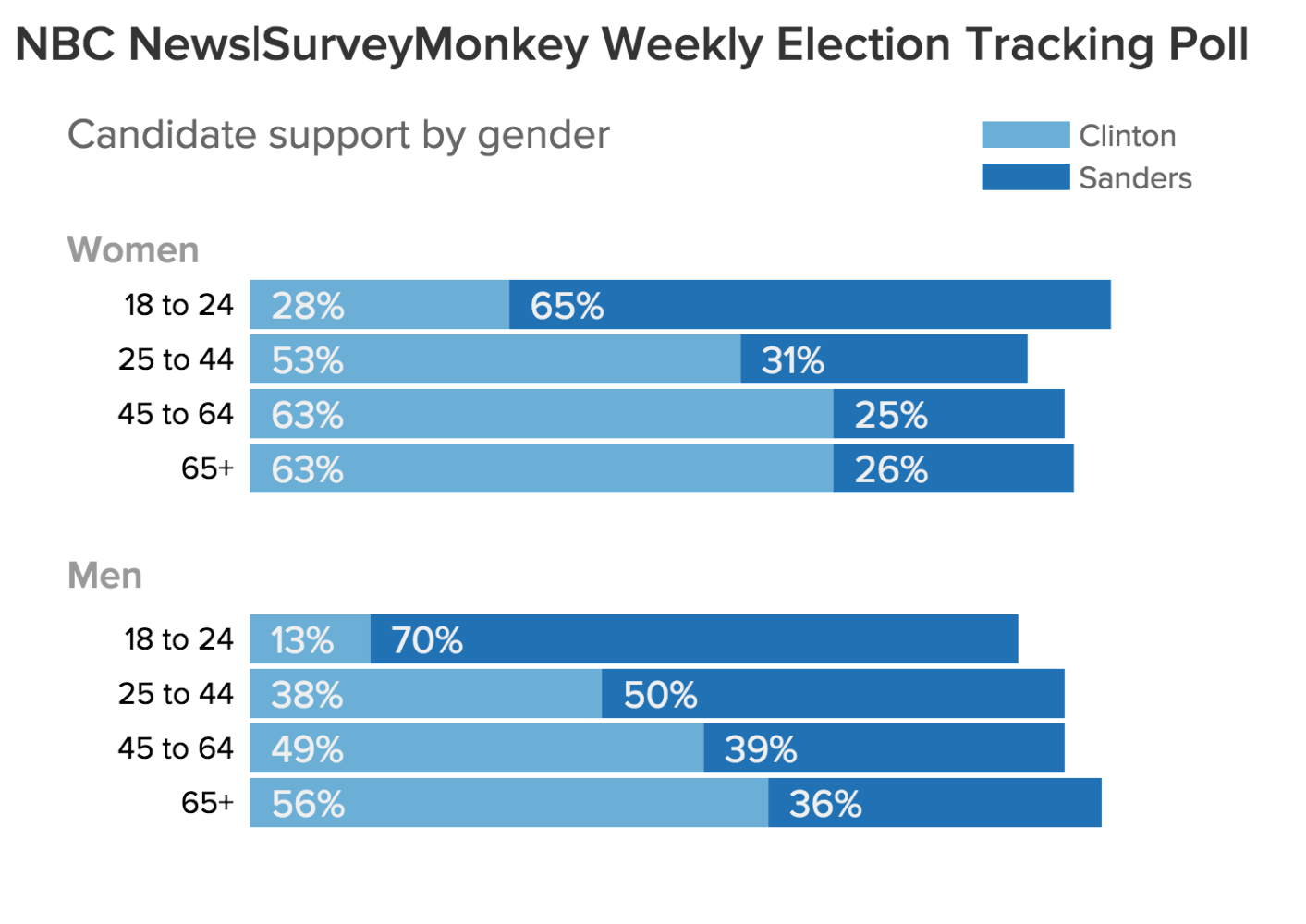

Demographics aiming at 2020

People vote, or they don't, if they can vote, and some can't, but when a lot of people vote, you can count what they do and at least see some trends.

Monday, July 17, 2017

Guns, guns, guns

. . . as the old Guess Who song went.

Reading about guns every day, and -- of course -- seeing them on TV and in films as instruments of redemption. The perennially armed cops in the US are already heading to fatal shootings in excess of one thousand before the end of 2017; and there is the development of the Redneck Revolutionary movement -- supposedly antifascist -- in which ostensibly antiracist white people remain rooted in, and celebrate, gun culture. "Racism no - Guns yes" is their mantra apparently.

American culture is Baudrillard on steroids and acid. The simulacra has taken over as we withdraw into our electronic life-support and hallucination dens. We come to believe that what we read and see in audiovisual media is true, in part because we have eschewed real experience as too troublesome or risky. We need a reality check on guns.

I was a gunfighter once. Really, I mean it. I was a member of the Army's "counterterrorist" direct action outfit in Ft. Bragg; and the main skill we developed for what were called "surgical operations" like hostage rescue, etc., was marksmanship and close-quarter (gun) battle (CQB). I worked both as an assaulter -- the guys who enter the room -- and a sniper -- the guys who cover the crisis site from without using precision rifles. We really learned our guns. As an assaulter, it was nothing to spend endless hours and thousands upon thousands of rounds of ammunition from our submachine guns and sidearms to achieve the high levels of accuracy required to enter a closed space with our comrades, hostages, and "bad guys," and to be confident that we could place our shots into a five inch circle in a fraction of a second. This practice took a great deal of time and it cost a great deal of money (not our money, but tax revenues). Way more time and money than most people have, even most people who have guns.

We thought about ammunition a great deal, especially how it passes through targets (terminal ballistics) and ricochets. Because, if you are supposed to be ready to rescue hostages, it kind of defeats the purpose if you shoot the "bad guy" and the bullet passes through him and enters the body of a rescu-ee. This was a special concern for aircraft hijacking scenarios, because everyone is lined up tightly in seats like human sardines. One's shooting sector is a long, linear tube.

We decided to test ammunition, and we spent a week testing it at an "aircraft graveyard" in the Arizona desert. Terminal ballistics were tested using gelatin blocks to simulate human bodies. We made gelatin blocks that were body-sized, gelatin blocks that were super-sized, and even gelatin blocks that were supplemented with ribs from a local butcher. We lined up the blocks in frames on aircraft seats, in frames that were lined up outside, and in frames that were separated by variable distances. And we shot them, again and again, photographing and recording data along the way.

We found that the most common pistol round (and our submachine gun rounds), the 9mm, when fired from various pistols, would pass through around three blocks and seat backs before coming to rest in the fourth gelatin block. Okay, this was not so good. Fortunately then, our own standard sidearms were souped-up M1911 45 calibers, that fired a fatter, slower round than the 9mm; and when we tested the 45s, they only went through one block, one seat back, and partway into the next block. Combining this subsonic round with careful shot placement (in split seconds) might at least minimize collateral damage. Shotguns were better the lighter the load, so the 00 buckshot that was our standard went into a second block, whereas the substitution of #6 or smaller "birdshot" kept the projectiles in the first block unless one was almost at point blank range.

Cops use 9mm ammunition for the most part. Assault rifles as long guns (usually 5.56mm or .223 caliber), and 00 buckshot in their shotguns (they also have "bean bag" loads for "riots"). Gun nuts like assault rifles and 9mm or other hot (supersonic) loads for their sidearms. NRA type gun nuts love to talk about the technics and ballistics; and they fantasize about killing home intruders, rescuing white damsels, fighting bad governments in the woods, and shooting black people, "Mexicans," and-or Muslims. Go to guns shows and shooting events, and they talk about this shit quite openly. Now we have the Redneck Revolutionaries, who may have different fantasy targets, but they are still mostly boys who can't relinquish the fantasy of proving their manhood by shooting "the bad men" (in the fantasies, the targets are mostly men, because killing men is more probative of masculinity than shooting women). Then they are caught in a camera angle from below, sun on their faces, wind blowing their hair, True Heroes.

Because they are fantasists and paranoids, gun nuts are looking for a fight; and the immediate possession of a gun, carrying that is, amplifies this pugnaciousness . . . a lot. The quest for masculinity is fundamentally predicated on (deep, unconscious, sexual) fear, and the possession of a firearm is not merely an antidote to fear; it generates that belligerent "courage" that can only originate from a deep, unconscious fear. So guns don't only make people physically more dangerous; they make people psychologically far more dangerous.

An armed society is not a polite society. An armed society is a dangerously stupid society. I'm not talking about hunters in Canada or Iceland who keep a deer rifle in the closet. I'm talking about the exploding mass of sexually-insecure white males who are carrying their Sig Sauers and Berettas into Walmarts and Krogers and middle schools to pick up their kids. At the most extreme, the Preppers -- Lord, have mercy, who are armed to the teeth even as they've lost their minds.

I've proposed elsewhere that Just War theories lost their raison d'etre with the advent of modern war, in no small part because automatic weapons, cannon fire, and bombs of all sorts cannot distinguish friend from foe, and even were they able to, their impact areas/bursting radii are too large to use these weapons without accepting in advance that they will kill bystanders. And soldiers inevitably kill civilians on purpose; but we'll stay with bystander casualties.

In World War I, 7 million combatants died alongside 6.6 million civilians. Fatality counts exclude the even larger numbers of combatants and civilians who are injured, often in ways that cause permanent suffering and disability. In World War II, some 70 million died, and even excluding the ethnic cleansing campaigns, bystander deaths outnumbered combatant deaths by nearly three to one. Sixty-seven percent of Korean War casualties were civilians, and with Allied operations against the North, North Korea lost fully twenty percent of its total population. Around 2 million Vietnamese civilians were killed during the US invasion and occupation, compared to around half that number in combatants. Four out of every five casualties in Afghanistan since 2001 have been civilians; and two of every three casualties in Iraq since the 2003 invasion have been non-combatants. Drone strikes, which are called "surgical," kill ten non-combatants for every combatant -- if you believe the remote operators can really distinguish such a thing through a flying camera. So there's my point, in brief, about "just" war.

My point about guns is similar, if on a smaller scale. Modern rifled firearms and, at close range, shoguns have been refined toward a telos of ever-increasing efficacy -- and by efficacy, we mean lethality at various ranges. They are designed for the instant destruction of tissue sufficient to cause death.

In 2011, there were around 34,000 fatalities from firearms and around 74,000 non-fatal injuries in the US. We use guns in 67 percent of homicides, 50 percent of suicides, 43 percent of robberies, and 21 percent of aggravated assaults. I myself survived eight conflict areas in the Army without sustaining a gunshot wound, and was finally shot outside a bar in 1991 in Hot Springs, Arkansas. These statistics can be deceiving, because when we compare homicides with suicides, the percentages lie.

We kill ourselves more often than we kill others here, and 60 percent of suicides use firearms. Suicides account for 65 percent of suicide deaths -- in part because the shooting is more accurate, and in part because successful suicides, while the numbers compared to attempts are unknown, have a high correspondence to the method used. Firearms, at above 80 percent as far as we know, are the absolute most successful method. So, all other things being equal, a firearm in the house dramatically increases the odds that it will be used for some confused, sick, broken, humiliated, and-or lonely person to extinguish themselves. In 2013, 41,149 were successful -- men far more than women, because men choose firearms, naturally. By comparison, just over a thousand home invasions were repelled by the threat of a firearm, and actual burglary-homicides in the US are around 100 a year nationwide. Do the math. You are quite a bit more likely to have a suicidal person among family or friends in the house than a lethal burglar.

Or kids. We kill more kids per capita with guns than any country in the world, and around 320 kids are snuffed out each year here in home gun accidents, more than three times the probability of repelling an actual homicidal intruder with a gun. (Not to forget, if your home is intruded upon by a killer -- which is about twice as likely as being killed by lightning -- the best course of action is to leave and call 911. Burglars look for guns, because they have a great resale value.)

All that aside now, however, let's get down to the creepy business of what exactly gunshots do. A contained explosion sends missiles down a barrel at speeds that can go through the average elm tree. When a bullet hits a body, it doesn't simply punch a hole and slice through a tiny column of skin, organ tissue, bone, etc. At high velocity, projectiles have brand new physical properties. Three of the immediate outcomes are in-flight deviation, distortion of the projectile, and cavitation. The projectile begins responding to its environment as soon as it leaves the barrel -- so it might tail-drop ("yaw"), or wobble, or turn. The projectile is distorted by the impact with material (like the flesh and bone of a human being) and loses its sleek, perfect cylindricality. The projectile pushes a shock wave through the air around its flight path which enters the body and tears through the tissues surrounding the bullet path in a millisecond "cavity," leaving behind extensive damage not only along the path, but through tissues distal to the path. That's why entry wounds can be quite small, but exit wounds can look like bomb craters in meat. If it hits the upper arm, for example, it might break the bone without ever touching is, or tear up the brachial artery (fatal), or destroy large amounts of muscle tissue (resulting in shock, future infections, permanent disability). A small caliber, subsonic round like a 22 might leave the gun your three-year-old has found, enter the head of your eight-year-old, then ricochet around inside the skull until all its kinetic energy is gone. In a nanosecond. No do-overs.

All this is true if you've just shot Hannibal Lecter; but it is equally true if you missed old Hannibal and the bullet passed through a sheetrock wall and hit the lawyer Hannibal has tied up in the next room for tonight's dinner. Or you may shoot at that fourteen-year-old heroin-addicted home intruder, miss the bad child, have the bullet strike your stone veneer, ricochet, and end up in the lumbar spine of your niece whose come to visit and sleeps in the spare bedroom. If you fire ten times, maybe you can hit the bad child, too, and punish the kid-burglary by blowing holes in his skull and abdomen. That should make you feel better.

By the way, they don't show this kind of stuff in TV dramas and boyflix.

Even if you are a crack shot at the range where you hang out with your buddies and talk about how you'll "double-tap" the bad guys, when something actually happens that provokes you to draw your weapon (instead of the smart thing to do when there is danger, which is to haul ass out of there . . . but the gun has made you stupid as shit now), another person will not be standing still like a target in good light with a range master to ensure no one is downrange when you fire. You cannot, not under any circumstances, guarantee that you will not miss, that you will not hit a bystander, that you will not overreact. And for that reason, NO ONE should be allowed to carry firearms around with them, because they are already, knowingly or not, accepted that they might shoot someone unintentionally. I include cops in this calculus. Why are cops so brave in other countries that they can walk around unarmed except for a baton, some Mace, and maybe a hand taser?

Anyone who calls oneself a Christian and carries a firearm -- given what I just pointed out about our absolute inability to control outcomes in the employment of firearms -- ought to be ashamed and turn in your credentials. You cannot follow Jesus with a Glock in your belt. I'm sorry. Just not possible.

No matter what cockamamie scenario you construct to justify carrying a gun (not talking about someone hunting) for "protection," you cannot escape the reality of this inability to control what happens when a firearm is used, because you cannot predict the circumstances of its use.

You penises will not fall off when you refuse to carry. And you are far less likely to have that unpredictable instant that saddles you with a lifetime of regret.

Reading about guns every day, and -- of course -- seeing them on TV and in films as instruments of redemption. The perennially armed cops in the US are already heading to fatal shootings in excess of one thousand before the end of 2017; and there is the development of the Redneck Revolutionary movement -- supposedly antifascist -- in which ostensibly antiracist white people remain rooted in, and celebrate, gun culture. "Racism no - Guns yes" is their mantra apparently.

American culture is Baudrillard on steroids and acid. The simulacra has taken over as we withdraw into our electronic life-support and hallucination dens. We come to believe that what we read and see in audiovisual media is true, in part because we have eschewed real experience as too troublesome or risky. We need a reality check on guns.

I was a gunfighter once. Really, I mean it. I was a member of the Army's "counterterrorist" direct action outfit in Ft. Bragg; and the main skill we developed for what were called "surgical operations" like hostage rescue, etc., was marksmanship and close-quarter (gun) battle (CQB). I worked both as an assaulter -- the guys who enter the room -- and a sniper -- the guys who cover the crisis site from without using precision rifles. We really learned our guns. As an assaulter, it was nothing to spend endless hours and thousands upon thousands of rounds of ammunition from our submachine guns and sidearms to achieve the high levels of accuracy required to enter a closed space with our comrades, hostages, and "bad guys," and to be confident that we could place our shots into a five inch circle in a fraction of a second. This practice took a great deal of time and it cost a great deal of money (not our money, but tax revenues). Way more time and money than most people have, even most people who have guns.

We thought about ammunition a great deal, especially how it passes through targets (terminal ballistics) and ricochets. Because, if you are supposed to be ready to rescue hostages, it kind of defeats the purpose if you shoot the "bad guy" and the bullet passes through him and enters the body of a rescu-ee. This was a special concern for aircraft hijacking scenarios, because everyone is lined up tightly in seats like human sardines. One's shooting sector is a long, linear tube.

We decided to test ammunition, and we spent a week testing it at an "aircraft graveyard" in the Arizona desert. Terminal ballistics were tested using gelatin blocks to simulate human bodies. We made gelatin blocks that were body-sized, gelatin blocks that were super-sized, and even gelatin blocks that were supplemented with ribs from a local butcher. We lined up the blocks in frames on aircraft seats, in frames that were lined up outside, and in frames that were separated by variable distances. And we shot them, again and again, photographing and recording data along the way.

We found that the most common pistol round (and our submachine gun rounds), the 9mm, when fired from various pistols, would pass through around three blocks and seat backs before coming to rest in the fourth gelatin block. Okay, this was not so good. Fortunately then, our own standard sidearms were souped-up M1911 45 calibers, that fired a fatter, slower round than the 9mm; and when we tested the 45s, they only went through one block, one seat back, and partway into the next block. Combining this subsonic round with careful shot placement (in split seconds) might at least minimize collateral damage. Shotguns were better the lighter the load, so the 00 buckshot that was our standard went into a second block, whereas the substitution of #6 or smaller "birdshot" kept the projectiles in the first block unless one was almost at point blank range.

Cops use 9mm ammunition for the most part. Assault rifles as long guns (usually 5.56mm or .223 caliber), and 00 buckshot in their shotguns (they also have "bean bag" loads for "riots"). Gun nuts like assault rifles and 9mm or other hot (supersonic) loads for their sidearms. NRA type gun nuts love to talk about the technics and ballistics; and they fantasize about killing home intruders, rescuing white damsels, fighting bad governments in the woods, and shooting black people, "Mexicans," and-or Muslims. Go to guns shows and shooting events, and they talk about this shit quite openly. Now we have the Redneck Revolutionaries, who may have different fantasy targets, but they are still mostly boys who can't relinquish the fantasy of proving their manhood by shooting "the bad men" (in the fantasies, the targets are mostly men, because killing men is more probative of masculinity than shooting women). Then they are caught in a camera angle from below, sun on their faces, wind blowing their hair, True Heroes.

Because they are fantasists and paranoids, gun nuts are looking for a fight; and the immediate possession of a gun, carrying that is, amplifies this pugnaciousness . . . a lot. The quest for masculinity is fundamentally predicated on (deep, unconscious, sexual) fear, and the possession of a firearm is not merely an antidote to fear; it generates that belligerent "courage" that can only originate from a deep, unconscious fear. So guns don't only make people physically more dangerous; they make people psychologically far more dangerous.

An armed society is not a polite society. An armed society is a dangerously stupid society. I'm not talking about hunters in Canada or Iceland who keep a deer rifle in the closet. I'm talking about the exploding mass of sexually-insecure white males who are carrying their Sig Sauers and Berettas into Walmarts and Krogers and middle schools to pick up their kids. At the most extreme, the Preppers -- Lord, have mercy, who are armed to the teeth even as they've lost their minds.

I've proposed elsewhere that Just War theories lost their raison d'etre with the advent of modern war, in no small part because automatic weapons, cannon fire, and bombs of all sorts cannot distinguish friend from foe, and even were they able to, their impact areas/bursting radii are too large to use these weapons without accepting in advance that they will kill bystanders. And soldiers inevitably kill civilians on purpose; but we'll stay with bystander casualties.

In World War I, 7 million combatants died alongside 6.6 million civilians. Fatality counts exclude the even larger numbers of combatants and civilians who are injured, often in ways that cause permanent suffering and disability. In World War II, some 70 million died, and even excluding the ethnic cleansing campaigns, bystander deaths outnumbered combatant deaths by nearly three to one. Sixty-seven percent of Korean War casualties were civilians, and with Allied operations against the North, North Korea lost fully twenty percent of its total population. Around 2 million Vietnamese civilians were killed during the US invasion and occupation, compared to around half that number in combatants. Four out of every five casualties in Afghanistan since 2001 have been civilians; and two of every three casualties in Iraq since the 2003 invasion have been non-combatants. Drone strikes, which are called "surgical," kill ten non-combatants for every combatant -- if you believe the remote operators can really distinguish such a thing through a flying camera. So there's my point, in brief, about "just" war.

My point about guns is similar, if on a smaller scale. Modern rifled firearms and, at close range, shoguns have been refined toward a telos of ever-increasing efficacy -- and by efficacy, we mean lethality at various ranges. They are designed for the instant destruction of tissue sufficient to cause death.

In 2011, there were around 34,000 fatalities from firearms and around 74,000 non-fatal injuries in the US. We use guns in 67 percent of homicides, 50 percent of suicides, 43 percent of robberies, and 21 percent of aggravated assaults. I myself survived eight conflict areas in the Army without sustaining a gunshot wound, and was finally shot outside a bar in 1991 in Hot Springs, Arkansas. These statistics can be deceiving, because when we compare homicides with suicides, the percentages lie.

We kill ourselves more often than we kill others here, and 60 percent of suicides use firearms. Suicides account for 65 percent of suicide deaths -- in part because the shooting is more accurate, and in part because successful suicides, while the numbers compared to attempts are unknown, have a high correspondence to the method used. Firearms, at above 80 percent as far as we know, are the absolute most successful method. So, all other things being equal, a firearm in the house dramatically increases the odds that it will be used for some confused, sick, broken, humiliated, and-or lonely person to extinguish themselves. In 2013, 41,149 were successful -- men far more than women, because men choose firearms, naturally. By comparison, just over a thousand home invasions were repelled by the threat of a firearm, and actual burglary-homicides in the US are around 100 a year nationwide. Do the math. You are quite a bit more likely to have a suicidal person among family or friends in the house than a lethal burglar.

Or kids. We kill more kids per capita with guns than any country in the world, and around 320 kids are snuffed out each year here in home gun accidents, more than three times the probability of repelling an actual homicidal intruder with a gun. (Not to forget, if your home is intruded upon by a killer -- which is about twice as likely as being killed by lightning -- the best course of action is to leave and call 911. Burglars look for guns, because they have a great resale value.)

All that aside now, however, let's get down to the creepy business of what exactly gunshots do. A contained explosion sends missiles down a barrel at speeds that can go through the average elm tree. When a bullet hits a body, it doesn't simply punch a hole and slice through a tiny column of skin, organ tissue, bone, etc. At high velocity, projectiles have brand new physical properties. Three of the immediate outcomes are in-flight deviation, distortion of the projectile, and cavitation. The projectile begins responding to its environment as soon as it leaves the barrel -- so it might tail-drop ("yaw"), or wobble, or turn. The projectile is distorted by the impact with material (like the flesh and bone of a human being) and loses its sleek, perfect cylindricality. The projectile pushes a shock wave through the air around its flight path which enters the body and tears through the tissues surrounding the bullet path in a millisecond "cavity," leaving behind extensive damage not only along the path, but through tissues distal to the path. That's why entry wounds can be quite small, but exit wounds can look like bomb craters in meat. If it hits the upper arm, for example, it might break the bone without ever touching is, or tear up the brachial artery (fatal), or destroy large amounts of muscle tissue (resulting in shock, future infections, permanent disability). A small caliber, subsonic round like a 22 might leave the gun your three-year-old has found, enter the head of your eight-year-old, then ricochet around inside the skull until all its kinetic energy is gone. In a nanosecond. No do-overs.

All this is true if you've just shot Hannibal Lecter; but it is equally true if you missed old Hannibal and the bullet passed through a sheetrock wall and hit the lawyer Hannibal has tied up in the next room for tonight's dinner. Or you may shoot at that fourteen-year-old heroin-addicted home intruder, miss the bad child, have the bullet strike your stone veneer, ricochet, and end up in the lumbar spine of your niece whose come to visit and sleeps in the spare bedroom. If you fire ten times, maybe you can hit the bad child, too, and punish the kid-burglary by blowing holes in his skull and abdomen. That should make you feel better.

By the way, they don't show this kind of stuff in TV dramas and boyflix.

Even if you are a crack shot at the range where you hang out with your buddies and talk about how you'll "double-tap" the bad guys, when something actually happens that provokes you to draw your weapon (instead of the smart thing to do when there is danger, which is to haul ass out of there . . . but the gun has made you stupid as shit now), another person will not be standing still like a target in good light with a range master to ensure no one is downrange when you fire. You cannot, not under any circumstances, guarantee that you will not miss, that you will not hit a bystander, that you will not overreact. And for that reason, NO ONE should be allowed to carry firearms around with them, because they are already, knowingly or not, accepted that they might shoot someone unintentionally. I include cops in this calculus. Why are cops so brave in other countries that they can walk around unarmed except for a baton, some Mace, and maybe a hand taser?

Anyone who calls oneself a Christian and carries a firearm -- given what I just pointed out about our absolute inability to control outcomes in the employment of firearms -- ought to be ashamed and turn in your credentials. You cannot follow Jesus with a Glock in your belt. I'm sorry. Just not possible.

No matter what cockamamie scenario you construct to justify carrying a gun (not talking about someone hunting) for "protection," you cannot escape the reality of this inability to control what happens when a firearm is used, because you cannot predict the circumstances of its use.

You penises will not fall off when you refuse to carry. And you are far less likely to have that unpredictable instant that saddles you with a lifetime of regret.

Sunday, July 9, 2017

Veteran Entitlements

Universities, like many institutions, are, beneath their

orderly veneer, sites of constant low intensity warfare. More so, perhaps,

because they deal in ideas, and human beings are correctively ordered in practical pursuits by the immovable

necessities of particular practices; but ideas are inflected by personal

psychology and a plurality of ideological commitments, neither of which is

anchored by practical necessity. I garden and fish, for example, and if I don’t

use the right soil and amendments or the right bait and technique, I get practical

feedback in the form of failure. But we can cling to many faulty, even bizarre,

ideas for quite some time, especially in universities, because some of these ideas

are never tested except within the framework of other ideas; and in a

pluralistic culture like ours, we have generated multiple frameworks with

premises that are so incommensurable with one another that—in the absence of

any ultimate authority for appeal—no resolution to conflicts is even possible.

And so the low intensity warfare in universities takes the form of sniping

through various media, character assassination, and the mobilization of cliques.

I know two people, whose names and institution I will not

cite, one of whom is engaging in this form of warfare against another over the

subject of military veterans. I’ll call them (androgynously) Pat and Gale. Pat

is a graduate fellow and a veteran, who has organized a group of veterans on campus.

Gale is an Ethics professor, never in the military, who is active in the

opposition to drone warfare and torture. Both claim to be opposed to war, their

pacifism rooted in Christian faith. Pat has had issues with Gale for quite some

time, based on Pat’s belief that non-veterans can never speak of veterans, and

Pat’s further belief that veterans are the only people who can speak with

enough authority on the topics of war and peace to “lead” these public

conversations. Gale disagrees. Recently Pat took one of Gale’s tweets from a

conference on war out of context, and made the claim that Gale was guilty of “cultural

appropriating” veterans.

The Gale tweet: “There is a gnosis of violence going on . .

. The notion that combat vets ‘know’ is not good for vets.”

Context: Gnosticism is an insider term among Christians (like

myself) that applies to a particular heresy which claims that redemption is

achieved by acquiring ever more esoteric (“higher”) forms of “knowledge” which progressively

liberate the divine spark. So what Gale tweeted might be translated as: There

is an idea that being a former combat soldier is the highest form of knowledge

about war; and this mistaken notion is not helpful for the actual human beings

who happen to be military veterans (most of whom, by the way, are not “combat”

vets). What they need is what the rest of us need: jobs, decent housing, health

care, maybe some education and training, and—from my own perspective—some life

skills that help them break a lot of military habits and a dependence on

veteran-esteem.

The tortured argument that Pat published in a university

veteran blog (mobilizing Pat’s clique) can be summarized as “veterans

constitute a culture, a culture that is equivalent to that of, say, African

Americans; and this tweet is an attempt to ‘appropriate’ the ‘voice’ of veterans,

so it is an instance of cultural appropriation.” Which is absurd. I’m sorry, it

just is. And it is a completely uncharitable misreading of what Gale was tweeting about.

But I’ve had this conversation with Pat myself, on more than

one occasion, and it needs a little background. Not the conversation about “cultural

appropriation,” per se, but the one

where veterans are some uniquely oppressed class of people, which Pat claims,

and with which I emphatically—as another veteran—disagree. If anything, what is

being appropriated in all this is the history of genuine oppression by a

uniquely entitled class of people—which we veterans are—and in this case by a

white veteran (Pat is white). Somehow, Pat claims, this tweet is “the standard pacifist justification of credibility

regarding any event about ‘war’ which invites participation by academic[s],’ whose expertise

derives exclusively from having ‘written about’ a subject with which they have

no ‘first hand’ experience.” As in conversations I have had with Pat

myself, for a pacifist, he has never had a good word to say about other

pacifists. Pat’s first hand experience in Iraq was in the Artillery branch, and

we’ll come back to why that is important.

Pat honestly believes that

being a veteran, whatever kind of veteran, who served in a conflict theater, in

whatever capacity, is the distinctive qualification for “leading” (he uses this

term) any discussion of war. In our own conversations, Pat explained to me that

he still missed and admired the camaraderie and shared hardships of military

life; and he has taken a page from Alasdair MacIntyre’s most ill-advised passing

reference to the military as a site of distinctively Aristotelian virtue—the military

as a polis, governed by particular

ideas of honor and integrity. He misses that cohesiveness, and believes that

this is the salvageable kernel of value that can be rescued from the uglier

business of what the American military is actually organized to do. Pat

actually teaches a class called “Virtues of War.” I reminded him during our

conversation about this that this is the experience of many kinds of collective

living, not just the military, but—for example—monastic life, women’s land,

firefighters, communes, earlier societies, and so forth.

This is a little like saying that the only people who are

qualified to speak about capitalism are production line workers, because they

are at that point where the rubber meets the proverbial road. It’s a preposterous

notion on its face, and a bald attempt to humiliate, marginalize, and silence

anyone who questions the somehow-exclusive authority of veterans to speak about

war.

How is the “first hand” experience of an Artillery soldier

the same—apart from the greater institutional culture that prevails prior to

the initiation of hostilities—as that of an infantry soldier or military police

prison guard or an office-bound intelligence analyst or a personnel clerk or a vehicle

mechanic or a hospital worker? Do people seriously believe that there is one

homogenous “first hand” experience of War, even among one set of imperial soldiers

in one theater, apart from General Orders, rank structure, and grotesque

ignorance of the people they occupy and attempt to control? Can the abused wife

of a soldier who has been formed by the (violently misogynistic) culture of the

military speak on war? Can the historian speak on war? When I was in Vietnam as

a nineteen-year-old, drug-addled grunt, was I more qualified to speak about the

causes of the war than some (ick) academic who had studied the history of the

conflict but eschewed participation? What about the people who are occupied, bullied,

wounded, and killed by soldiers? What about the people who make the weapons?

You see how perfectly imperfect this generalization of “the first hand

experience of war” is, when you begin to appreciate how complex and

far-reaching is the phenomenon of war itself.

Are we talking about danger? About the risks of service

giving someone a special claim to authority? If so, then before we list

veterans, we need to list loggers, fisherman, and power line workers who die

with greater frequency than soldiers, even during the last decade and a half of

high-intensity military occupations. Roofers die at the same rate as the

military (even when you include military suicides, which are more common among

non-combatant soldiers and veterans that combatants), and for a lot lower pay.

But we don’t see Roofers Day parades or statues of fallen power line workers, or bridges named after loggers and fishermen. In terms of job-related disability, home health workers

are far worse off than military veterans. And even in the military, there is a

hierarchy of risk. Explosives Ordinance Disposal (EOD) is the best job per

capita for being killed at work, followed by Special Operations, combat medic,

supply truck driver (since Iraq, when our war victims learned to use mechanical

ambushes), infantry, rescue swimmer, and helicopter pilot. Does this mean that EOD

is the best-qualified to speak about war, even if the technician has no clue

about how he or she ended up in Iraq or Afghanistan or Syria?

Am I allowed to say, as a veteran, just how full of shit

many veterans are? Or what kinds of scuttlebutt makes its way through military

barracks? Or how many, and often ridiculous, ways the “first hand” experience

of veterans in conflict areas is interpreted by the participants? Or how many

Wrong Beliefs these kids have about what they are doing, why they are doing it,

and who they are doing it to?

At the full-of-shit desk, standing tall at the front of the

line, is PTSD! While there are a few people who suffer from post-traumatic

stress in ways that create debilitating problems in their lives, including

people who are not veterans, you can’t throw a rock nowadays without hitting

some vet who claims the disability (and a bumper crop of shrinks willing to

make the diagnosis for disability claims). It is almost a status symbol, yielding

simultaneous sympathy and admiration for the mentally-wounded “hero,” and . . .

oh, by the way, gives anyone a ready excuse for being a world-class shit. I’m

disrespectful to women . . . PTSD. I beat my kids and spouse . . . PTSD. I’m a

loud-mouth drunk . . . PTSD. I’m a rapist . . . PTSD. I’m a lazy slug . . .

PTSD. I’m a bully . . . PTSD. I committed armed robbery . . . PTSD. You get

sympathy, admiration, and a get-out-of-jail-free card. What’s the downside?

So what connects this posing/malingering by veterans, the

faulty claim that veterans have some exclusive authority to speak about war, the

nostalgia many veterans feel for their days in uniform, and the way veterans get

special recognition, official and unofficial, for their “sacrifices” (the

military is the highest-paying, highest-benefits job available to most

high-school graduates who qualify)?

C’mon, let’s just say it. Militaristic American nationalism.

And veterans, while they do get the shitty end of the stick on some benefits

(like everyone else in neoliberal, downsizing society), get to cash in on the

status and esteem. I wish fishermen and home health workers got the same deal I

have—as a retired army veteran—for health insurance. And why aren’t roofers

held in such high esteem? They don’t kill anyone or destroy property or spread

pain and grief and devastation in their wake. They do work that keeps us dry

and comfortable. I have been made to sit in a docked plane and wait while those

in uniform were allowed to disembark before the other passengers, and once one

jingo jughead started clapping for the kids in uniform, everyone else felt

obliged to join in (when I didn’t, people looked at me like I just came out of

Fido’s ass).

Pat, going back to our story, supports his claim of cultural

appropriation/oppressed class by noting that “veteran” is a federally protected

status, like women in sports or black people who want to vote or gay folk who

want a job. Really? Veterans need special protection? In fact, what this status

is another perquisite that sets aside

jobs and other benefits specifically for veterans. Anyone ever seen a law that

requires that X percent of your contracting work force be lesbians?

This may at first blush seem strange that I am myself

speaking as a veteran—kind of, everything I am saying is equally valid whoever

says it—but I am not saying veterans ought not to speak of war, peace, et al, only that we should be held to

the same standards as everyone else and not be allowed to get away with talking

out of our asses. Our experiences, while always filtered through many personal

and historical lenses, are important. But the question is, How are they

important? My take is, what we say is important, if what we say is true, as

correctives.

One of the reasons veterans are worshipped in this

militaristic culture is the mystique that surrounds the military, and this

mystique includes a boatload of silly misapprehensions created by military

propaganda, official and unofficial, as well as silly macho stories in books,

television, and film. The collective imagination of the military by those who

are not in the military is one of heroic martial sacrifice, while life in the

actual military is—99.9 percent of the time—bureaucratic piddling and checklisting,

day-to-day drudgery, and many eyes on many clocks waiting to get home and pop

that first beer. Speaking of which, American military home-life is often an

orgy of consumerism. Military towns are now oases of wealth accumulation, where

tens of thousands of young people with well-paying, secure jobs make money rain

on restaurants and bars and lenders and toymakers (adult and child) and

entertainers and the builders of cheap new houses.

Veterans benefit from this mystique, and so there is a tacit

understanding to keep mum about how off the mark it really is.

Susan Jeffords once wrote about “the war story,” that story

of the pathos of one or a few people (usually men) that serves as an “ideological

transmission belt” in support of war, by taking the focus off the geopolitical,

the financial, the structural reasons for wars, and forcing us to identify with

the individual “warrior.” This is precisely what is attempted through the

insistence on the veteran as the ultimate authority on war. If correction is

what veterans can offer to any discussion of war, then the corrections cannot

be more war stories unless the goal is to valorize the warrior and the war.

When I say corrections, I mean just that. Correcting errors.

When someone says the US was protecting the South Vietnamese from aggression, I

can say that the grunts in my unit were encouraged to hate the Vietnamese—all of

them—and to seek any excuse we could find to kill as many of them as we could.

I can say that when I spoke with other grunts from other units, they said the

same thing. When someone calls a battalion a squad, or treats such terms as

interchangeable, or calls all soldiers officers, or doesn’t know the difference

between Special Operations and Special Forces, etc., then I can offer

corrections. In Pat’s case, Pat wrote an article (as a former artillery

soldier) describing snipers as people who kill from several kilometers away, making

them like artillerymen, I can offer a correction. I was a sniper for a time,

and even the trainer for 2nd Battalion, 7th Special

Forces’ sniper. Snipers generally shoot at ranges under 800 meters, more often

half that, and they see what they shoot (one person), unlike artillery which

shoots across the horizon with shells that have bursting radii that can kill

many unseen people. You see how

easily even a veteran can write about combat experience and say things that are

mistaken.

Is there such a thing as military culture? I suppose there is,

but it also consists of many subcultures. The overall culture is expressed in

the language and norms (legal, policy, custom). In Basic Training or Boot Camp,

everyone learns how to tell time by a 24-hour clock, express distance using the

metric system, know the rank system, follow drill commands, comply with customs

and courtesies, basic marksmanship, and so on. After that, people are trained

as one form of specialist or another, with further subdivision among

specialties by rank. But there is also an unofficial culture, one that is

oriented by woman-hating machismo, careerism, and a love of violence. Hey, most

young men don’t join the Army or Marines thinking, “Gosh oh gee, I want to

serve my nation.” Most, when you talk with them, say either “I need money for

school” or “I wanna kill people and blow shit up.”

If there is an official virtue that is reinforced in

practice in the military, it is authoritarianism coupled with unquestioning

obedience. Ethically, the military is absolutely consequentialist. Mission

accomplishment is supreme, and all other factors are subordinated to it. You

know what? Gangs and organized crime syndicates have camaraderie and

cohesiveness, too. Sometimes, we just have to leave the comfort of what we know.

Veterans are not superior in any sense

to non-veterans. We are simply veterans; and if we have certain practical

concerns in common (VA benefits, e.g.)

or certain social concerns in common (the opposition to war), we can join

together. Veterans For Peace and Iraq Veterans Against the War have done that

(though many in those organizations still cling to the “special” status of being

veterans, instead of simply serving as corrective witnesses.

Elevating the “voices of veterans” (Jeffords’ “war stories”)

and claiming special authority for “veterans” is a fundamentally reactionary

endeavor; and it will, unchecked, lead one (Pat?) to eventually embrace a

reactionary position on the subject of war (and the abandonment of any

semblance of pacifism). Because there is a contradiction at the heart of this

relation between universally valorizing the soldier/veteran and opposing war.

The veteran-as-hero, as well as the veteran-as-victim, and the

veteran-as-gnostic-knower, all fall on the side of military nationalism. The

veteran is most well-served, as is anyone, when served as the particular and whole person he or she is, not as a “protected”

or hyper-valorized category. Because the category itself is too general to be useful

except in the service of nationalism

and war.

Friday, May 12, 2017

Semiotic

Why Semiotics?

Richard

Dawkins is among those who propose something called universal Darwinism, which purports first of all that mathematically

demonstrable scientific discovery constitutes an ultimate truth claim; that is,

it can explain everything. Everything. Universal

Darwinists, however, violate their own stated principle by jumping to the

non-mathematically-demonstrable conclusion that both nature and society can be

explained using nothing but their “Darwinist” triad, i.e., adaptation (evolution) through variation,

selection of the “fit,” and retention

(through heredity).[1]

They have taken an overly general account of natural selection and attempted a

further generalization of that account to everything else: economics,

psychology, anthropology, and linguistics. Linguistics, for our discussion,

falls within the scope of semiotics—the

study of signs—and we will show why universal

Darwinism is inadequate to the task of understanding any of these things.

The linguistics—or study of language—of

the universal Darwinists, whose

obsessive motivating purpose seems to be proving a negative—that there is no

God[2]—is called, unsurprisingly,

“evolutionary linguistics.” In evolutionary linguistics, the basic assumption

is that a word or phrase, for example, is selected in the same way that nature

selects for long necks on giraffes, through a process of variation (different

lengths of neck), selection of the “fit” (longer necks get more food and live

longer to reproduce more); and retention (the trait is stored genetically and

passed on through reproduction of the “fit”).[3]

What is assumed in this worldview is a

clockwork materialism, or the

assumption of the material as an account of all

being, including human culture. This is an aspect of the dualism we discussed

earlier. The subject is unreliable, but the object contains the only

discernable truth, discoverable

through strict observation that is disciplined with mathematics. The Austrian

philosopher Rudolf Steiner (1865—1925) explained how this was an attempt to

break being into time and space

(instead of time-space), separate them and making space the dominant partner.

The concept of matter arose only because of a very misguided concept of time. The general belief is that the world would evaporate into a mere apparition without being if we did not anchor the totality of fleeting events in a permanent, immutable reality that endures in time while its various individual configurations change. But time is not a container within which changes occur. Time does not exist before things or outside of them. It is the tangible expression of the fact that events—because of their specific nature—form sequential interrelationships.[4]

For Darwin, as well as Newton, whose

mechanical ideas Darwin adopted, and for Dawkins with his posse of God-phobic

materialists, the separation of time and space, and time’s subordination to

space (materiality that “holds still” for observation), were necessary to

reduce all reality to a sequence of simple, mechanical causes-and-effects, what

Aristotle called “efficient causation.”[5] The other three types of

causation (see footnote) made them dizzy. The reduction of all phenomena to

efficient causes is an attempt at control

(an obsession most often associated with anxiety). If time is not a thing but

an expression of shifting relations, then it, too, is wild. It needs to be

domesticated by the material, locked into plots on a map. French philosopher

Henri Bergson (1859–1941), who analyzed the phenomenon of cinema, compared this

attempt by materialists, to domesticate time, to films—which, though they

appear to flow continuously, can be broken down into frames where all that

disorienting motion can be frozen into the apparent three dimensions of space—height, width, depth—an illusion

cast on a two-dimensional surface.

Such is the contrivance of the cinematograph. And such is also that of our knowledge. Instead of attaching ourselves to the inner becoming of things, we place ourselves outside them in order to recompose their becoming artificially. We take snapshots, as it were, of the passing reality . . . We may therefore sum up . . . that the mechanism of our ordinary knowledge is of a cinematographical kind.[6]

This materialist

notion of language, then, not only cannot account for Taussig’s Bolivian

peasant-miners baptizing money, it cannot account for the immense complexity of

a simple conversation between two Western metropolitan persons about a novel

they both read. What is required is an expansive

and inclusive, not a reductive and

exclusive, approach to language that allows for context. When Ludwig

Wittgenstein (1889—1951) formulated his ideas about language, which he compared

to games, he pointed out that language can mean “giving orders, and obeying

them, describing the appearance of an object, or giving its measurements, constructing

an object from a description (a drawing), reporting an event, speculating about

an event, forming and testing a hypothesis, presenting the results of an

experiment in tables and diagrams, making up a story; and reading it, play-acting,

singing, guessing riddles, making a joke or telling it, solving a problem in

practical arithmetic, translating from one language into another, asking,

thinking, cursing, greeting, and praying.”[7]

The universal

Darwinists, in trying to break everything in the universe down to its

evolutionary utility, evade these

problems by claiming that they simply haven’t yet identified the whole train of

cause-and-effect. In other words, their theory is correct even though it hasn’t

yet been scientifically demonstrated to be so, because it is correct. Then they

castigate faith as a form of unfounded belief without the least sense of irony.

More to the point, when they speak of

evolution as if it were reducible to their vary-adapt-retain

triad, they fail to have noticed that human beings—with language in

particular—have evolved to be “biologically determined not to be biologically determined”;[8] in other words, we are by our very nature “constructed” by culture, which cannot, as the dualists

would have it, be separated from nature any more than time can be separated

from matter and space, nor can our semiosphere be deconstructed within the

adapted framework of Newtonian (mechanical) physics.

Wittgenstein’s theory of language games can be instructive on several accounts when applied to semiotic discussion. Indeed, any interaction with signs, production of signs, or attribution of meaning owes its existence to its status as a move in a language game—that is, a conceptual architecture, a grammar, that we must uncover. . . Consider the Augustinian definition of the sign: something put in the place of something else (to which it is imperative to add: in a relation of meaning or representation). Wittgenstein tells us that of the elements that make up the semiotic relation (sign, modes of representation or signifying, the sign’s referent, etc.), none exists outside a language game. In an interpretive act, nothing is “intrinsically” a sign: the grammar of the language game is what makes it possible to identify the sign, its way of being a sign and what it is a sign of.[9]

Charles

Pierce (1839-1914), the semiotician, developed a classification system for

signs—any signal that refers to something and is received by an interpreter. Human

signs, he said, signify three kinds of phenomena: facts, qualities, and conventions. I point to a can of paint

and I say, “I want that paint.” The term “paint” signifies the actual existing

thing called paint, a fact. When I

browse through the swatch booklet for various paint colors, and I find the one

I want in a paint, I point to the swatch, and say, “I want this one.” In this

case, the sign—the swatch—is not paint, but a way to specify one quality of the paint, its color. When

Harriet Tubman wrote, “Mrs. Stowe’s pen hasn’t begun to paint what slavery is,” she wasn’t referring to paint or the

quality of paint, but to a more complex social issue, using certain speech conventions, like irony and metaphor. Or

in another case, we read an oral thermometer at 101 degrees Fahrenheit, and

that sign—by convention—tells us

someone has a fever, a fact. These

categories—fact, quality, convention—are what Peirce called sign “elements.”

These elements

then appoint classifications to

signs. These classifications he called index,

icon, and symbol. Index signs refer

to natural things. Icon refers to

representative things. Symbol relies

on a socially shared understanding. An actual face is indexical. A portrait photo is iconic.

A yellow happy-face emoticon is symbolic.

And we can see that these categories, from index through icon to symbol become

ever more abstract. Peirce called this “firstness,” “secondness” and

“thirdness.”

The first is that whose being is simply in itself, not referring to anything or lying beyond anything. The second is that which is what it is owing to something to which it is second. The third is that which is what it is owing to things between which it mediates and which it brings into relation to each other.[10]

[1] Von Sydow, “Sociobiology,

Universal Darwinism, and Their Transcendence.”

[2] There is a truism in logic that

says, “You cannot prove a negative”; but this is not absolutely true. The

exceptions are “proof of impossibility” (2 plus 2 cannot equal 5) and “evidence

of absence” (There is no coffee in that cup). In this case, however, the claim

“There is no God,” falls outside of either exception, because God—at least as

understood from the perspective of Christian philosophers like Aquinas—is prior