I know this is being lauded by gay rights activists, and I am more than familiar with the rationale, given that I have closely followed the same struggle for full inclusion into the armed forces during and after a career in the Army. That's not what's on my mind today, however . . . the rationale for fighting for full entry into either the BSA or the United States Armed Forces. I'm more interested in what was "won" for those excluded and how that gets set aside from the advocacy for or opposition to full inclusion in both.

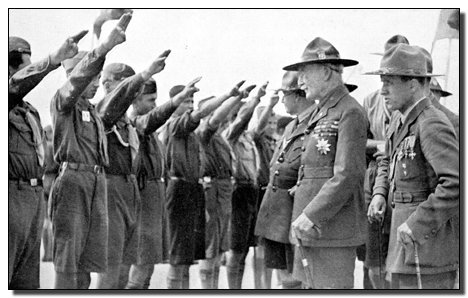

They have more than a few common origins.The American Boy Scouts were founded in 1910, modeled on an English version of the same founded by General Robert Baden-Powell, as an antidote to urbanization’s deleterious effect on boys’ "manliness," individualism, and patriotism. Many of the early scout leaders were former military men, and the male mythos they promoted was what has been called frontier masculinity, with figures like Daniel Boone as archetypes.The closing of the frontier was considered by Progressive men and muscular Christians alike to have created a crisis of masculinity.

Progressive here refers to the late nineteenth-early twentieth century movement associated with, among other things, empire-building, public hygiene and eugenics. After the Civil War, the United States had maintained a very small standing military, and these cobbled together outfits under the command of influential men with military fantasies were necessary to fill the gap when the opportunity to pounce on Spanish colonies presented itself. In 1898, a young Lieutenant-Colonel named Theodore Roosevelt – from a fabulously wealthy family that had made its fortune as land speculators in Manhattan – was leading a cavalry regiment in Cuba during the Spanish-American War. Roosevelt became the Progressive's principle political spokesperson.

Meanwhile, a dramatic change had occurred in the status of women. As taxed wage labor became the predominant means for making a living for men without land, women – who in farm families were part of the essential production process – were transformed into something called housewives. We are not talking here about the businessman’s wife in her piano parlor, but about the far larger numbers of women who were married to wage workers.

The vernacular economy of the subsistence farm was being swept away by an industrial economy; and women in the home became “shadow workers,” unwaged participants in the process of adding value to commodities in households that no longer produced, but only consumed.

Ivan Illich explains:

I designate as shadow work the time, toil, and effort that must be expended in order to add to any purchased commodity the value without which it is unfit for use. Therefore, shadow work names an activity in which people must engage to whatever degree they attempt to satisfy their needs by means of commodities . . . When a modern housewife goes to the market, picks up eggs, then drives home in her car, takes the elevator to the seventh floor, turns on the stove, takes butter from the refrigerator, and fries the eggs, she adds value to the commodity with each one of these steps. This is not what her grandmother did. [Illich is writing in 1982.] The latter looked for eggs in the chicken coop, cut a piece from the lard she had rendered, lit some wood her kids had gathered on the commons, and added the salt she had bought . . . The grandmother carries out woman’s gender-specific tasks in creating subsistence; the new housewife must put up with the household burden of shadow work.

In the late nineteenth and early twentieth century had not seen the appliances that this latter twentieth century housewife used, this drudging working class reflection of the coffeehouse and parlor – the shop floor and the consuming household – characterized the new urban family model: an economic point of consumption, where the man brought home some money and the woman used it to get those things to which she then added enough value to make them fit for use. Man was being redefined as earner, woman as consumer, domestic servant, child care manager, and sex object/breeder.

Even today, if we watch daytime television – which is still oriented toward “housewives,” even with many more women earning wages – we will see advertisements for value-addable family “needs,” products to assist with domestic chores, and products that claim to increase a woman’s sex appeal.

Maria Mies made note that before a new or refreshed process of domination can occur, the object of that domination must be exteriorized, or separated. She also noted that when this separation is characterized as progress, it usually means progress for one subject with reciprocal “retrogression” for the other. In the process of “housewifization” – her neologism – men become even more public beings and women even more private. For those in vernacular (subsistence) economies, where production and consumption were co-located, the work was gender divided, but the complimentary tasks were not alienated in the sense of wage labor or household drudgery.

Mies showed a correspondence between the practical and ideological exteriorization of women and the exteriorization of nature and colonies in the period under review. Men are conquerors. What men conquer are women, nature, and colonies. It was during this period that racialized social Darwinism was gaining ground, and many anthropological speculations (origin myths) revolved around the fable of some ancient “man, the hunter.” War was a central feature of this trinitarian conquest-episteme.

The historical development of the division of labor in general, and the sexual division of labor in particular, was/is not an evolutionary and peaceful process, based on the ever-progressing development of productive forces (mainly technology) and specialization, but a violent one by which first certain categories of men, later certain peoples, were able mainly by virtue of arms and warfare to establish an exploitative relationship between themselves and women, and other peoples and classes.

Within such a predatory mode of production, which is intrinsically patriarchal, warfare and conquest become the most ‘productive’ modes of production. The quick accumulation of material wealth – not based on regular subsistence work in one’s own community, but on looting and robbery – facilitates the faster development of technology in those societies which are based on conquest and warfare. This technological development, however, again is not oriented principally towards the satisfaction of subsistence needs of the community as a whole, but towards further warfare, conquest and accumulation.

Western civilization after the Enlightenment developed through the conquest of colonies. American expansion after the Civil War was driven by a war against indigenous people until the Spanish-American War, wherein the United States began expanding its extra-continental colonies through inter-imperial war.

The normative/ideal Western male was defined by his separateness, by boundaries separating him from women, from nature, and from the “unwashed masses” of conquered colonies. He was unlike any of these, and yet he was obliged to transgress those boundaries in order to subdue women, nature, and colonies. Colonies were disciplined for extraction. Nature was tamed. Women were domesticated.

By the time of the Victorian period, or the latter part of the nineteenth century, anxious and influential men like the founders of “muscular Christianity” began to describe a “crisis of masculinity” among European and North American white men based on a surfeit of gentility and migration to the “soft life” of the cities. One of the most vocal of these critics would become the President of the United States: Theodore Roosevelt.

Roosevelt was in many respects an emblematic leader in the late nineteenth century and early twentieth century, when “a fear about the softness of American society raised doubts about the capacity of the United States to carry out its imperial destiny.”

Continental expansion had ceased, and with it the national myth of frontier masculinity. There was a fear in some circles that a loss of masculinity constructed as conquest among citizens would lead to national "impotence." Churches spread this fear as well, which accompanied the fear that urban life would bring out “a moral softening.” Immigration had increased, and part of this discourse included talk about “race suicide.”

Imperialism was embraced as Manifest Destiny, as the Christianization and civilization of the dark others. Roosevelt wrote of American opposition to the bloody occupation of the Philippines:

I have scant patience with those who fear to undertake the task of governing the Philippines . . . who shrink from it because of the expense and trouble; but I have even scanter patience with those who make a pretense of humanitarianism to hide and cover their timidity, and who cant about “liberty” and “the consent of the governed” in order to excuse themselves from their unwillingness to play the part of men. Their doctrine, if carried out, would make it incumbent upon us to leave the Apaches of Arizona to work out their own salvation, and to decline to interfere with a single Indian reservation. Their doctrines condemn your forefathers and mine for ever having settled in these United States.

Racial superiority discourse was not new, but by the turn of the century it had taken on a distinctly Darwinian idiom – not to be confused with evolutionary biology, which makes no reference to “survival of the fittest.”

Just as American Protestantism had impelled its people to financial success as a sign of God’s providence, men felt compelled to live into the idea of fit-ness. Muscular Christianity was literally about muscles inasmuch as it promoted something then called “physical culture,” the progenitor of bodybuilding and today’s apparently contagious Adonis complex among males.

Lampooned by social critics like Sinclair Lewis and H. L. Mencken, muscular Christianity did achieve a foothold in American culture among the influential, and contributed significantly to turn of the century militarism. In fact, it has enjoyed a resurgence as this book is composed through the likes of Mark Driscoll and other celebrity preachers of Christian machismo.

Then, as now, it was a reaction to the mass insecurity experienced by men in a period of gender instability. Fashion and other commodity promotion phenomena had introduced the manufactured preoccupations of women into the public sphere, i.e., the marketplace, where women’s consequent public visibility was perceived as a threat, especially to impressionable urban boys. In the novel, Tom Brown at Oxford (1861), its author, and one of the founding fathers of “muscular Christianity,” Thomas Hughes, wrote, that it is “a good thing to have strong and well exercised bodies . . . The least of the muscular Christians has hold of the old chivalrous and Christian belief, that a man’s body is given him to be trained and brought into subjection, and then used for the protection of the weak, the advancement of all righteous causes, and the subduing of the earth which God has given to the children of men.”

Theodore Roosevelt said that this book should be mandatory reading for Americans.

In 1910, W. W. Hastings, the Dean of a physical education school in Battle Creek, Michigan, delivered a lecture entitled, “Racial Hygiene and Vigor,” which combined the themes of hygiene, eugenics, racial superiority, and “physical culture,” and which closely mirrored the thought of Roosevelt.

Roosevelt was raised by a stern father who never forgave himself for mustering out of the Civil War, and who indoctrinated the frail, asthmatic boy with frontier “conquer nature and the savages” masculinity. By the time Theodore was grown, however, the frontier had been “tamed,” and young Theodore had to direct is conquest-imperative elsewhere. He became an avid hunter, testing himself against nature as it were, and he joined the cavalry to participate in the Spanish American war. The new frontier was colonies, where the American nation could emulate their British predecessors by building an exploitable periphery.

As to women? Theodore had inherited the nineteenth century, Victorian domestic femininity tradition, but his main concern with women was as breeders for “fit” children to populate the nation. In his 1905 speech on “American Motherhood,” he said:

No piled-up wealth, no splendor of material growth, no brilliance of artistic development, will permanently avail any people unless its home life is healthy, courage, common sense, and decency, unless he works hard and is willing at need to fight hard; and unless the average woman is a good wife, a good mother, able and willing to perform the first and greatest duty of womanhood, able and willing to bear, and to bring up as they should be brought up, healthy children, sound in body, mind, and character, and numerous enough so that the race shall increase and not decrease .

In the March 2005 edition of The Organization of American Historians Magazine, Bruce Fehn published an article, “Theodore Roosevelt and American Masculinity,” in which he wrote, “With the help of cooperative news writers, who continually published stories of his physical exploits, Roosevelt became the ‘most famous purveyor’ of manly activity as an antidote to ‘the fear of the feminization of American men.’”

Two aspects of this highly publicized and emblematic masculinity were notable: the triune conquest-trope with women, nature, and colonies as its objects, and defining masculinity against women – that is, being manly means precisely being not like a woman. There is a dual political backdrop here that includes the emergence of feminism, such as it was, white feminism that demanded both the franchise and reproductive control, and the drive for extra-national colonization to feed economic expansion.

The expectations of men (beginning as boys) in social situations was that they would learn the arts of domination – physical, romantic, political, and symbolic. This conditioned desire on the part of men to adopt the role and hold the status of dominator requires objects of domination for its fulfillment. What is central to Western modernity – as an economic accumulation regime – is the incorporation of colonial expansion into the material economy as well as the symbolic one.

Mies writes not about the development of Medieval Christianity nor about Ancient Sumerians, but about the emergence and evolution of Western modernity. The domination of women preceded the other two forms of domination – nature and colonies. The peculiar form of domination of nature, however, is explicitly associated with the Enlightenment and what Carolyn Merchant called “the death of nature.”

Colonies corresponded to the domination of (unruly, chaotic, like-a-woman) nature as an integral practice of empire, with its core-periphery dynamic. The emerging order required the state to ensure profit, which meant access to feedstocks, a supply of workers, the legal right to dispose of waste at low or no cost (called externalization), and a market of consumers big enough to soak up the product. Because it was inherently expansionist (called “growth” by economists), this required businessmen to reach beyond their borders for some or all of these as they became exhausted or unavailable in the cores. This required the intervention of the state to claim distant lands and subdue restive or resistant peoples. This also required a moral justification, because there was enough residual commitment, in a Christian society, to caritas to find the idea of bald-faced plunder offensive and irreconcilable with the faith. That justification became progress, which was closely associated with imperial conquest, bourgeois respectability, and "civilization."

In 1899, Rudyard Kipling published a poem in McLure’s, a popular magazine of the time, entitled “The White Man’s Burden.” The poem was written explicitly as an apology for colonialism, and it claimed the “white man’s burden” was to civilize the darker races. Plunder was transformed into altruism, albeit an altruism that would have to be carried out with tough-love, including war. The first stanza goes:

Take up the White Man's burden, Send forth the best ye breed

Go bind your sons to exile To serve your captives’ need;

To wait in heavy harness,

On fluttered folk and wild – Your new-caught, sullen peoples,

Half-devil and half-child.

It is hard not to notice that women have heretofore been described as the slaves of lust and symbols of demonic disorder, and that they have also been described as children. In either case, the “half-devil half-child” requires containment and tutelage . . . from men, “real men.”

The term Mies uses for to describe how colonies and women are conflated with an objectified post-enlightenment nature is “defining into nature.”

Mies cites Merchant’s Death of Nature:

Carolyn Merchant has shown that the destruction of nature as a living organism – and the rise of modern science and technology, together with the rise of male scientists as the new high priests – has its close parallel in the violent attack on women during the witch hunt . . . Merchant does not extend her analysis to the relation of the New Men to their colonies. Yet an understanding of this relation is absolutely necessary, because we cannot understand the modern developments, including our present problems, unless we include all those who were ‘defined into nature’ . . . Mother Earth, women, and colonies.

This late-Victorian, reactive masculinity complex was the hothouse for the aggressive militarism epitomized in the public persona of Theodore Roosevelt and the social movement with which he was most closely identified: Progressivism.

Militarism was not an epithet at the dawn of the twentieth century; it was celebrated. Indiana Senator Albert Beveridge, in an editorial for the Los Angeles Times, wrote, “Every generation of Americans has been soldiers. Militarism in America! Yes, indeed there is enough militarism in the blood of the free young men of this republic not only to defeat the world at arms, butt to defeat every military uprising among ourselves that might seek to overthrow the republic. The future of the institutions of the republic is in the hands of the republic’s young men, and in their hands those institutions are secure.” The reference to blood in this case is racial. The jurist and future Secretary of State for Theodore Roosevelt’s presidency, Elihu Root, who was a great proponent of building a modern military in the United States, referred in the same way – to “the blood” – meaning an inhering American (read: Anglo-Saxon) racial superiority – “the American race,” he said.

Several vehicles were employed for the militarization of the United States during the Progressive Era, among the most prominent were public schools, sports, Boy Scouting, and gun culture.

Today, we will just look at scouting, since that is the institution that ignited the question about what was "won" in today's policy reversal by the BSA.

Scouting was strongly encouraged Progressives at the turn of the twentieth century, even though it was also seen as a corrective influence for the potentially feminizing influences of the school classroom where militarism was being indoctrinated using the Prussian public school model.

Allen Warren writes that scouting was understood to promote the personality of a combination of “military scout, trapper, and colonial frontiersman.” Robert Baden-Powell – the guru of the scouting movement – believed that schools were remiss in their concentration on literacy and the classics, which, after all, might be mastered by girls as well as boys. He wanted to build men, and a particular kind of man at that. Baden-Powell even decried football, a favorite sport of Roosevelt's . . . not participation in it, but the fact that urban male youth were hanging out around the matches, where they slouched and smoked cigarettes.

Roosevelt himself pointed out that industrial civilization had some downsides, and praised scouting as an activity that would build men who were “good soldiers and good citizens.”

Not everyone was overwhelmed with enthusiasm for Progressive masculinity, Roosevelt’s male posturing, or scouting. Members of the burgeoning socialist movement and the Industrial Workers of the World were quick to point out that there was an authoritarian edge to these developments that might be used against the labor movement. The Western Federation of Miners issued a statement that said scouting was designed for “an effective of servile, dog-like automats . . . a trained body of flunkies, strikebreakers, and in case of need, policemen and soldiers.” In fact, the Boy Scouts were used on various occasions for strikebreaking, and some unions threatened to expel anyone who allowed their boys to join, saying the boys were being indoctrinated into “fealty to . . . employers” and that the purpose of scouting was “to capture the minds . . . of children for the military state.”

Churches now routinely support scouting as a character-building activity, with little thought about its origins, its goals, or its inhering militarism. Boy Scouts trained members in shooting, as well; and today there are still merit badges awarded for rifle and shotgun shooting.

In 1912, one scout shot another with a rifle, and there was a temporary discontinuation of the “marksmanship” badge, but lobbying from the National Rifle Association (NRA) got the merit badge reinstated in 1914.

The BSA today works closely with the NRA on its shooting program. These kids are all dressed in uniforms, practice military drill and ceremony, are schooled in hyper-nationalism. Seems pretty militaristic to me. But if you overlook this history of the BSA and the subtexts of all it promotes in the formation of "masculinity," then today's shift is real progress.

Thank goodness, now even those boys who are encouraged to be sexually abstinent but at the same time are assumed to have a "homosexual" orientation can subject themselves to paramilitary formation, national boosterism, and mindless conformity to the norms of white masculine America.

It's the Big Tent. The system is at a point, now, where it needs all the help it can get----from any quarter (like Army recruits with a violent criminal background, f'rinstance). You can be anything you want, as a "lifestyle choice", just pledge loyalty & fealty to the system above all else. It's down to the bone, now.

ReplyDeleteThis. Is. Sparta. But seriously, boys and men, I enjoyed the hard data here.

ReplyDeleteGrowing up too poor and rural, Boy Scouts were not even an option for me. I formed my relationships with nature outside of all that, and I’ve come to see that time spent either alone or with a friend in wild places has largely defined the trajectory of my life. It is a damn shame that fom many urban kids, the BSA will be their first and possibly best opportunity to get into truly wild places.

ReplyDeleteI appreciate this analysis Stan. Quite a lot of my working life has been spent trying to offer young people an alternative to the Boy Scouts, for all the reasons you point out. When I was about 16 years old, I volunteered with a non-profit that put on a summer camp for developmentally disabled folks. It was one of the best experiences of my life. A BSA camp graciously loaned us the use of one of their camps to facilitate our own and I soon found that to always re-affirm our own identity, it was tradition for our male staff to attend camp dances in drag.

Despite our obvious differences with the BSA , they saw our good work and decided that they’d try to co-opt us, using our reliance on the features of their facilities, (close proximity to the folks who attended the camp, wheel chair accessible paths, showers, etc., etc.) as leverage to get us to remake ourselves in their image. Apparently, they didn’t yet have a “works with the disabled badge” and this was a perfect opportunity for them to show everyone how big hearted they were.

For our unwillingness to be absorbed into the BSA, the camp dissolved and nothing like it in that community emerged.

I recently jumped back into climbing and saw a wood block print from one of my climbing/artist heroes on a T Shirt (his work also illustrates the book Into Thin Air, which coincidentally enough is the story of the compromise of ideals and some the tragic consequences that follow). It reminded me of one of his prints that always moved me. It is the image a lone, ropeless climber, head hung low in agonizing struggle, axes dug into the ice, and below brick buildings rise in the night among factory smokestacks. To me, it always represented the individual struggle to find meaning through pain and toil in the wild in total rebellion of the enslavement of industrialized society. I’d first seen the print in one of the artist’s partner’s books, a book that gives a loud and sure voice to this rebellious, uncompromising, spirit. I was shocked to learn that after this author retired from the dangers of extreme alpinism, he went to work for the DOD, training special operations forces in climbing, crisis nutrition, going so far as to design their mountain warfare gear, and even designing physical fitness regimes to help National Guard personnel stay in shape.

I commented on the contradiction I found in this to one of my climbing partners, with who’d I’d worked as a climbing guide for on outdoor education non-profit (that remains a wonderful alternative to BSA). In that circle, the core staff members had studied at Tom Brown’s Tracker School, where they’d learned all of their Native American based survival and tracking skills that they passed on to children. My friend told me that even Tom Brown had taught his skills to special operations soldiers. Later at a bookstore, I flipped open a military survival manual (U.S. Army I think) and the illustrations looked like they came straight from Tom’s field guides.

At the wilderness preserve I work at, we host dozens of scout groups a year. The troops usually appear to be led by fathers who are overworked, underpaid, out of shape types trying to wrangle boys who live much of their lives in videogames and public school. It is hard not to take pity on them. It is a terribly difficult job, especially since their educational conventions are based so largely on conformity and not on individual creativity. I usually end up praying that the chance to be outside will outweigh the all the BSA indoctrination. In the end, I’ll never know.

http://truth-out.org/opinion/item/21624-military-metaphysics-how-militarism-mangles-the-mind

ReplyDelete"Most institutions have a propensity to promote mediocrities, those whose primary strengths are knowing where power lies, being subservient and obsequious to the centers of power and never letting morality get in the way of one’s career. The military is the worst in this respect. In the military, whether at the Paris Island boot camp or West Point, you are trained not to think but to obey. What amazes me about the military is how stupid and bovine its senior officers are. Those with brains and the willingness to use them seem to be pushed out long before they can rise to the senior-officer ranks. The many Army generals I met over the years not only lacked the most rudimentary creativity and independence of thought but nearly always saw the press, as well as an informed public, as impinging on their love of order, regimentation, unwavering obedience to authority and single-minded use of force to solve complex problems."

It is clearly an act of parliment that this documentation called an officer effeciency report shares the same initials as Otto Ernst Remer.

ReplyDelete