St. Catherine of Sienna, when she felt revulsion from the wounds she was tending bitterly reproached herself. Sound hygiene was incompatible with charity, so she deliberatley drank a bowl of puss.

-Mary Douglas

Some years back, I was writing quite a lot about gendered power and something called "exterminism," a term I stole from Mark Jones, a Welsh socialist I befriended on the internet. In looking at both of these topics, my editor for Sex & War, De Clarke, came up with the term "taint." In association with gender, taint works in specific ways that reinforced the boundaries between men and women and the power gradient along that boundary - and this phenomenon could be seen throughout society and across time in other areas of endeavor as well.

Taint is that invisible pollution that attached to various things - fractal-like - at differing scales: "cooties" on the playground, white women with black men (a biggie in the white South), plants that are "weeds," imaginary "germs," or even whole peoples (Jews compared to vermin by Nazis). In each case, and especially in the grown-up cases, this state of pollution was irremediable, and the final solution (pun intended) was extermination. Exterminate the germs, the bugs, the weeds, the vermin-people. And exterminism is the willingness to accept mass extermination as a solution, which Mark used to call "the final stage of imperialism."

At around the same time, while doing research for both Sex & War and Energy War, I stumbled cross a book by Linda Kintz, entitled Between Jesus and the Market.

Kintz wrote:

By dismissing arguments that are not articulated in the terms with which we are familiar, we overlook the very places where politics come to matter most; at the deepest levels of the unconscious, in our bodies, through faith, and in relation to the emotions. Belief and politics are rational, and they are not.

...and...

The intensity of mattering, while ideologically constructed, is nevertheless always beyondSo "taint" inscribes boundaries, across which power is exercised with a kind of impunity; and beliefs - no matter how sophisticated their rationales - are rooted in emotional affinity or revulsion that is pre-rational. This psychological association between convictions of various kinds (personal, cultural, religious, political) and "taint," once it is noticed, becomes ubiquitous.

ideological challenge because it is called into existence affectively.

As I began to think and write about issues relating to food, it was impossible to ignore how many of our children are suspicious of food grown in a garden, even when objectively speaking it is superior to most of that stuff we purchase in grocery stores.

There is a huge mulberry tree, just a hundred or so feet from my house, next to the city swimming pool, and it was loaded with ripe berries this summer. Each day, as I walked our dog, I made it a point to stop at the tree and eat a pint or so, and the majority of the people who traverse the parking lot next to the tree looked at me as if I just landed from Saturn.

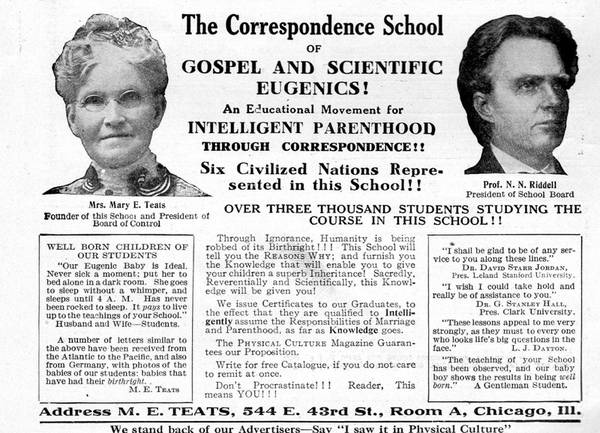

This sense of "taint" has infiltrated our consciousness to the point where we don't trust anything that is not packaged, which we assume means it is "clean." This American middle-class hyper-cleanliness and its correspondence to social boundaries (race, gender, and nationality) underwrote the eugenics movements (which is far from dead) in the early 20th Century, a topic that is thoroughly documented in Amy Laura Hall's book, Conceiving Parenthood.

One of the things that drew me into Christianity, given my recent predisposition to criticize "taint," was that Jesus committed serial infractions of the purity codes of his day - touching dead people, street people, lepers, menstruating women.... table fellowship with the "unclean."

I recently bought a copy of a little book by Richard Beck, entitled Unclean - Meditations on Purity, Hospitality, and Mortality (Cascade Books, 2011), and in the introduction he says two key things, one psychological, one theological: "[D]isgust is a boundary psychology," and (paraphrasing) - sacrifice inscribes boundaries; mercy crosses them.

For those who didn't immediately get the reference, Beck is writing about Matthew 9:13, and Jesus' confrontation with the Pharisees about "eating with sinners and tax collectors."

But go and learn what this means: 'I desire mercy, not sacrifice.' For I have not come to call the righteous, but sinners."A reference that the Pharisees would recognize, coming from Hosea 6:6.

For I desire mercy, not sacrifice, and acknowledgment of God rather than burnt offerings.The significance of this distinction is not immediately apparent, nor its relation to "disgust psychology," a field of inquiry often associated with psychology Professor Paul Rozin. Richard Beck has unpacked that significance and that relation through the synthesis of several lines of modern, mostly psychological, research.

His focus on disgust psychology is aimed at overcoming wrongs that pose as rights because they are felt as right (based, in this case, on learned feelings of disgust). His point could be made apart from theology as far as this goes, for example, in politics or personal relationships or just common sense: feeling something is wrong/right does not necessarily make it so. In this epoch of bureaucratic individualism, however, this simple declaration is not as self-apparent as it might seem.

The danger of refusing to reflect upon the psychological dynamics of faith and belief is that what we feel to be self-evidently true, for psychological reasons, might be, upon inspection, highly questionable, intellectually or morally. Too often, as we all know, the "feeling of rightness" trumps sober reflection and moral discernment. (p. 5)

Beck is writing to Christians, asking them to review their own convictions with this this tendency in mind, in particular to do so beginning with a sharp critical self-evaluation by each of us with regard to what elicits the disgust reaction.

[M]y deeper concern in this book is for the church, the people sitting in the pews. In the absence of advanced theological training or the daily immersion in critical give-and-take, the church will tend to drift toward theological positions that psychologically resonate, that "feel" intuitively speaking, true and right. (p. 6)In Linda Kintz's Between Jesus and the Market, she names the socialized emotional response that precedes our exercise of rationality or analysis as "resonance." In too many cases, this sense of resonance is conflated with the sacred. If the resonance is felt, then that feeling is indicative of contact with the sacred, which effectively forecloses any deeper examination., and which reinforces powerful emotional attachment to that which is now understood as sacred. This is true in part because we believe that transcendence is an experience associated with euphoria. Heroin addicts will tell you that their first dose of skag was akin to "seeing God."

The "feeling of rightness" can in turn undermine reflection and discernment.

Any number of postliberal theologians can be found who decry the overwhelming influence of the modern "world" on the church; and they have convinced me that their concern is valid, even central, for the church. Beck has laid out one way of understanding why and how the modern world crowds into the church and bewilders its members. I emphasize modern because, while it is not explicit in this book, the way we experience disgust today is uniquely modern, even if disgust itself - like desire - has been ever present in human experience, albeit culturally mediated.

Beck describes disgust psychology using the research of Paul Rozin, who characterizes disgust as a promiscuous emotion. While babies show no sign of disgust for anything, and will gladly put anything into their mouths, for example, by the time we are grown, we have learned to be disgusted by a whole range of things. Beck names certain foods, bodily outputs, creatures, sexual behaviors, the dead, gore, deformity, hygiene, moral offenses as a few, to demonstrate disgust's promiscuity.

The "core-disgust," the one that becomes the psychic model for other disgusts, is offense at certain oral incorporations - disgust at the fact or idea of certain things entering the mouth. Evolutionary biologists would be quick to tell us that this capacity for disgust and its association with putting things in the mouth probably had an adaptive function. Promiscuous eating can be dangerous.

Rozin developed a schema for disgust based on core-disgust (oral incorporation), in which core-disgust is externalized into "socio-moral disgust" and "animal-reminder disgust."

Let's stop there for a moment and think about disgust-reaction.

Beck begins the book with the "dixie cup" thought-experiment. Imagine someone asking you to spit into a dixie cup. Now imagine them asking you to immediately put the saliva back in your mouth and swallow it. Objectively speaking, the substance in the cup is exactly what we swallow all day long without any reaction whatsoever. Psychologically speaking, that substance was radically transformed by crossing the boundary between inside and outside the body.

The response you likely had while reading through the thought-experiment was a disgust-response, and it may have even elicited a (universal) facial expression - scrunched nose, raised upper lip.

Sometimes it is accompanied by protruding the tongue, as if to spit something out that tastes bad.

If the stimulus for this expression is immediate and at hand, as opposed to simply conversational, then it is accompanied by bodily reactions, shielding, turning away, experiencing nausea (the physical urge to expel something to the outside from the inside).

This book also reminds me a great deal of Mary Douglas' book on the anthropology of purity, called Purity and Danger, a book Beck cites, which emphasizes the associate notion of contagion. Contagion is that sense that merely coming into contact with certain people, places, and things can pollute you. That pollution is often irremediable, precisely because each time the point of pollution is recalled the disgust-reaction is recalled, viscerally, with it.

Over time, as the disgust-reaction loses its force, disgust can be replaced by a slightly more distant reaction, that of contempt. The rich might be disgusted by the poor when they are in close proximity, or inappropriately touching them, or they can be held in the less visceral contempt.

With these points in mind, let's return to Beck's and Rozin's explication.

In every case, according to Rozin and Beck, disgust can be characterized in four ways.

1 - Disgust is a boundary psychology... the point that Beck made very early.

2 - Disgust stimulates the desire for withdrawal and avoidance in mild cases, and "rejection, expulsion, and elimination" in powerful cases. Elimination can be easily translated here to extermination.

3 - Disgust is promiscuous. Disgust psychology can be broken down into core, socio-moral, and animal-reminder disgust.

4 - Disgust is accompanied by magical thinking, by ideas about contagion that are not consistent with logical or rational analysis.

One of Beck's central concerns is the latter, that "when disgust regulates moral, social, or religious experience magical thinking is unwittingly imported into the life of the church."

He then gives us four principles of contagion:

Contact: Contamination that is caused by contact or physical proximity.

Dose Insensitivity: Minimal, even micro, amounts of the pollutant confer harm.

Permanence: Once deemed contaminated nothing can be done to rehabilitate or purify the object.

Negative Dominance: When a pollutant and a pure object come into contact the pollutant is "stronger" and ruins the pure object. The pure object doesn't render the pollutant acceptable or palatable. (p. 28)

These principles are learned early. I was recently taking care of our six-year-old grandson, and he had a fit any time anyone touched his food.

"We don't have the same germs," he explained. A mere touch contaminated the food, though he happily drinks water from his bathtub and kisses the dog on the mouth. He has been taught that touching food is a means of contamination, and he has learned that this contamination is dose-insensitive. His thinking about this is magical; it does not correspond to any rational understanding of contamination-danger that transcends food-touching, for example, into bathwater or dog saliva.

"Germs" have become a contamination-marker only since the discovery of microorganisms, but contamination associated with disgust has been around since pre-history. Scripture provides examples of detailed purity codes, for example, in Leviticus, that far predate any notion of "germs." In the New Testament, those codes are still in force when Jesus is attacked by his antagonists for eating with the wrong people, not washing his hands before eating, and touching the "unclean."

One of the dramatic reversals of contamination principles in the Gospels was that a touch from Jesus rendered an "unclean" person cleansed - the opposite of "negative dominance," wherein one speck of contamination ruins the whole.

The judgement of negativity dominance places all the power on the side of the pollutant. If I touch some feces to your cheeseburger the cheeseburger gets ruined, permanently. Importantly, the cheeseburger doesn't make the feces suddenly scrumptious. When the pure and the polluted come into contact the pollutant is the more powerful force. The negative dominates over the positive.

Negativity dominance has important missional implications for the church. For example, notice how negativity dominance is at work in Matthew 9. The Pharisees never once consider the fact that the contact between Jesus and the sinners might have a purifying effect upon the sinners. Why not? The logic of contamination has the power of the negative dominating over the positive. The sinners make Jesus unclean. (p. 30)

Beck notes that the church which feels defiled by the world is reproducing negativity dominance, even though the Gospels describe an opposite process, the church redeeming the world just as Jesus cleansed lepers with a forbidden touch.

I am reminded of Amy Laura Hall's history of the progressive church in the early 20th Century United States, Conceiving Parenthood, when cleanliness was called godliness and there was a great racial line drawn between pure and impure which gave rise to a powerful eugenics movement that required a Hitler, with his special earnestness in pursuit of "racial purity," to discredit it. (Privatized eugenics is still practiced in the church, by progressives, and it still has its apologists.)

Those missions that are most Jesus-like, that bring the church into contact with the sick and despised, that act on the assumption that crossing boundaries redeems (purifies) both those who are touched and those who touch, are those that put people into bodily contact with one another (Mother Teresa or Catherine of Sienna tending the sick, for example). No practice freaks new Christians out more than foot-washing.

In addition to Rozin's research on disgust psychology, Beck employs Lakoff and Johnson's theses on the metaphorical nature of human cognition, with special attention to embodied metaphors as the bases of abstraction. Apt because oral incorporation ostensibly provides the basic form of disgust, we have all used metaphors about the "social body" or the "body politic." With the advent of modern medicine, we have more and more used the metaphor of cancer to describe putatively dangerous elements within society that might be "growing," or even among the more medically literate, "metastasizing." Beck cites 22 different metaphorical allusions to sin in the New Testament alone, purity being only one of them.

Embodied metaphors are the most intimate - death, falling, illness, sleeping, etc. Social metaphors are not quite as intimate, though still very familiar - family and citizenship, e.g.

While Beck does not use the term reification, he does describe the danger of the metaphor being treated as an unmediated fact, since all metaphors have an inherently limited utility, perhaps one reason that Paul in his letters to various churches employed a veritable smorgasbord of metaphors.

[T]hese metaphors [can] come to dominate, bias, and eventually distort the experiences of sin and salvation. (p. 36)Metaphors, Beck explains, come with entailments, associated visceral responses and forms of magical thinking.

No doubt purity metaphors communicated a deep spiritual truth, that sin in the life of Israel was a profound danger that needed to be dealt with. And yet the various entailments of purity metaphors, driven by the dynamics of disgust psychology... may create problems if they come to dominate the soteriological experience of the church. (p. 37)Because the purity metaphor so often entails a disgust reaction, it is easy for this metaphor to steer theological reflection toward exclusion and boundary-inscription, toward the kinds of othering that result in what I have called enemization - the declaration that certain persons or peoples are enemies, which is the opposite of the teachings of Jesus (though often enough compatible with the teachings of some churches).

The metaphorical translation of core disgust, explains Beck, shapes sociomoral disgust (disgust at particular kinds of moral "failure" and even against whole peoples) and animal-reminder disgust, revulsion at reminders of our animal nature (which stimulates existential dread at the inevitability of death).

The unexamined premises of this direct and extrapolated disgust response contribute to certain consequences; and many of these consequences, says Beck (and I agree wholeheartedly), are damaging to the church, which we ought to see as the body of Christ - that same Christ who was born in a shitty stable with farm animals looking on, who ate with sinners, put his hands on skin lesions, rubbed spit in people's eyes, allowed street women to kiss his feet and wash them with their hair, who washed the feet of his own disciple, and who re-imported a living, sweating, dying human body back into the Sabbath.

Those consequences listed by Beck are summarized thus:

1. Disgust is an expulsive emotion. Thus, "moral purity" is attained (and maintained) by acts of separation and cleansing, and quarantine.

2. Purity metaphors activate the "magical thinking" of contamination logic. Thus, moral reasoning about "purity violations" is often irrational. For example, contact and proximity become important considerations. Dose insensitivity frames the violation in catastrophic terms. And purity violations are felt to be permanent and beyond rehabilitation.

3. The Macbeth Effect [a phenomenon tested in psych labs]. Given the strong psychological association between physical cleansing and spiritual purity, laboratory studies have shown how acts of physical cleansing - ritual or real - can replace and substitute moral effort and repentance. Hand washing literally substitutes for acts of compassion and justice.

4. Although all sins are generally considered to be purity violations (given understandings of God's holiness in both the Old and New Testaments) some sin categories are uniquely structured by purity metaphors. Specifically, sexual sins are often regulated by the metaphor of "sexual purity." This uneven use of purity metaphors across the domain of sin behaviors may be one explanation for why certain sin categories are felt to be more toxic than and severe within some faith communities. Purity sins tend to be unfairly sand unreasonably stigmatized in these groups. This creates greater shame and self-loathing for certain classes of sin.

5. Finally, the disgust reaction in the face of purity violations leaves us communally dumfounded. Debates about purity violations are often immune to rational conversation or discussion. This is due to the fact that people sit with different felt experiences regarding what is or is not improper, degrading, or illicit. A "feeling of wrongness" is the only warrant deployed and we are stuck if people don't share those feelings. This dumbfounding often occurs when conservatives and liberals discuss moral views. (pp.144-145)

I have a quibble here, but it is just that - a quibble.

It is blatantly true that many people find it difficult to be non-defensively self-critical... with themselves. That is the obstacle (the skandal?) to faithfulness of any kind. I speak as a sinner and a witness-still-a-sinner. The implicit call to do exactly that, by an honest and unsentimental inventory of our own disgust-responses and the beliefs that they entail, is a major reason why this book was so helpful to me. It has given us a language to talk about it.

I am unconvinced, however, by the argument stemming from the research of Jonathan Haidt and Jesse Graham, cited by Beck, on liberals and conservatives, and this is - in my opinion - the weakest argument in the book (albeit one that the rest of the argument can do without).

Haidt and Graham are psychological researchers who tested conservatism and liberalism along five so-called "moral foundation" axes: harm-care, fairness-reciprocity, in-group-loyalty, authority-respect, purity-sanctity. Obviously, Beck uses these with a special emphasis on the last, purity-sanctity; and not surprisingly, conservatives place greater emphasis on authority and purity than on harm-care and fairness, but the implication that these categories occur prior to conservatism and liberalism, as explicated philosophical positions, and not as their logical outcome, is less than convincing.

Because respondents could not clearly describe the bases of their convictions - which the researchers and Beck himself call "moral dumbfounding" - is taken to mean that there is a Humean dynamic of emotional prejudice that is prior to reason at work. And while I myself validated this idea in my earlier references to both this book and my citation of Kintz's work, in this case, I think too much was taken for granted in the comparison between liberal and conservative.

Few people are capable of describing their own beliefs at a philosophical level, even when their intuition of them may be perfectly coherent within a given system of thought. Dumbfounding, in this example, may not be the result of Humean desire-priority (which is a bit different, actually, from emotional resonance as we have described it here), but of simple inarticulateness.

MacIntyre

As Alasdair MacIntyre pointed out in After Virtue, the liberal and conservative tendencies within Liberalism (which is the dominant philosophical current for both) can be traced to two different and well-articulated positions (a la Rawls and Nozick) that have incommensurable premises (neither of which says anything about purity). Both positions (liberal and conservative) within Liberalism share the same defect in that they pretend to be universalizable (an imperial pretension of the Euro-American Enlightenment) and they are based on a non-existent abstract "individual" that is embodied by no particular actual person. Haidt and Graham's categories are perilously close to that same defect of universal pretense and hyper-abstraction; and they are suspiciously close to what appears to be a liberal-Liberal debate agenda.

The five categories above are not universalizable precisely because their meanings and contexts are so dramatically different from culture to culture, age to age. Here there is an assumption of the Western metropole in the age of bureaucratic individualism as normative, which I find problematic as a Christian with some very non-modern convictions about what is and is not true, what is and is not right.

Beck's point in the chapter "Divinity and Dumbfounding," that many people hold beliefs that are largely unexamined, is well-taken, but this particular citation (Haidt and Graham) was not particularly helpful. I understand that he wants to encourage people to examine their own beliefs in the light of the psychology of disgust - a goal I share, and the reason I am otherwise wholeheartedly endorsing this book. I also share his suspicion that purity concerns reinforce certain tendencies in church, even those that are sometimes characterized as liberal-conservative, but I tend to believe that Liberalism (the philosophical tradition of modernity) has more explanatory power than this "study" for understanding how the church - as the body of Christ - has gone astray within modernity. Gendered power, too, which is concealed yet operative within modernity. The real value of disgust psychology, in my opinion, and the great value of this book, is in seeing all the ways disgust can be mobilized, and beginning then to discern the meaning of Matthew 9.

As any combat veteran knows, however, disgust at an enemy people may not exist prior to entering a conflict, but appear only after the fact when the soldier's position vis-a-vis suspicious or occupied people compels him to dehumanize (Beck called this "infrahumanization") them to overcome cognitive dissonance. The Stanford Prison Experiment comes immediately to mind. The same may apply to philosophical commitments that exist prior to the experience (learned as a situational or philosophical accommodation) of disgust.

Moreover, as Amy Laura Hall's book, Conceiving Parenthood, shows, the liberal-Liberal tradition has a history of disgust-based and imperial psychology underwriting many of its assumptions every bit as much as conservative-Liberals. Present-day discussion of sexuality, in particular, have papered over this history and can leave the impression that "progressives" - a term I dislike quite a bit - are those who have most effectively overcome this moral dumbfounding.

Quibble over.

With that said, Beck's point in the same chapter is still valid when applied to many of our Western contemporaries. "Moral dumbfounding," a term deployed by Haidt, can be more than mere inarticulateness. Moral dumbfounding is the inability to articulate a "moral warrant," that is, a reason why you think something is right or wrong, beyond that it is "just right" or "just wrong." Here is where Beck, Haidt and Graham, and Kintz all come together.

[T]he moral dumbfounding research clearly shows how normative judgements are often affective judgements that motivate, in a post hoc fashion, a search for a rational warrant. The warrant in this case is not the decisive factor in reaching normative judgement. Rather, we seek rational warrants to justify our feelings to others, to give "excuses" as it were, for why we feel the way we do in a particular situation. (p. 63)Beck tells the story of a pastor who preached a sermon wherein he used the word "crap," inciting several members to anger because they felt his use of a word associated with excrement was somehow defiling (sanctity of) the church sanctuary. The boundaries that are built up between sacred and profane, he points out, become boundaries that re-inscribe notions of Us versus Them, a re-inscription that ought to trouble Christians, given how Jesus trampled on these boundaries repeatedly and provocatively.

The analog of core-disgust, or its extension, is socio-moral disgust.

In the social arena, Beck describe perhaps his most important thesis - that love and disgust are reciprocal. He prefaces this conclusion with a reflection on "self," boundaries, and incorporation.

As the self gets symbolically extended so does disgust psychology, the primal psychology that monitors the boundary of the body. Disgust accompanies the self as it reaches into the world, continuing to provide emotional markers denoting "inside" and "outside," the boundary points of the symbolic self. (p. 86)

Anyone who watched the films Meet the Parents and Meet the Fockers will remember Robert DeNiro's character, Jack Byrnes', hilariously described "circle of trust."

"With this understanding of self in hand, we are well positioned to understand human love, intimacy, and relationality. Specifically, as the notion of "one flesh" highlights, love is a form of inclusion. The boundary of the self is extended to include the other. The very word intimacy conjures the sense of a small, shared space. We also describe relationships in terms of proximity and distance. Those we love are "close" to us. When love cools, we grow "distant." We tell "inside" jokes that speak of shared experiences. We have a "circle of friends." "Outsiders' are told to "stop butting in." We ask people to "give us space" when we want to "pull back" from a relationship. In sum, love is inherently experienced as a boundary issue. Love is on the inside of the symbolic self.While I consider this thesis very important in Unclean, I have another quibble.

Given that disgust monitors the boundaries of selfhood and intimacy it should come as no surprise then that love involves a suspension of disgust and contamination sensitivity. More strongly, disgust is a prerequisite of love. Love, to be love, requires a backdrop of disgust. For someone to move "inside" there must be a preexisting condition of having been "outside," being exterior and other. In short, disgust establishes boundaries of contact. Love enters as a secondary mechanism when those boundaries are transgressed or dismantled. (pp. 86-87)

There are four forms of love by C. S. Lewis' reckoning, and I'll use them as the basis of my discomfort with some examples given in the book: storge, phileo, agape, and eros.

Storge (pronounced 'store-gay') means affection, fondness through familiarity. Philia (pronounced 'fil-ya') is freindship. Agape (pronounced uh-gah-pay) means unconditional love - in Christian terms caritas, the love for others that reflects God's love. Eros refers to love with the element of sex, which Lewis differentiates from simply wanting sexually, which he called Venus.

The problem at hand is that Beck concentrates his examples on erotic love as exemplary of love without some critical distinctions, especially as it relates to the overcoming of disgust.

Short story. When I was a lad of 14, I was taken by some friends to a special bar on the outskirts of St. Charles, Missouri, called Mr. B's Lounge, where having one's permanent teeth qualified you to be served alcohol. I was a skinny kid, freckled, with cowlicks all over my head, shorter than anyone in my class, male or female, with jug ears and a gap in my front teeth that invited comparisons to Alfred E. Neuman. I had little experience of sex or girls in general and was painfully shy around them.

On about my third watery draft beer, I found much of my social anxiety disappearing, when suddenly a girl I only recognized from school came over to me with unfocused eyes and asked me if I'd like a kiss. Full of liquid confidence, I assented, whereupon she locked her lips onto mine and began pushing her tongue into my mouth. I don't know if I'd thought much about that before, or if I would have experienced a disgust reaction to the idea, but after a momentary shock I realized that what she was doing felt better than anything in my memory and it gave me goosebumps on my legs. She then returned to her own crowd, leaving me to continue my foray into bar-flying (which would eventually lead me to wishing myself dead as I puked my guts out on the floor in the back of my buddy's dad's 1956 Chevrolet).

I did not know that girl, nor did I love her, though I found myself wanting to repeat this experience as early and often as possible.

Beck uses the "tongue in the mouth" example as one of love overcoming disgust. While I would support Beck's thesis that love entails overcoming boundaries, and that one of those boundaries is that inscribed by disgust (ref: Catherine of Sienna in the opening passage), and while I would support this thesis with regard to agape, storge, and philia, in the realm of eros it is highly problematic. The reason is that eros - love with the component of sex - must be understood, even in relationships that we don't often critique as pathological, in the light of power. Sex and power are linked, and that link reveals something about boundaries that was not covered in Unclean.

It was however covered, along with the topic of transgression (re: Beck, above), in a book by Nancy C.M. Hartsock.

That aspect of disgust as a boundary psychology that is not described in Unclean is that wherein sex understood as "nasty" becomes paradoxically attractive. Nancy C. M. Hartsock does address this, though not in the language of disgust psychology, but feminism, as the eroticized thrill of transgression that comes from crossing boundaries. In her book, Money, Sex, and Power - Toward a Feminist Historical Materialism (Longman, 1983), she writes:

The dichotomy between spiritual love and "carnal knowledge" is recreated in the persistent fantasy of transforming the virgin into a whore. She begins pure, innocent, fresh, even in a sense disembodied, and is degraded and defiled in sometimes imaginative and bizarre ways.

Transgression is important here: Forbidden practices are being engaged in. The violation of the boundaries of society breaks is taboos. Yet in the act of violating a taboo, of seeing or doing something forbidden, does not do away with its forbidden status. Indeed, in the ways women's bodies are degraded and defiled in the transformation of virgin into whore, the boundaries between the forbidden and the permitted are simultaneously upheld and broken. Put another way, the obsessive transformation of virgin into whore simply crosses over and over again the boundary between them. Without the boundary, there could be no transformation. And without the boundary, the thrill of transgression would disappear. (p. 172)

She also summarizes the lure of pornography as the substitution of control for intimacy, which is attractive because it evades the danger (to men in particular) of fusion, that same experience of losing oneself in union with another that Beck describes as love: the breakdown of the boundary around the self. In much pornography, the misogyny is pronounced, and women are described - erotically - as objects of disgust, who are humiliated by sexual contact. Ejaculation onto the body or the face of women, for example, is a common porn convention in which the substance that becomes unclean upon exit from the body is used to contaminate or defile the female.

This disgust, this hatred, is eroticized largely at the expense of women by virtue of women's collective subordination to men. There may be no Jew, no Gentile, no slave, no free, no woman, no man in the Body of Christ; but in our society, that woman-man boundary cannot be effaced or leapt over by a decree. It requires Christian men to become aware of that power, of how it works as social privilege, and of how it is implicated in our most intimate relations, if we are to unlearn what needs unlearning, and if we are to understand how to renounce that power.

As Hartsock points out, this eroticized disgust/transgression boundary can be crossed again and again. As we know from accounts of pornography addiction, the border-crossings can become routinized, leading to an escalation dynamic, where the demand for more and more degrading, edgy, and "extreme" acts of degradation are required to achieve the same instrumental thrill.

Disgust actually enhances the thrill, which must lead us to question how boundaries function in relation to privilege. Just as the imperial trooper can cross a boundary into the forbidden zone to be temporarily released from the taboo on killing, and just as he can return - if he survives - back to his position of relative comfort and safety (privilege), men in a patriarchal society can cross boundaries with thrill-seeking in mind (duplicating that dopamine rush I experienced at Mr. B's Lounge in 1965), and what they feel and do has nothing to do with love and everything to do with control and objectification.

Beck writes...

[T]he biological, animal function of sex isn't all there is to human sexuality. For humans, sex can be experienced as a deeply spiritual activity. Sex is often an experience of spiritual exultation and transcendence. Further, the deepest feelings of human love and union are often experienced within the sex act.What is unstated here, and unrecognized altogether, is that sex is experienced differently between men and women because there is a power differential between men and women that is invariably implicated in all sex. And power is something Jesus subverted, too.

In short, sex is dual. (p. 159)

Sexuality cannot stand as a floating signifier. Hartsock:

One of the first questions to be addressed is what is meant by sexuality. Definitions of what is to be included often cover many aspects of life. For example, Freud included but did not clarify the interrelationships among such various things as libido, or the basic tendency toward being alive and reproducing, the biological attributes of being male or female, sensuality, masculinity and femininity, reproductive behavior, and intense sensations in various parts of the body, especially the genitals. And Jeffrey Weeks, summarizing our culture's understanding of sex, argues that in our society "sex has become the supreme secret," which is at the same time the "truth" of our being. It defines us socially and morally. Moreover, the common understanding of sexuality treats it as a "supremely private experience," which is at the same time "a thing in itself."Beck's own reference to animal-reminder disgust, particularly mortality-reminder disgust, is pertinent here, because women have served as signifiers for men's anxieties about body and mortality, and women have been men's targets of projection.

My own reading of the literature suggests that in contrast to these definitions, we should understand sexuality not as an essence or set of properties defining an individual, nor as a set of drives and needs (especially genital) of an individual. Rather, we should understand sexuality as culturally and historically defined and constructed. Anything can become eroticized, and thus there can be no "abstract and universal category of 'the erotic' or 'the sexual' applicable without change to all societies." Rather, sexuality must be understood as a series of cultural and social practices and meanings that both structure and are in turn shaped by social relations more generally [italics added]. (p. 156)

It was St. John Chrysostam, writing in the 3rd Century, who said:

It does not profit a man to marry. For what is a woman but an enemy of friendship, an inescapable punishment, a necessary evil, a natural temptation, a domestic danger, delectable mischief, a fault in nature, painted with beautiful colors?We Christians have a lot of repenting to do. I, as a man, have a lot of repenting to do. But to "turn around," as repent means, we have to know where we've been and where we are going. Without these insights into the constructed and power-inflected character of any "sexuality," we will continue to treat sex as if it is experienced the same by men and women, as if sex is merely dual - animal and spiritual. Eros doesn't solely exist along this one axis. To treat of it thus is to make the experience of men the norm.

The whole of her body is nothing less than phlegm, blood, bile, rheum and the fluid of digested food ... If you consider what is stored up behind those lovely eyes, the angle of the nose, the mouth and the cheeks you will agree that the well-proportioned body is only a whitened sepulchre.

Batallie

For a terrifying look at how men experience eros in male dominant society, where men define themselves against women, check any popular porn site and see what women are called, how they are treated, then reflect on why women check the back seats of cars before they get in and men don't. Failing that, here is an excerpt from the academically respectable French philosopher-pornographer Georges Bataille, quoted by Hartsock on page 158, where he explains (assuming male experience to be normative) that sex and killing are similar in that each...

...is intentional like the act of a man who lays bare, desires and wants to penetrate his victim. The lover strips the beloved of her identity no less than the bloodstained priest his human or animal victim. The woman in the hands of the assailant is despoiled of her being... loses the firm barrier that once separated her from others... is brusquely laid open to the violence of he sexual urges set loose in the organs of reproduction; she is laid open to the impersonal violence that overwhelms her from without.Lover equals assailant. Woman equals victim. How are women navigating this reality; and can any woman experience sex in the same way as most men?

There is now a popular truism that "rape is not about sex, but about power." This is patently untrue, and it is repeated to protect "sex" as a floating signifier stripped of any context. Real sex is "good" (a liberal shibboleth), while rape is about power. But rape exists on a continuum of sex inflected by power - as all actual sex is - again as a "transgressive" line in the sand defined by "consent" that only begins during the act, with no regard for power relations that are in the background prior to the act. Ask any woman if she has ever "consented" to sex she didn't want based on her vulnerability to or dependence upon a man, or to keep peace in the household.

I wrote in an earlier post that men, males, according to Hartsock, are heavily socialized to resist fusion, and that fusion with the female "other" is understood as a threat when masculinity is defined primarily as not-woman, that is, against women.

This particularly important because of what Beck does write about "the influence of disgust upon moral reasoning and the experience of sin within the life of he church."

Although we recognize extreme cases of sociomoral disgust in incidents of genocide and hate, we often fail to recognize that sociomoral disgust is affecting all of us and is an everyday affair. Examples of how soical disgust affects daily social interactions: finding people "creepy" or "nauseating"; the experience of the moral circle (the flow of human kindness); the psychology of infrahumanization ("humanity ends at the border of the tribe"); and he emotion contempt (often seen in social hierarchies).Yet disgust alone does not erect and monitor boundaries, and the play of privilege (in hierarchies) in crossing boundaries (for a transgressive buzz) must be part of our discernment of disgust. Masculine fear of fusion erects another kind of boundary in which disgust is conflated with desire and confused with love (from a normative male perspective).

Critically, it was observed that disgust and love are reciprocal processes. Disgust erects and monitors boundaries of the self, and love, as a secondary process, allows those boundaries to be dismantled or blurred. This is most clearly seen in physical intimacy, where access to the body is granted. (pp. 145-146)

I agree that the "will to embrace" (which might be a subset of a "will to accept") is an important corrective to moral dumbfounding based on learned disgust-reactions; but given the centrality of male dominance as an ancient (albeit evolving) hierarchy that serves as the model for all hierarchies, and given that the male "will to embrace" more often than not is unaccompanied by any deep discernment of how that hierarchy - or male privilege - operates, factoring disgust-based moral dumbfounding into our thinking about church without that discernment might very well leave untouched male identity constructed around the fear of fusion and the inability to distinguish between one "will to embrace" and another.

End of quibble 2.

Maria Mies has written about male disgust with women being related to an aversion to reminder of mortality. Women are traditionally, and often inevitably, warmly and wetly embodied in menstruating, in bearing children, in nursing, in caring for children (feeding and cleaning). But here I must be reminded that our middle-class Western aversions to the body are relatively new. Catholic teaching for centuries emphasized, "Be ever mindful of death," even placing a skull at the bottom of the crucifix (Adam's) as a reminder.

Squeamishness about sex, apart from a few of the male saints, was not universal until the Victorian era. Ancient Jews even had a blessing to say when their bowels moved. Carolyn Merchant noted that we did not begin separating the dead from the living until after the Enlightenment. For these reasons, the research cited in Unclean, most done by psychologists relying on carefully circumscribed methods, ought not be generalized. Beck gives a beautifully clear account, however, of present-day, American, middle-class, white society - where this research really does apply.

Referring to Arthur C. McGill's book, Death and Life: An American Theology, he says...

"Refusing to be lacerated by the horrors of life, [Americans] create [a] world of life-affirming buoyancy." Americans accomplish this illusion by devoting themselves "to expunging from their lives every appearance, every intimation of death... All traces of weakness, debility, ugliness, and helplessness must be kept away from every part of a person's life. The task must be done every single day if such persons are to convince us that they do not carry the smell of death within them." As we have seen, disgust aids in this death repression. Feeling revulsion and contempt in the face of physical failure and decay, in both ourselves and others, we push death and need out of consciousness. (p. 176)

The modern church is situated in liberal society, like it or not, and the kinds of research Beck cites is relevant to modern church members. In talking about how church folk want to cordon the sacred (the sanctuary) from the profane, understood as the body, this book is on point. The cosmic disembodiment of Christ is the antithesis of the Incarnation and all it means.

Psychologically, we feel that purity and holiness is achieved by removing ourselves from the gutter and waste. This impulse also makes us want to protect God from the disgusting aspects of our bodies and existence. God needs to be quarantined. [italics in the original] (p. 152)Indeed, Stanley Hauerwas once said, and I am paraphrasing, that if you need to protect it, it's not God.

In the light of the Incarnation, the divine moving into the grit oflife, this holiness via a flight from the body seems to be pulling us in the wrong direction. The church is pulled away from life rather than toward a deeper participation. [italics in the original] (p. 153)Beck calls this Incarnational ambivalence.

Christians throughout the centuries have struggled with the scandal of the Incarnation, Jesus' full participation in the human condition. There is something illicit and vulgar about imagining Jesus participating in the metabolic life of the body. (p. 182)Here is Ivan Illich on Incarnation...

God didn't become man, he became flesh. I believe... in a God who is enfleshed, and who has given the Samaritan, as a being drowned in carnality, the possibility of creating a relationship by which an unknown, chance encounter becomes for him the reason for his existence, as he becomes the reason for the other's survival - not just in a physical sense, but a deeper sense, as a human being. This is not a spiritual relationship. This is not a fantasy. This is not merely the ritual act which generates a myth. This is an act which prolongs the Incarnation. Just as God became flesh and in the flesh relates to each one of us, so you are capable of relating in the flesh, as one who says ego, and when he says ego, points to an experience which is entirely sensual, incarnate, and this-wordly, to that other man who has been beaten up. Take away the fleshy, bodily, carnal, dense, humoural experience of self, and therefore of the Thou, from the story of the Samartian and you have a nice, liberal fantasy, which is something horrible.

And Walter Brueggemann:

Touching the unclean out of compassion, literally or figuratively, is a rebuke to those who exclude, ignore, avoid, and revile others. Across those boundaries are power gradients, and so the subversion of boundaries is a politically-loaded practice, a form of subversion.Compassion constitutes a radical form of criticism, for it announces that the hurt is to be taken seriously, that the hurt is not to be accepted as normal and natural but is an abnormal and unacceptable condition for humanness.

I was deeply impressed this year when the newly appointed Pope Francis washed the feet of a Muslim woman prisoner. I am quite sure that others were scandalized. Foot washing is a practice that evokes a great deal of anxiety for new Christians, precisely because of the fear others will find one's feet disgusting. This past year, when I was on the teaching team for RCIA, we had to calm people down a bit before the Holy Thursday's foot washing.

People whose vocations require them to ignore disgust boundaries - plumbers, nurses, moms, etc. - generally show that actually-existing disgust, disgust with an object before it, is learned, and that it can be unlearned. This is promising not in reference to social policy - a preoccupation I share less and less in each day - but with regard to how young people are formed. Those of us, who for whatever reasons, have unlearned disgust that had hurtful entailments, can intentionally model acceptance for younger people in ways that prevent them having to learn these associations in the first place. We have real agency here, far more than we have in the arena of social policy, especially as church. This is where the postliberal vision of church as both narrative community and practical politics is particularly apt.

What would be the significance of an alcoholic's LACK of boundaries here? Is there no transgression then?

ReplyDelete