Jot that down. Another excellent example of how the radical medical monopoly - with psychiatrists now as our priests - uses naming to achieve its power. An improvement, we might suppose, over the Adonis complex, what this so-called personal "disorder" used to be named in our post-Freudian period. At least the language of the psychiatrists has made space for the non-Adonis women who exhibit the same behaviors described for men in this diagnosis.

But the pathology is not individual. It is cultural; and this complex or disorder is, in fact, a symptom of that cultural pathology, this indeed very sick social order.

The original use for treadmills was to employ the muscle-power of prisoners to run machines. Now we pay for the privilege of mounting them. I won't overstretch this as a metaphor, tempting as it may be. I readily admit that de-skilling and technological development have compelled us to spend long stretches of time on our asses, to the point where actually doing things with our bodies - swimming laps, chugging on the treadmill with our earbuds blasting old Kinks tunes, pumping iron, and so on - feel pretty good. We are made to exercise, and when we don't do things with out bodies in the course of making our way, that treadmill sweat can feel like a relief.

Therein is part of that social pathology - our division of labor, our specialization. But I am not referring to, nor is this psych appropriation of the phenomenon, this adaptation to specialization and seatedness though scheduled exercise. I am referring to that mad preoccupation with what we look like combined, with captivity to the obsession for wrestler-like muscles.

This actually has its roots in "muscular Christianity." Here is a short excerpt from Borderline:

Western “civilization” after the enlightenment developed through the conquest of colonies. American expansion after the Civil War was driven by a war against indigenous people until the Spanish-American War, whereupon the United States began expanding its extra-continental colonies through inter-imperial war. The normative/ideal Western male was defied by his separateness, by boundaries separating him from women, from nature, and from the “unwashed masses” of conquered colonies. He was unlike any of these, and yet he was obliged to transgress those boundaries in order to subdue women, nature, and colonies. Women were domesticated. Nature was tamed. Colonies were disciplined for extraction.

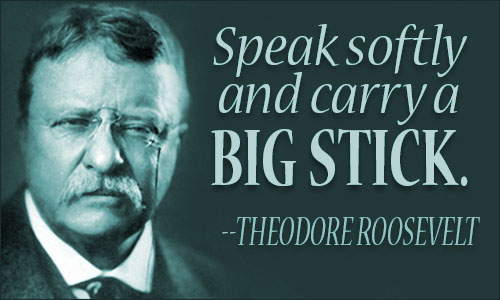

By the Victorian period in the latter part of the nineteenth century, anxious and influential men like the founders of “muscular Christianity” began to describe a “crisis of masculinity” for “white” men based on a surfeit of gentility and migration to the “soft life” of the cities. One of the most vocal of these critics would become the president of the United States: Theodore Roosevelt. Roosevelt was an emblematic leader when “a fear about the softness of American society raised doubts about the capacity of the United States to carry out its imperial destiny.”8 Continental expansion had ceased, and with it the basis of the national myth of frontier masculinity. There was a fear that the loss of masculinity constructed as conquest would lead to national impotence. Churches spread this fear as well, along with the fear that urban life would bring about a “moral softening.” Immigration had increased, and this discourse included talk about “race suicide.”9

Imperialism was embraced as Manifest destiny, as the Christianization and civilization of the dark others and the means for the reclamation of white masculinity. Roosevelt rebuked American opposition to the bloody occupation of the Philippines:

"I have scant patience with those who fear to undertake the task of governing the Philippines . . . [who] shrink from it because of the expense and trouble; but I have even scanter patience with those who make a pretense of humanitarianism to hide and cover their timidity, and who cant about 'liberty' and 'the consent of the governed' in order to excuse themselves from their unwillingness to play the part of men. Their doctrine, if carried out, would make it incumbent upon us to leave the Apaches of Arizona to work out their own salvation, and to decline to interfere with a single Indian reservation. Their doctrines condemn your forefathers and mine for ever having settled in these United States."10

Racial superiority discourse was not new, but by the turn of the century it had taken on a distinctly Darwinian idiom.11 Muscular Christianity explicitly embraced the narrative of white supremacy based on this amalgam of “science,” Manifest destiny, and martial masculinity, calling this amalgam “natural theology.”12 Just as American Protestantism had urged its communicants to financial success as a sign of God’s providence, men felt compelled to live into an idea of fit-ness. Muscular Christianity was literally about muscles inasmuch as it promoted something then called “physical culture,” the progenitor of bodybuilding and today’s media-hyped Adonis complex among males.

Lampooned by social critics like Sinclair Lewis and H. L. Mencken, muscular Christianity achieved a foothold in American culture among the influential and contributed substantially to turn-of-the-century militarism.13 Fashion and other commodity-promotion phenomena had introduced the manufactured preoccupations of women into the public sphere, that is, the marketplace, where women’s “influence” was perceived as a threat, especially to impressionable urban boys.

In the novel Tom Brown at Oxford (1861), Thomas Hughes, one of the founding fathers of “muscular Christianity,” wrote that it is “a good thing to have strong and well exercised bodies. . . . The least of the muscular Christians has hold of the old chivalrous and Christian belief, that a man’s body is given him to be trained and brought into subjection, and then used for the protection of the weak, the advancement of all righteous causes, and the subduing of the earth which God has given to the children of men.”14 Theodore Roosevelt said that the book should be mandatory reading for Americans. (pp. 274-75)

I'm gonna do some bicep curls now. (-:

No comments:

Post a Comment