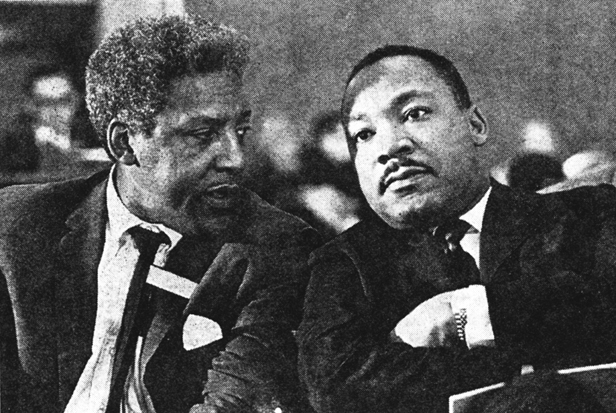

“Call it democracy, or call it democratic socialism, but there must be a better distribution of wealth within this country for all God’s children.”

– Dr. Martin Luther King, Jr. to the Negro American Labor Council, 1961

The campaign by Vermont Senator Bernie Sanders, self-declared "democratic socialist," for the US Presidency has confronted us with the question, 'What is socialism?' This is a controversial question, as is the question, 'What is a Christian?' That controversy inheres not only in the implicit demand of a question like this for a simple answer, but also in the many tendencies and traditions and tensions among those who call themselves 'socialist,' or 'Christian'; and the same thing could be said of 'feminism,' or even of that subset of socialists who call themselves Marxists. There is, in fact, no definitive answer to this question (for whichever category) that does not require a lengthy explication - one that digs down into history and philosophy. Since we in the age of facebook and twitter, and before that, the age of television, have been formed by the short answer, the one-hour resolution, the 30-second commercial, the art of manipulative 'messaging,' the bumper sticker, and the soundbyte, we are disinclined to spend time seeking these answers in depth. Since we almost always approach every question with a pre-existing personal, cultural, or political agenda, we are also always in danger of confirmation bias.

One of the reasons I use this blog is because I like facebook. I like the way it allows me to keep in touch with loved ones; I like my virtual friends; I like the way people can exchange articles and humor and beauty. And I like reasoned, civil debate. But there are certain topics, like this one, that come up again and again, and do not fit well in the facebook format. Rather than slog through the inevitable tit-for-tat, or risk the kind of misunderstandings that can poison textual exchanges, I can do a blog piece that explains my own thinking in detail (giving anyone who cares to read it time to reflect and question and rebut), then post it as a link. I use other people's blog posts the same way.

The current campaign has generated a froth of talk about 'socialism' (and if Sanders wins the nomination, there will be a great deal more), most of it in one way or another wrong. This is apparent not just in the general population, but among Christians, because the wrong-ness of these inaccuracies, simplifications, and reductions growing out of the residual anti-communism of American culture generally. So before we begin to unpack these issues, a few plain statements of fact seem necessary as a preface: All socialists are not communists. There are more than one kind of communist. There are more than one kind of socialist. Everyone in power who calls themselves either communist or socialist is not necessarily what they say they are. The putative socialist heads of Europe are acting in complete concert with neoliberal capitalism, as are the putative communists of countries like China and Vietnam.

Enzo Traverso, an Italian historian, has a new book (new in English, 2007 in Italian), Fire and Blood - The European Civil War: 1914-1945. Do that double take. Now you see it. He is calling World War I and World War II, including the interwar years, one single and uninterrupted conflict: a European Civil War (and he is not the first). This premise and his conclusion are well worth the effort to read the book; but I'd like to selectively engage with it from a different perspective. Traverso is an Italian Marxist. But I have found passage after passage in Traverso's book that connect directly to the book I wrote about war, as a Christian.

I'll come back to Traverso's book by and by. I want to have an imaginary conversation between a certain range of socialists and a certain subset of Christians that aims first at reaching out to one another in a search for common ground.

Given that the political contender to the White House with the most momentum describes himself as democratically socialist - this is a really good opportunity for a conversation that started in the sixties and seventies, then went on hold, to be continued. The great campaign that ended legal racialized segregation in the United States was a coalition between Christians (many of them black) and socialists (disproportionately, but not exclusively white). Among our neighbors in Latin America, there was a whole generation of Catholics who carried out a public dialogue and joint social actions with various Marxists. Among Christians, there are those who identify as Christian and socialist: Barth comes to mind. Dorothy Day was an anarchist. There is actually a pretty long list of Christian socialists, more still when we count Amish and other small, self-governing agricultural communities (which resemble agrarian socialism).

Socialism can - like Christianity - be reduced dogmatically to a set of propositions to which we must consent to remain within the circle of trust. Or socialism - like Christianity - has been manifest in communities of action that have confronted injustice and sought remedies for the kinds of suffering that are bound up with the apparatuses of power. In the case of reduction to proposition, many socialists and Christians will consistently disagree. Alasdair MacIntyre, in describing the early influence of Marxism on him, then the influence of his subsequent Thomist convictions, quipped: "The only thing Marxists and Thomists agree on is that Marxism and Thomism are incompatible." In the second case, however, in confronting injustice, even though the socialist (and not just Marxian socialists, there are others) and the Christian may be standing on different metaphysical ground, but they are co-located in Newtonian time-space, and in their purpose.

If anything will rupture relations between socialist and Christians (again, recognizing that there are a few of us who would claim both), it will be diversion from that common purpose into in-resolvable debates about the correct set of intellectual propositions to passkey us into that sacred circle of trust. When the premises are incommensurable in a debate, that debate can never be concluded.

Fortunately, there are socialists and Christians who are mature enough to understand when a conversation is a real exchange and when it is a power struggle. Sectarianism is the expression of ideological power struggle - reduced to consent to a set of propositions that open sesames the gate to the inner circle of trust.

One of the things the Sanders campaign is doing right this very moment (and I don't care, I'm sorry, about whether Sanders meets this or that definition of 'socialist') is forcing even the media to speak two words aloud that were previously verboten. Single. Payer. Bernie Sanders will not single-handedly develop the total democratization of Medicare; but a popular movement for it - with an advocate in the White House - might make history. Who knows? But all the socialists that I knew, as well as a good number of Christians I now know, want a single-payer health care system in the United States. It's not a political program; it is a specific campaign for the nationalization and universalization of health care. You don't qualify because you pay a premium. You qualify by breathing. So the practical work might be done together.

I was once an active socialist, one of the Marxist variety, one who shifted my formal allegiances through several leftist organizations. I was a member of the Communist Party USA, then the Committees of Correspondence, then a Haitian political party (long story), and finally Freedom Road Socialist Organization. At the same time, I was a kind of professional activist - on the payroll of a non-profit organization that studied money and politics - and I was involved in union actions, protests against the hog industry, actions on behalf of black farmers, campaigns to end the food tax, environmental justice actions, dozens of conferences, a stint as registered lobbyist to the North Carolina General Assembly; then 9-11 happened, and I became a semi-professional antiwar activist and writer. The money dried up in 2006, and by the end of that year I'd severed all my contacts with campaigns and programs. I began doing manual labor and have continued to do that into the present day.

2006 was a hell of a year. It was the year my writing employer went crazy and took off. Income - zap! It was the year that I made my 21st and last trip to Haiti. It was the year I published Energy War and Sex & War. It was the year that I was lead organizer for the Veterans and Survivors March for Peace and Justice - six days walking from Mobile to New Orleans. It was the year I went on then off of pills for my mental state. It was the year I began working with the Tillman family. It was also the year that I started studying Christianity (within a year of peering into that water, I fell in).

We walked past a ruined schoolyard in New Orleans, six months after the hurricane hit, and there was no government there. It was like that scene from 28 Days Later, when the chagrined survivor of the zombie apocalypse says, "Of course, there's a government! There's always a fuckin' government! They're in a plane or a bunker!" Alas, there in parts of New Orleans, six months post-Katrina, there was no government. But here's the thing. The school was open and running. It was not running according to anyone's regulation books. People from the community cleaned out some space, volunteered to teach what they knew, and the school was re-opened. Not so much as a permit was required. I saw that, and it was like I was shot with a magic glowing werewolf bullet right between the brain slabs.

It was the beginning of the end of my career as a Marxist, and the glide path for my eventual entry into the church.

All the power that simultaneously sustained and disciplined these people was swept off the scene, and they became improvisers. And it set me to thinking about how that power had actually been constituted face to face. Dependency is a big part of power; and institutions go through two watersheds - an Illichian idea. Institutions can sustain and regulate certain practices in ways that are a net gain for institution and society through improvement of the underlying practice; but that's only the first watershed. The second is a result of growth, of difference in quantity transforming itself into a difference of quality. In the second watershed, the institution begins to take itself, as opposed to the good of the practice or of society, as the focus of its efforts, whereupon it becomes counter-productive. It creates more mischief than it corrects.

Some will argue that this is an administrative problem, something that is reparable with regulation. It just requires more oversight, etc. I think it is something much more anthropological. In the second watershed, the institution begins to take itself, as opposed to the good of the practice, as the focus of its efforts; but the problem is not incompetence, neglect, or bad will on the part of individuals. It is a limitation that is etched onto human nature.

“An old friend will help you move. A good friend will help you move a dead body.”-Jim Hayes

Most of our day-to-day interactions involve either primary

or secondary relationships. If you are my twice-a-week hiking buddy, we

have a primary relationship based in mutual care and reciprocal

obligation. If you are my insurance agent or my boss, we have a

secondary relationship based on formal rules. The Dunbar’s number

concept posits that there is a limited number of primary relationships a

person can manage.

One implication of Dunbar’s number is that when we shift from primary to rule-mediated relationships, mutual care is replaced by structural suspicion. This shift is significant. By necessity, a boss, administrator or manager will tend to put systems and rules before care or service. Administrators and managers become the caretakers of impersonality, and that impersonality accrues power to themselves over and against those affected by its practices. This dynamic invariably leads to rules that are designed to serve management at the expense of the managed. In common parlance, “the tail starts to wag the dog.” This dog-waggery leads to resentment towards administration and management, who in turn become defensive, setting up a power struggle in which the administration is already advantaged by the growing dependency of the administered.

What does this have to do with consciously political actions? Well, every time a group of friends considers becoming a committee, we ought to exercise the precautionary principle. Our desire to get bigger, stronger and more efficient can blind us to the more durable strength of mutual-care, which we risk losing by neglecting primary relationships. In other words, if we currently spend 80 percent of our time managing secondary relationships, then we need to figure out how we can flip that to 80 percent of our time nurturing primary relationships. One of the reasons many of us feel powerless in the face of so many crises is that we’re cut off from the social cohesion that can only happen in small, intimate groups. It is not hyperbole to say, then, that management is the enemy of intimate social cohesion, because it substitutes secondary (weak) bonds for primary (strong) ones. By strengthening primary bonds, we not only develop a greater capacity to take effective action on our own behalves; we also increase our capacity to creatively respond to the forces that seem so threatening now.

This was never a factor in the thinking of my Marxist colleagues, though some post-marxists like Robert Jensen have at least begun looking into the ramifications of Dunbar's number. But it undermines the idea of socialism as previously conceived, because it calls into question the kinds of institutional and strategic frameworks that are shared by right and left. We have thought about redistribution and democratic ownership of 'the means of production," but we haven't asked whether any of our failures have inhered in the scale of our organizations. I'll come back to that, too, but this was where I veered away from Marxism, along with two other problems I encountered within both the Marxist tradition and Marxist organizations. Right now, I want to draw a couple of parallels.

Oddly enough, the very same scale-critique that I'm raising about governments (of any kind), about strategic institutions, about practical institutions, and about socialist political programs aimed at gaining more control over the state's apparatuses, I have raised about the church. For my socialist friends who may not be familiar with what "church" means based on popular preconceptions, church, as I am using it here, is a political community. There are struggles within Christianity - as there are within socialism - to determine what church means; but speaking for those of us who represent a kind of generation of Christians who are responding to the pacifist provocations of Stanley Hauerwas, the challenges raised by feminist Christians, and the tectonic shift of the Roman church (my home) on the issue of poverty and climate change, we are a community who proclaims Jesus as sovereign. That is a political claim. There is a whole theology to unpack around that, but the shorthand is that Jesus - who we believe to be consubstantial with God - is "king of kings." This is made even more strange by the fact that this particular king - in earthly life refused to exercise power through violence, refused every position of male authority (father, synagogue official, husband), subverted gender norms, practiced open commensality, and generally speaking exercised 'power' through a terrifying and ultimately fatal vulnerability. Where the church - this is a community of human beings - has strayed from this example, I have noticed three things it has had in common with Marxism: we have valorized an aggressive masculinity (and concomitantly devalued women) , we have embraced violence as redemptive, and we have failed to come to grips with this problem of institutional watersheds and Dunbar's weird little number.

We are teleological - Christians and some socialists. We believe our efforts are aimed at something - some state of being in the future. And both of us are probably able to agree that we are aiming as some kind of peaceable order (even if not everyone agrees that only peaceful means will get us there). The difference between us is that we have entrusted the telos to that otherly-Other, that mind in and out of time and space that preceded the Big Bang, that is, to God. Those somewhat rare Christians - who are also those Christians most likely to show up at some kind of socialist-approved event - are not devotees of progress, as many socialists are, and they do not believe they can or should take power (power that relies on violence) to make history 'come out right.'

We have different languages that overlap. In Marx, we hear about dialectical materialism. Among Christians, you may hear about a dialectic between sin and grace. Theologians and socialists have both bumped into Hegel; but in the socialist tradition, it is Hegel's idea of the dialectic (applied by Hegel to ideas), the constant growth of contradiction and resolution, is divorced by Marx from its idea-centrism (idealism) to material forces (human systems of production). The Christian relationship to Hegel is mixed, but there is a clear connection from Hegel to Kierkegaard (who reacted against Hegel's systemization) to Barth (a dialectical theologian and a socialist) and hence to a goodly number of living theologians. But more importantly, perhaps, pacifist Christians like myself paradoxically agree with Hegel's claim that war makes the state - Hegel saw this as a good thing, while we see it as a problem.

At our best, what socialists and Christians share is a devotion to underdogs. When we were attending large street rallies against xenophobia in North Carolina, where the crowds were ninety percent Latin@, the white and black folks that showed up in support were socialists (of several forms) and Christians (mostly Quakers and Catholic Workers).

Where these alliances were threatened was when either side showed gross ignorance of the other. Socialists don't want to be compared to Stalin; and Christians don't want to be lumped in with Pat Robertson. Neither wants to be associated with Jim Jones - who claimed to be both. This problem is exacerbated by groups or tendencies within each category who claim to be the arbiters of Pure Truth. And both have the same problem: they want to distill this Pure Truth into a set of strict propositions that are the keys to the Circle of Trust.

Socialism is broadly defined as "a political and economic theory of social organization that advocates that the means of production, distribution, and exchange should be owned or regulated by the community as a whole."

Marxism, which can also be broken down into dozens of tendencies, is not synonymous with socialism, and this is important for Christians to understand. If Sanders is nominated, he will be red-baited as a Marxist, because in our abbreviated polemical speech, this suggestion is intended to conjure up images of gulags, show trials, and fifty years worth of Cold War propaganda and its caricatures. Not to put to fine a point on it, this is unadulterated bullshit. Not only is Sanders not a Marxist - as Marxists themselves will be quick to point out - neither Soviet communism nor Chinese communism (which has morphed into neoliberal capitalism) are representative of the thought of most Marxists.

Wikipedia actually has a pretty comprehensive account of socialist diversity, and a whole entry on democratic socialism. That Tony Blair is included is laugh-worthy, because like many European 'socialist' leaders, he is as Thatcherite as the day is long.

One thing I will say, which concerns both socialists and Christians, is that a deeper look into each will reward the student or autodidact with rich, challenging, and nuanced accounts that will expand your thinking. Moreover, as a socialist turned Christian, I see Christianity as the deepest account of all; BUT (and this is to my fellow Christians) speaking of Marxism - as a research methodology - Marxism is ten times more fruitful as a study of history and of current historical processes than any philosophically liberal (this category encompasses both 'liberal' and 'conservative' in our current culture) method. The Marxist method is to study the dynamic relation between our built environment, our institutions, our social relations, and our consciousness, with an eye to understanding power. (There is simply no way to sufficiently apprehend today's society, for example, without an appreciation of 'commodity fetishism,' and I would add to that 'machine fetishism.')

That said, as a Christian influenced by my past with Marxism, by Thomism, by feminism, and by Ivan Illich, I contend that Marxism and liberalism (conservative and liberal) are both the philosophical captives of the post-Enlightenment 'progress narrative,' ergo the term 'progressive,' which has a very checkered past (imperialist, social Darwinist, and eugenicist - that liberals and socialists generally now eschew). It is a disagreement, but it is not a stumbling block to practical solidarity. In fact, most Christians are captives of precisely this narrative, a captivity which I went to great lengths to describe in Borderline.

Even the history of twentieth century authoritarian state socialism requires a good deal of research and reflection to get beyond the simplistic dualisms of popular culture. One thing that I have said for some time - which cannot be explained in three paragraphs or less - is that authoritarian state socialism in the twentieth century developed in every way inside a hostile capitalist world system. This in many respects accounts for its warlike character, treating an entire society as if it is an armed force under martial law, what is sometimes called barracks socialism. Which brings me to one of the key differences I have, as a Christian, with many Marxists. There is still a prevailing belief among most Marxist activists that the socialist transformation of society can and will (teleology) emerge in the wake of revolutionary civil war. Not only do I not believe that; I believe that this form of emergence has a great deal to do with why certain state socialisms became authoritarian. As a Christian, apart from my practical belief that war degrades all its participants (it is never redemptive!), I cannot predicate my own convictions and actions on the existence of an enemy. As Christians, we are commanded to love our enemy - though I readily admit that this is the command most readily and conveniently ignored or tortuously rationalized by Christians themselves. Especially Christian men, who are men first, or nationalists first, and Christians second - because we men, especially we nationalistic men, identify with violence; just as many Marxist men identify with violence. These critiques of martial masculinity were not around during the first half of the twentieth century; and war - horrifying industrialized war - was the cauldron in which twentieth century authoritarian state socialisms were forged.

Just a few days ago, I went to the library and picked up a copy of Fire and Blood - The European Civil War 1914-1945, by Enzo Traverso. I just read it through from cover to cover for the first time. Short review: Read this book.

Written in 2007, it was just released in English this month. What I am finding are some surprising parallels with Borderline in our thoughts about the period between the beginning of World War I and the end of World War II - which Dr. Traverzo has consolidated into one historical event - a single European Civil War.

Traverso is an Italian who writes in French and teaches in English, so

perhaps he is personally very well suited to write a history of

Europe-as-a-whole.

Traverso identifies - as I did in Borderline - Bodin and Hobbes as key figures in both the Enlightenment and in the emergence of the nation-state as modern political sovereign. As a Marxist, he gives a great deal of ink to the French Revolution as a turning point, while I emphasize - as an American and a Christian, the American Civil War as a critical turning point, principally because it was our first industrial war and it was the war that established the state-centric civil religion of the United States that prevails to this day. Traverso, as a European, calls World War I the first 'total war,' while for many reasons - including my own nationality - I said the US Civil War was the first 'total war' - total war being an industrialized war that attacked the civilian civilian population as a morally-rationalized military target.

Traverso also calls modern 'total war' those wars which are fought "between competing visions of the world and models of civilization." Like the twentieth century wars, the US Civil War was fought between two competing visions of social development, which in action meant that the Augustinian principles of 'just war' - long rationalized - were now cast aside in the interest of industrial efficacy.

What Traverso rightly emphasizes is that the Bolshevik Revolution, which would become the strange attractor of international conflict for the rest of the century, did not happen first in Russia. It was a direct outcome of the First World War. Before the war, the Russian peasants who donned uniforms threw their hats into the air in celebration of the upcoming nationalistic adventure. When they returned from the pestilential trenches, shell shocked and disillusioned, they joined the civil war against the Tsar to accomplish the revolution. Little remarked today, the United States was part of a military task force that invaded Russia at the conclusion of WWI on behalf of the White forces. In 1918 Finland, where the population was a mere 3 million, anti-communists killed more than 20,000 Reds in the same year that the Hapsburg Empire was shattered. Most significantly, the revolution spread to Germany, where it was brutally crushed in 1919.

Contrary to Western Cold War attempts to use body counts - real and fabricated - as a way of conflating Communism and fascism, the two social movements that dominated the political landscape after the Great War were Communism and fascism. The body counts were the outcome of mutual militarization, not similarities in ideology.

In Borderline, the interwar period is examined through the literature of the Great Depression, which likewise was preoccupied with the emergence of these two ideological poles, with the emphasis on shifting constructions of masculinity.

War became the arena for the realization of this [heroic] male archetype, transformed into aggressive virility. (Traverso, p. 210)

Leninism, that particular form of socialism that is aimed at capturing state power, is fundamentally warlike. I say that as a former Leninist. And if you go to the most active Leninist discussion site based in the US today (but including voices from around the world), Marxmail, you will find that it is populated by almost exclusively by men. Women show up from time to time, but they are generally and quickly chased off by the aggressive and intimidatingly macho style of argument. The point is, the formation of authoritarian state socialism that developed in the wake of the Bolshevik Revolution was not violent because it was socialism. Many socialists have been committed pacifists. It was violent because it was masculinist, and more to the point, because it was born and developed in a state of perpetual war, 'hot' and 'cold.' World War I, the interwar years, which included the Spanish Civil War (which united Communists, socialists, anarchists, and liberals under the Republican banner against Franco's fascist forces), and World War II. The socialist garrison state was not a unilateral decision by Communist leaders, but in large part an attempt to survive in the face of unremitting hostility.

This is not an excuse. It is a context.

Christians, in particular, should be sensitive to this nuance, because our own institutional past is littered with bodies, for which we find ourselves either repenting or apologizing in the face of the specious critique from professional atheists that 'religion' is the principle wellspring of human violence (The bloodiest human epoch was, in fact, the secular one of the twentieth century). My own central argument in Borderline is that the greatest crimes of the church can be traced to male supremacy as manifested in war and misogyny.

I would ask my fellow Christians, as well as my socialist sister and brothers, to bear this in mind as the election season progresses, especially if Senator Sanders secures the nomination, because if a self-proclaimed socialist stands in opposition to a Republican (a party whose main organizing principle is demonstrably white supremacy, and whose leading candidate now is a dangerously fascist-like nativist), the red-baiting will begin in earnest.

Sanders might be critiqued for a number of things by both Christians and socialists. Many Christians will not agree with his stand on abortion. Many pacifist Christians and socialists will not agree with his support for the so-called war on terrorism, or even his support for the State of Israel. And yet, many of us will agree with his stated intent to mobilize movements in support of single-payer health care, a livable minimum wage, tuition-free college, and public works jobs. In any case, both Christians and socialists are obliged, in my opinion, to dig deeper into these issues than convenient truisms, shortcut accounts of history, and guilt by association fallacies.

And we might use this period to spend more time getting to know each other, because if Sanders wind, the watershed is that the stigma will have been removed from socialism, and we may want to figure out what that means together.

This book responds to the need to revisit or go beyond certain historical controversies of recent decades around the interpretation of fascism, Communism, and the Resistance in order to situate them in a broader perspective, beyond the division into different contexts. It aims also to re-establish a historical perspective against the anachronism so widespread today that projects onto the Europe of the interwar years the categories of our liberal democracy as if these were timeless norms and values. This tendency blithely reduces an age of wars, revolutions and counter-revolutions to the horrors of totalitarianism. The temptation is all the greater, as civil war is precisely a moment in which these norms turn out to be invalid. It has its own logic and its own "laws," which fatally imposed on all the combatants, including those who took up arms to struggle against fascism, to defend or restore democracy. In other words, it is a false perspective to try to analyze with the spectacles of Jürgen Habermas or John Rawls an age that produced Ernst Jünger and Antonio Gramsci, Carl Schmitt and Leon Trotsky. If we see democracy not simply as a set of norms but also as a historical product, we can grasp the genetic link that connects it to an age of civil war. (Fire and Blood, pp. 2-3)In defining 'civil war,' Traverso denies privilege of place to a reductive political science account of civil war, which bases its definition of civil war to something that happens within the boundaries of a nation-state. War is an expression of many forms of social organization, historic, ethnic, environmental, linguistic, et al. But what Traverso emphasizes is what I call (cribbing my late-friend Mark Jones) exterminism. The ever more frequent goal of civil war in the twentieth century was to utterly obliterate one's enemy.

Traverso identifies - as I did in Borderline - Bodin and Hobbes as key figures in both the Enlightenment and in the emergence of the nation-state as modern political sovereign. As a Marxist, he gives a great deal of ink to the French Revolution as a turning point, while I emphasize - as an American and a Christian, the American Civil War as a critical turning point, principally because it was our first industrial war and it was the war that established the state-centric civil religion of the United States that prevails to this day. Traverso, as a European, calls World War I the first 'total war,' while for many reasons - including my own nationality - I said the US Civil War was the first 'total war' - total war being an industrialized war that attacked the civilian civilian population as a morally-rationalized military target.

The Civil War was fought during a period of rapid industrialization. The railroad, the telegraph, aerial reconnaissance balloons, submarines, ironclad ships, rifling of firearms and artillery, and manufactured goods like clothing and equipment—all were introduced together in the American Civil War in a particular way that marks it as the first “modern war.” The Civil War was also our first “total” war, or a war wherein the whole resources of a society are marshaled and the differentiation between civilian and combatant breaks down (civilians had been killed in the past, but the differentiation was still recognized). (Borderline, p. 153)

Total war was not only the matrix of revolution but also that of fascism. Everywhere, political movements were militarized. (Traverso, pp. 53-4)

Traverso also calls modern 'total war' those wars which are fought "between competing visions of the world and models of civilization." Like the twentieth century wars, the US Civil War was fought between two competing visions of social development, which in action meant that the Augustinian principles of 'just war' - long rationalized - were now cast aside in the interest of industrial efficacy.

If the ethos of the sniper evolves into the unmanned drone, the ethos of Sherman, pillaging his way to the sea to rip up the material basis of a society, prefigures “strategic bombing.” (Borderline, p. 166)The mindset of civil war is distinctively different from was as conceived by the fathers of liberalism, Bodin and Hobbes - both of whom theorized out of their own terror in the face of internecine strife. War, in their eyes, was legitimate, but only between states.

Hobbes gave the new philosophy its most enduring political-philosophical basis, shifting the emphasis from Prince to State: “Whereas Machiavelli had been cynical and pragmatic in The Prince, Hobbes was principled and systematic in The Leviathan.”

Hobbes was terrified by the implications of the beheading of King Charles I of England by fanatical Protestants in 1649. The Leviathan was published only two years later (1651). Hobbes described the nation-state; Machiavelli described the actions of princes—the distinction clear between earlier leader-centric politics and a sovereign polity within an administered geographic boundary. (Borderline, p. 123)

In Behemoth, the book Hobbes wrote at an advanced age . . . the English civil war . . . is reduced to a simple act of sedition by an illiterate and brutal mob, ignoring its social and political causes. Its roots lay in disobedience, and Hobbes hastens to add that a prompt suppression would have snuffed out the revolt before it could destroy the monarchy. (Traverso, pp. 200-1)The European Civil War (1914-1945), in common with the American Civil War, then, as the milieu into which authoritarian state socialism emerged, was characterized by a particular kind of brutality associated with the erasure of the enemy's sovereignty. Trotsky wrote, as commander of the Red Army, "The demand for dictatorship results from the intolerable contradictions of the double sovereignty. The transition from one of its forms to the other is accomplished through civil war."

Civil War does not aim at a just peace with a legitimate adversary but rather the destruction of the enemy. At the Casablanca conference, in January 1943 [when Soviet victory in Stalingrad was all but assured, signing the death warrant of Hitler's Reich], Churchill and Roosevelt declared in a joint statement that the allies would not accept any compromise with Germany and Japan, but only their 'unconditional surrender'. It is interesting to observe that in this declaration, which already foreshadowed the tribunals of Nuremberg and Tokyo, the US President and British Prime Minister did not use the conventional formulation of the military lexicon: capitulation. They chose to speak of unconditional surrender, adopting the term that Union forces had imposed on thew Confederacy at the end of the American Civil War . . . In capitulation, soldiers lay down their arms at a public ceremony symbolizing their defeat, but they still belong to the army of a state whose legal existence is still recognized by international law (including by the victor). In unconditional surrender, on the other hand, the defeated army becomes in a way the property of the victor who imposes his domination. (Traverso, p. 75)The logic of civil war, and not socialism, underwrote the brutality of Stalin's bloody forced march to industrialization and his paranoid post-war search for internal enemies, in the same way that it underwrote the Shoah and the use of atomic weapons.

What Traverso rightly emphasizes is that the Bolshevik Revolution, which would become the strange attractor of international conflict for the rest of the century, did not happen first in Russia. It was a direct outcome of the First World War. Before the war, the Russian peasants who donned uniforms threw their hats into the air in celebration of the upcoming nationalistic adventure. When they returned from the pestilential trenches, shell shocked and disillusioned, they joined the civil war against the Tsar to accomplish the revolution. Little remarked today, the United States was part of a military task force that invaded Russia at the conclusion of WWI on behalf of the White forces. In 1918 Finland, where the population was a mere 3 million, anti-communists killed more than 20,000 Reds in the same year that the Hapsburg Empire was shattered. Most significantly, the revolution spread to Germany, where it was brutally crushed in 1919.

Contrary to Western Cold War attempts to use body counts - real and fabricated - as a way of conflating Communism and fascism, the two social movements that dominated the political landscape after the Great War were Communism and fascism. The body counts were the outcome of mutual militarization, not similarities in ideology.

In this historical conjuncture, Communism and fascism alone appeared capable of bringing a solution. There is a striking symmetry between Trotsky's Terrorism and Communism (1920) and Junger's The Worker (1923), likewise between Gramsci's Prison Notebooks (1929-35) and Schmitt's The Concept of the Political (1932). This is not of course a political affinity or similarity of content: Trotsky and Gramsci theorize the emancipation of the proletariat, Junger and Schmitt the end of the age of 'discussion' and the advent of the total state. One side prepares for revolution, the other for counter-revolution. If there is a symmetry between them, it bears on their common roots in the soil of civil war, where they were in merciless confrontation. (Traverso, p. 225).

In Borderline, the interwar period is examined through the literature of the Great Depression, which likewise was preoccupied with the emergence of these two ideological poles, with the emphasis on shifting constructions of masculinity.

In Europe, conditions were sometimes even more dire, especially in postwar Germany, where extracted war reparations left the country in a state of abject despair. The powerful and malignant reply to both 1917 and to the Great depression in Germany was the emergence of a hypermasculine version of racial-national renewal that would come to be known as fascism. By the mid-1930s, the force of this particular version of masculinity would make itself felt in both sympathetic and critical narratives across the Atlantic. Fascism combined its macho hypernationalism, the narratives of progress and eugenics, and a Teutonic mythical nostalgia. (Borderline, pp. 315-6)Traverso, to his credit, also makes reference to gender in his analysis.

War became the arena for the realization of this [heroic] male archetype, transformed into aggressive virility. (Traverso, p. 210)

Germany was inundated with visual propaganda under Hitler—paintings, posters, and statues. Masculinity, as it had been since the eugenics movement began in the West, was closely associated with “physical culture”— bodybuilding. The male form was represented in Nazi art as lean and heavily muscled, modeling its bodily archetypes on Greek and Roman art, with facial features that emphasized “Aryan” beauty. Figures of men were often nude and hairless, emphasizing the idea of a clean, self-contained, impermeable boundary at the skin. The torsos of the Nazi male archetype were modeled on breastplate armor to reinforce the idea of impermeability and lack of vulnerability. Feet were planted firmly apart, hands often doubled into fists, and visages sternly aimed at the horizon.So, in addition to the fact that authoritarian state socialism was a product of war, we can safely say that war is closely associated with another transhistorical, transnational, and transcultural phenomenon: conquest masculinity. Both were in place prior to the Bolshevik Revolution, and yet you seldom here from today's red-baiting opponents of all socialism that authoritarian socialist states were patriarchal.

American war propaganda also emphasized men’s bodies as hardened, using the terms “steely,” “like iron,” and “hard as nails” to describe them. And while Nazi images did the same, they were often hyper-idealized and standing naked to merge a Classical aesthetic with a racial purity ideal. American images had well-muscled men who were dirty, hairy-chested, at least partly clothed, and almost always in contact with big guns or big rounds of artillery ammunition displayed in decidedly phallic ways. The underlying narrative was that of the citizen-solider, the industrial worker cum soldier, of men fused with their machines, with a look of determined anger on their faces. A “now you’ve pissed us off” look. (Borderline, pp. 344-5)

Leninism, that particular form of socialism that is aimed at capturing state power, is fundamentally warlike. I say that as a former Leninist. And if you go to the most active Leninist discussion site based in the US today (but including voices from around the world), Marxmail, you will find that it is populated by almost exclusively by men. Women show up from time to time, but they are generally and quickly chased off by the aggressive and intimidatingly macho style of argument. The point is, the formation of authoritarian state socialism that developed in the wake of the Bolshevik Revolution was not violent because it was socialism. Many socialists have been committed pacifists. It was violent because it was masculinist, and more to the point, because it was born and developed in a state of perpetual war, 'hot' and 'cold.' World War I, the interwar years, which included the Spanish Civil War (which united Communists, socialists, anarchists, and liberals under the Republican banner against Franco's fascist forces), and World War II. The socialist garrison state was not a unilateral decision by Communist leaders, but in large part an attempt to survive in the face of unremitting hostility.

This is not an excuse. It is a context.

Christians, in particular, should be sensitive to this nuance, because our own institutional past is littered with bodies, for which we find ourselves either repenting or apologizing in the face of the specious critique from professional atheists that 'religion' is the principle wellspring of human violence (The bloodiest human epoch was, in fact, the secular one of the twentieth century). My own central argument in Borderline is that the greatest crimes of the church can be traced to male supremacy as manifested in war and misogyny.

Borderline is about two questions. First, why have Christians been so warlike? Second, why do Christian men still caricature, dominate, misrepresent, condescend to, and dismiss women? I am convinced that these two questions must be answered together. in the various reflections that make up this book I hope to make a case for the following claims. Masculinity is very often constructed as domination and violence—direct violence or sublimated and vicarious violence. War is one of the most powerful formative practices in the development of masculinity understood as domination and violence; and recursively, masculinity established as domination and violence reproduces the practice of war. in societies that celebrate war, domination-masculinity is likewise celebrated and becomes a norm to which men, speaking here of males, aspire; and war becomes a defining metaphor for male agency. When this kind of aggression is valued, its opposite is devalued. When “male” aggression is valued, “female” lack of aggression is devalued, meaning that women themselves, associated with this “womanly” trait, come to be identified as a negative. Being a good man has come to mean being not like a woman. in this way, war contributes significantly to the hatred of women, and reciprocally, contempt for women contributes to the reproduction of war. (Borderline, p. 1)

I would ask my fellow Christians, as well as my socialist sister and brothers, to bear this in mind as the election season progresses, especially if Senator Sanders secures the nomination, because if a self-proclaimed socialist stands in opposition to a Republican (a party whose main organizing principle is demonstrably white supremacy, and whose leading candidate now is a dangerously fascist-like nativist), the red-baiting will begin in earnest.

Sanders might be critiqued for a number of things by both Christians and socialists. Many Christians will not agree with his stand on abortion. Many pacifist Christians and socialists will not agree with his support for the so-called war on terrorism, or even his support for the State of Israel. And yet, many of us will agree with his stated intent to mobilize movements in support of single-payer health care, a livable minimum wage, tuition-free college, and public works jobs. In any case, both Christians and socialists are obliged, in my opinion, to dig deeper into these issues than convenient truisms, shortcut accounts of history, and guilt by association fallacies.

And we might use this period to spend more time getting to know each other, because if Sanders wind, the watershed is that the stigma will have been removed from socialism, and we may want to figure out what that means together.

I very much look forward to reading this essay later. I always find your writing trenchant and thought-provoking.

ReplyDeleteHave you seen the new piece by Michelle Alexander, author of The New Jim Crow: Mass Incarceration in the Age of Colorblindness, on Clinton and race? She doesn't endorse Sanders, per se, but she's recently said she endorses the "political revolution" he is calling for, and says that Black voters should reject the Clintons, who are trying to "play" them again.

http://www.thenation.com/article/hillary-clinton-does-not-deserve-black-peoples-votes/

Ta-Nahesi Coates, who has criticized Sanders for rejecting reparations, also said he would vote for Sanders this morning. Harry Belafonte also just endorsed Sanders.

I need to read more of your work. It's hard to trust most authors because of their hidden agendas & lack of sacrifice. But your aim seems to be about examining our history & most importantly dissecting "the truth". The discourse you've laid out is the kind we need to put on the table and ruminate on. Our future as a bastion of hope for the voice of civil liberties may be in jeopardy if we follow our present course.

ReplyDeleteThis is a really fascinating essay. Thanks.

ReplyDeleteThis comment has been removed by a blog administrator.

ReplyDeleteThis comment has been removed by a blog administrator.

ReplyDelete