The following is an excerpt from Borderline - Reflections on War, Sex, and Church, which I am publishing through Cascade Books, probably in January, February at the latest. It is not a direct response to the torture debate that has arisen in response to the release of some information about U.S. agencies using torture against various detainees. This excerpt will not answer many of the questions raised by that debate, which is - to the chagrin of myself and others, Christians - a debate among putative Christians in the United States. More to the point, there is a majority among American Christians who believe there are circumstances that justify the use of torture against people who are held captive. Everything I know about the teachings and example of Jesus tells me that torture is altogether evil.

I know all the trumped-up consequentialist hypotheticals... heard them all trotted out during every debate about this. Greater good, blah blah blah. These come from a culture that has been indoctrinated by television and film, with cardboard characters, and good guys who never suffer any consequences - no even a bad conscience, or the desire to get that rush again - when they hurt, maim, and kill bad guys. It is simple-minded culture, conformed by relentless conditioning through what Chris Hedges has insightfully described as "electronic hallucinations." They are pumped into living rooms, a manufactured "outside world" framed for the flat screen. I don't know how much light this partial chapter will shed on the topic, but here it is, for what it is worth... one of those stories that teach us to love torture. And some of the gendered conventions that are hiding under the surface.

Charles Taylor

describes a “social imaginary” as “broader and deeper than the intellectual

schemes people may entertain when they think about social reality in a

disengaged mode.”

This has to do with not only notions of sociability beyond immediate

experience, but also with how things “fit together” in both a normative and

moral sense.

On September 24,

2004, CNN reported charges brought against three U.S. Navy SEALs in the death

of an Iraqi detainee,

part of a much larger damage control investigation in the wake of the Abu

Ghraib photo crisis, an investigation that quietly expanded to 222 abuse cases,

fifty-four of which had resulted in detainee deaths. This

particular set of charges managed to push the story back into the media because

of the involvement of SEALs, who, like all Special Operations troops, are

masculine national icons.

In that same

month, my 18-year-old son brought home a video-store DVD of the Denzel

Washington hit, Man on Fire. I generally avoid watching films that

feature guns and fireballs on the posters, but on this particular day, there were

three-hours to kill, and it was an opportunity to do something with my son that he wanted to do, even if it was

just catching a movie.

Man on Fire is

well-written, expertly acted, skillfully directed, and edgily edited with

plenty of whip-pans and jump-cuts for the MTV generation. Denzel Washington’s

character, a Special Operations veteran struggling with anesthetic alcoholism

and the grim memories of his imperial adventures, is drawn into a complex

Mexican kidnapping scheme as the bodyguard for a terminally intelligent and

charming little girl, an American expat child named Pita living in dark and

dangerous Mexico City with her extremely attractive parents, a Americanized

Mexican father and an American mother.

Man on Fire’s begins with

that favored escapist film convention in the United States, the salt ‘n’ peppa

buddy-team, always reassuring to America in its stubborn denial of our still-racialized

reality. Washington is a black actor who has consistently strong crossover

appeal with white audiences. In an early reveal-scene, Washington (Creasy)

appears with his white former special-ops colleague, a dissipated but likeable

expatriate himself, Rayburn, played by Christopher Walken. Rayburn is portrayed

as sympathetic even though he is backgrounded by bikini-clad, nubile young

women somewhere in Latinoamérica, the expat with some money taking

advantage of the favorable exchange rates. Washington’s character, Creasy, asks

Rayburn, “Do you think God will ever forgive us for what we’ve done?”

Rayburn replies,

simply, “No.”

As this exchange

suggests, a pseudo-Christianity is integrated into the theme and the plot throughout

the film, including a story of redemption. However, Man on Fire is really a sly male-revenge-fantasy. The question

about God’s forgiveness and the fact that Creasy carries, reads, and commits to

memory portions of his Bible (which the cosmopolitan Creasy quotes in Spanish

to a Mexican nun, before telling her he is a “lost sheep”) are combined with a

hypnotic and elegiac background score that clearly makes Hollywood-God the

film’s main invisible character. There is an almost easy-going character

development in the first half of the film that draws the audience emotionally into

Creasy’s guilt and pain. God intervenes with an epiphany for Creasy when Creasy

attempts suicide with his pistol and the bullet fails to fire. Drunk and crying

in the pouring night rain with his favorite song, Linda Ronstadt’s Blue

Bayou wailing away (I told you this film is blatantly manipulative), Creasy

calls his friend, Rayburn, and asks what it means when a bullet fails to fire .

. . not letting on that he has attempted to blow his own head off.

Rayburn knows intuitively,

of course, and he shares some Hollywood-concocted special-ops lore that “a

bullet never lies.” This is Creasy’s Dama-scene, his conversion, whereupon he gives

up the booze and becomes fair Pita’s surrogate father, even as her own

treacherous (Mexican) father plots to have her kidnapped for the insurance (he

will die by the same truthful bullet later in the film).

Act II is Creasy

and the child falling into filial love, whereupon Pita is kidnapped. Creasy is

gravely wounded in a heroic attempt to foil the sequestration, the plan goes

sour, and Pita is killed. This is the cue for Creasy to become the instrument

of God’s justice, of course, and even before he is mended from his ever more

Christ-like and manly wounds, he begins to hunt down, systematically (and even sexually)

torture, then exterminate every participant in the kidnapping and ostensible

murder of fair Pita. The audience is carried along via its well-massaged

emotions, and we are invited to wallow in the vengeful cruelty of Creasy cutting

off a crooked Mexican cop’s fingers with pruning shears as part of an

interrogation, and other graphic cruelties.

In the key

revenge scene for the entire film, Creasy captures and renders unconscious one

of the evil Mexican co-conspirators.

When the bad guy awakens, Creasy tells him that his rectum is packed

with explosives for which Creasy holds the remote detonator. In other words,

Creasy has penetrated his victim, anally raped him, topped him, feminized him

by making him his “bitch.”

Comparisons to the

frequent celebration of prison rape as an instrument of revenge are

irresistible here. Creasy shows an utter lack of empathy, while the captured

and violated bad guy shudders and weeps (“cries like a little bitch”) in his

terror. The audience is invited to share in Creasy’s sadistic enjoyment of the captive’s suffering. In

the climactic end to this scene (pun totally intended), as Creasy walks away,

leaving the captive cuffed to a car in the background, the explosive detonates

behind our hero—a fiery and sexually symbolic shock and awe—a blazing,

gasoline-powered “money-shot.”

In a fine

imperial flourish, the honest but ineffectual Mexican police stand aside while

the American warrior Creasy delivers God’s justice in a lethal wave of violent

masculine revenge-energy, until the denouement when Creasy, now Christ-like,

walks willingly to his death in exchange for Pita (who it turns out is alive

after all), telling her he is going “home to Blue Bayou.” Creasy, who believed

he could not be forgiven by God, instead serves as God’s instrument of war and is

redeemed.

Rosemary

Hennessey writes:

As one of the most pervasive forms of cultural narrative in industrialized societies, commercial film serves as an extremely powerful vehicle of myth. The mythic status of Hollywood films is of course enabled and buttressed by corporate endorsement and financial backing for distribution and promotion. To some extent the scripts that do get picked up manage to be supported because they already articulate a culture’s social imaginary—the prevailing images a society needs to project about itself in order to maintain certain features of its organization.

Film

participates in meaning-making, and the audience participates in the film.

Linda Kintz renames the social imaginary the “national popular . . . based not

on content but effects.” We

recognize and embrace the formula for male revenge fantasy, one of the most

popular film genres, the theme of which is

redemption through violence. Creasy redeems himself and the situation, and earns

God’s forgiveness, in a bloodbath. But it is more. Go back to that scene, that

anal rape by explosives, and see again that sex and violence are understood to

have interchangeable meanings. See, again, the meaning of sexually receptive

(woman) as conquered.

##

I stumbled onto

a radio program in 1999, called “Lockup.” It

was about prison. The third act was called, “Who’s your Daddy?” It was a

reading from ex-con Stephen Donaldson’s pamphlet telling new convicts how to

survive in prison by protective sexual pairing. The description of this segment

reads:

Who’s Your Daddy? A reading of a pamphlet written by ex-con Stephen Donaldson for heterosexual men who are about to enter prison, about how to “hook up” with a stronger man—a “daddy” or “jocker”—who’ll provide protection in return for sex. He explains the rules and mores that govern this part of American prison culture. There’s no graphic language and there are no graphic images in this story, but it does acknowledge the existence of sexual acts. Read by Larry DiStasi.

It was a

matter-of-fact, step-by-step instruction booklet on how the new convict should

shop for a strong man (a jocker, a “top”), and how to manage the relationship

with him (as the “catcher”, or bottom), the men’s prison version of how to get

the right husband. A very animated online discussion followed.

One comment: “memo

to myself: don’t go to prison”

Another comment: “Disturbing article. I’m not into constantly losing fights only to get raped at the end. And no way would I catch for someone. I would either become a jocker, or stay in solitary. Unbelievable—what a different world.”

Another comment: “Disturbing article. I’m not into constantly losing fights only to get raped at the end. And no way would I catch for someone. I would either become a jocker, or stay in solitary. Unbelievable—what a different world.”

More: “Oh. My.

God. Its [sic] one thing to joke about ‘Federal

Pound-Me-In-The-Ass Prison,’ but this article’s matter-of-fact presentation

exposes the horror. Can’t prison authorities do something about this? Like

maybe investigate and prosecute all rapes?”

And this: “Wow.

The section at the end on Adaptation was really interesting. It must be

completely world-altering to start out a jail-sentence straight and then slowly

have your identity punk’d. Reading stuff like this reminds me of the kind of

horrific practices that happened in previous centuries of human history and in

animal tribes. Not much has changed, in some ways.”

Finally (this

one caused some to get angry): “Ah yes, there’s nothing to get red-blooded men

fired up about rape than a good ol’ drop-the-soap-story. By the way, it happens

to a woman about once every 2 minutes, according to the DOJ.”

This is how

difference is constructed as sexual hierarchy, what women’s oppression is, a

system of oppressive social power and shows how when there is no “difference,” we

construct difference sexually (you

get to be the “wife,” the punk) in order to construct

the hierarchy. In this case, the instruction booklet is not talking about

“rape,” as we define it around the legal category of consent, but how to avoid

“rape” by consenting to receptive sex with one powerful man. Legally speaking,

the prisoner who accepts one jocker for protection is engaged in “consensual”

sex. This is one way that men might understand what it is like to be women, how

rape as a constant threat for modern women serves as one form of pressure for women

to accept the perennial sexual-contract: protection in exchange for obedience. It

is not new. Article 213 of the Napoleonic Code (1804) stated, “the man owes the

wife protection, she owes him obedience.”

But the imagination of prison rape (and prison “consent”) might make it real

for men. Men who have been raped do not have to imagine it. For those who

haven’t, maybe this example will help them “see

this woman.”

In the online comments

afterward, men tried to find anything

to make this different than what happens to women; “women are not locked up by

the state”; “rape doesn’t generally happen in the ass”; and so forth. The

avoidance is visceral, desperate. I can’t

be a “catcher!” We have to stop prison

rape . . . oh yeah, and all other rape, too (as an afterthought). This is a kind

of microcosm of women’s condition, and for the so-called instant of “consent,”

because it is not metaphorical; it is

real, and it is happening to men, and

that makes it suddenly an urgent

issue.

How do we now

parlay that outrage into an understanding that this is what some of those

feminists are saying about “sex”? They are not talking about equal pay or equal

access to the levers of power, but about the sexual subjugation of women-as-women

by men-as-men. This is how rape and battering and the renting of Indian women’s

wombs as surrogate mothers and international sex-trafficking and the explosion

of misogynistic internet pornography are related. They don’t happen to women

because women are the same as men. They happen to women because they are women.

If we want to

get to the root of homophobia, then we have to understand that it is

underwritten by the devaluation of women. The policing of what Adrienne Rich

called “compulsory heterosexuality” is the enforcement of a gender regime that

is defined by the devaluation of women.

And while there are biblical references to same-sex unions, the idea of

“heterosexual” versus “homosexual” is distinctly modern, an artifact of the

modern propensity, during successive destabilizations of gender, to define

masculinity specifically as being not-woman.

Neither term, heterosexuality or homosexuality, even appears in the

language until 1890.

What does it

tell us that men’s most terrified reaction to the idea of prison is the fear

that women experience all the time? What does it tell us that the worst

punishment is to be made like a woman,

a “catcher.”

Women’s choices cannot

be reduced to the fear of rape (though men can never know how this possibility

haunts the thoughts of women, except perhaps when men face prison); but that

power and comparative powerlessness (the lack of desirable choices) makes the

world of women and the world of men different. We know it is different because we can participate happily in Creasy’s

symbolic rape of the “bad guy,” where violence is redemptive as well as sexual; and if we were to

show the same scene with a woman as the victim of Creasy’s vengeance it would

take on a wholly different meaning. Part of the bad guy’s punishment was to be

made receptive, to be made like a woman.

Creasy was the man,

the conquerer, the jocker.

##

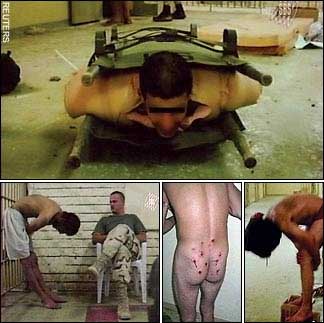

In the

blood-stained prison cells of Abu Ghraib, the prisoners were “softened up” by

feminizing them, by placing panties over their heads, by forcing their faces

into one another’s crotches, by having them placed on a leash in the hands of

an honorary-male woman who was herself sexually partnered with a dominating and

sadistic prison guard. As with the Forest Troop baboons, cruelty was passed

down through the hierarchy.

You can tune

into Law and Order reruns and hear

your favorite protagonist tell the so-called perps (there is that dehumanization prior to control!) that “I’m

gonna make you my bitch,” or smiling as they warn the bad guy that he is about

to go to prison where he will be someone’s “bitch.”

In 2004, when I

watched Man on Fire with my son and

when Navy SEALs were investigated for torture, rape, and murder, the United

States was still freshly traumatized by September 11, 2001, and being fed

militarism in large doses, including and especially our national pastime of

soldier-worship.

“A bullet never lies,” is the emotionally

resonant wisdom of a divinely sanctioned male death cult (manufactured on the laptop of a scriptwriter)

who is not feeding the culture but interacting with it as it acquiesces

to, nay, feeds into and relishes male violence. In a sense, then, Man on

Fire was the cultural recoding of precisely the rationale deployed within the

American culture as the troops were deployed into Afghanistan and Iraq: a

mission, sanctioned by God to deliver his retributive justice, that rationalizes

the suspension of ineffectual law in favor of raw masculine violence against

the caricatures of Evil, and that might require that we commit torture and even

murder to serve a higher call for justice and order.

Creasy,

disguised as a black man to divert us from the fascistic content of this film,

is the strong, violent father: a constant in the emotional cosmos of Mussolini,

of Franco, of Hitler. So we needn’t be shocked when we heard that SEALs were

committing torture and even murder. Nor should we have been taken aback when we

discovered that by the end of 2004 there were dozens of these cases that were no

longer worthy of even page 10. The same cultural interaction that combines

producer and viewer as participants in the meaning-making of male revenge

fantasy films signals to “journalists,” via our shared social imaginary, what

is and is not appropriate. If the story cannot be mapped onto the symbolic and emotional

terrain of providential America, then it is not done at all. It is disappeared

or spun as an aberration from our God-given destiny as bearers of the light to

the deviant brown people of the world. That Denzel Washington is himself brown

not only does not change this message, it gives it Americo-mythic “melting pot”

cover. Washington’s character is a color decoy. His targets were the other brown savages, people on the other

side of the defensive perimeter. We can shift this symbolism to accommodate new

contingencies. It was a rabbi in North Carolina who told me once, “Arabs have

become the West’s new Jews.”

In reality, Special Operations units have fewer African Americans than

any other units in the military, but we need all the myths in a world-view basket,

and Hollywood accommodates: Imperial myths, melting pot myths, and hegemonic

military masculinity myths, to “articulate a culture’s social imaginary—the prevailing

images a society needs to project about itself in order to maintain certain

features of its organization.”

The reality, in

those places where the real military is obliged to do the real “wet work,” in

the prisons and torture rooms, is that they are needed to terrify the

inconvenient population into submission, a reality not suitable for Hollywood.

Without the myths, without Denzel’s tragic pose and truthful bullets and his

willingness to saw the fingers off of Mexicans to get the information on time

to protect the innocent from Evil, how are we to co-sign for Abu Ghraib, for

“rendition,” for “enhanced interrogation techniques”?

We aren’t even

seeing the real victims any longer; the corpses on ice while the young GI leers

over the lifeless face, the naked bodies piled on one another, the hooded men

hung by their handcuffs. Thousands of horrific new photographs were repressed, and

instead we get Man on Fire, redeeming himself before God with unspeakable

violence. Mike Davis calls this intentional denial “ostrich-consensus.”

By the way, the fellow on the box, with the hood on his head, and the wires on his hands, is an Iraqi professor of theology, Ali Shalal. He testified at a Malaysian tribunal (not sponsored by the UN, thus powerless) that all relatively unknown individuals tortured at Abu Ghraib by US personnel were assassinated upon release. His testimony is briefly discussed in Justice Belied (a book on the US/Rwandan state security mechanism, ICTR).

ReplyDeleteSome years ago you asked for a photo, when I didn't have a camera. Here you go (BTom...)

http://gravatar.com/saskydisc

PS any blogs connected to my name have been untended for several years, but I do occasionally check this email.

This is familiar turf in our neverending conversation, Stan... so I have little more to add (maybe a footnote to my own musings on "trophy pictures" and the Warrior/Hunter face of probative masculinity). The only new thought that popped up this evening was about the plot mechanism at the end of Man On Fire, in which the Denzel Washington character accepts a suicide mission, i.e. kills himself. In the fictional context there's an ostensible motivation (his death will pay for the child's life). But if we take a simplified view of the plot it looks rather horribly familiar: man is enraged by events beyond his control, seeks vengeance, hurts and kills numerous people, then kills himself.

ReplyDeleteSounds like yet another "school shooter" (a phrase that didn't even exist when I was in school). Sounds like a pattern, a strategy, that young men are learning as they worship their TVs, movie screens and game boxen. Sounds a little like the career arc of a number of young soldiers. Do a lot of killing and then kill yourself (offing your spouse and family is optional, I guess).

It's almost an Anton LaVey-style satanic parody of the life and death of Christ. I think it's being *sold* as some kind of heretical substitute for the life and death of Christ. It's only a vague feeling I'm having, but I think the basic script of "redemptive" extreme male violence followed by suicide is being acted out all around us, in different contexts.