In Part 11, we was how sugar was one commodity that took off on the wings of respectability. Sometimes, studying one particular commodity is a way of gaining a fuller perspective on capitalism in all its complexity. In this installment, we will look at sugar.

The first sweetened cup of hot tea to be drunk by an English worker was a significant historical event, because it prefigured the transformation of an entire society, a total remaking of its economic and social basis. We must struggle to understand fully the consequences of that and kindred events for upon them was erected an entirely different conception of the relationship between producers and consumers, of the meaning of work, of the definition of self, of the nature of things.

-Sydney Mintz, “Sweetness and Power”

In Grecia, Costa Rica, where once I resided, the mountains are checkered with vast coffee and sugarcane fields. The cane has long leaves like corn. It rattles in the wind, and the fields go dark then light again as clouds pass over.

I had my first taste of raw cane in Vietnam, when a local man offered me a stick to pacify my imperial hatred. I still love cane, like a child, the crisp biting off, the chewing out of the melony sweetness, and spitting the bagasse. I still carry the guilt that man’s kindness stamped on me.

Nicaraguans work the cane fields here in Costa Rica. 90 percent of the laborers are Nicaraguans. Nicaragua is Costa Rica’s poor neighbor, and like the US – where our poor neighbors from Mexico and Central America are employed to lower the wage floor – Nicaraguans are the grunt workers. Like the Hispano-Latinas that work in the US, the Nicaraguans here – some working only for food – are reviled by their hosts.

It’s the one ugly aspect of Costa Rican society that contaminates a people otherwise cordial and peaceable in my experience, this national emity against los Chochos.

People seem compelled to strip away the personhood of a lower caste, much as I stripped away the personhood of Vietnamese, because I was obliged by circumstance to control them. It inoculates us from responsibility. We are no longer our bothers’, or sisters’, keepers.

The brutal strenuousness of cane work was the reason it was associated early on with slavery. In the absence of debt and dependency, no subsistence farmer would work for a wage in the cane fields. Workers had to be separated from their land, by debt, expropriation, or kidnapping. Ivan Illich once noted, “Modern development has been, at bottom, a war on subsistence.”

Sugarcane was first cultivated for crystalline sugar in India, around 350 AD to please the palates of the dominant caste. By the 7th Century, Arabs were cultivating it as a commodity on plantations; and this is when slavery became economically associated with the production of crystalline sugar, later called by European purchasers “the sweet salt.”

Nonetheless, it was a niche commodity. There was neither the capacity nor the demand for the expansion of a “sugar industry” until the 15th Century, when a sugarcane roller-mill was designed in the Mediterranean. Cane has a tough outer skin, puncutated with hard knots, and the spongy bagasse re-absorbed the sugar juice as it exited the older presses. The new design doubled the output; and the search for the new design contributed significantly to the industrial revolution.

Like the cotton gin in North America, this one machine had profound consequences for relations of production and land in the Americas, because the press made more and larger plantations profitable.

With the European migration to the Americas, beginning with Columbus later in the same century, sugar became the prime mover in the African slave trade. The ideal climate for sugar production is subtropical and tropical; and the so-called New World – largley uncultivated – provided vast expanses of fertile land for sugar plantations. Indigenous populations living on those lands rather quickly fell before European diseases against which they had little natural immunity, and before the guns of British, French, Spanish, and Portuguese militias. Without the indigenous as slaves, sugar production defaulted to the use of African slaves as the lowest-cost available labor.

In C. L. R. James’ lively account of the Haitian Revolution, The Black Jacobins, he describes the incredible, and often gratutious, cruelty of French slaveowners in Saint Domingue (now Haiti), then the most productive and profitable colony in the hemisphere. It was more profitable in some cases to work slaves to death than to sustain them.

When profit dehumanizes a population to this degree, then profit-makers have to prove that dehumanization with sadism, again and again, to justify themselves. As punishment for minor infractions, and sometimes as drunken sport, slaves were subjected to incredible cruelty.

The whip was not always an ordinary cane or woven cord…sometimes it was replaced by a thick thong of cow hide, or by the lianes, a local growth of reeds, supple and pliant like whale bone…The slaves received the whip with more certainty and regularity than they received their food. It was the incentive to work and the guardian for discipline. But there was no ingenuity that fear of a depraved imagination could devise which was not employed to break their spirits and satisfy the lusts and resentment of their owners and guardians.

Irons on the hands and feet, blocks of weed that the slaves had to drag behind them wherever they went, the tin-plate mask designed to prevent the slaves eating sugar cane, the iron collar. Whipping was interrupted in order to pass a piece of hot wood on the buttocks of the victims; salt, pepper, citron, cinders, aloes, and hot ashes were poured on the bleeding wounds. Mutilations were common, limbs, ears, and sometimes the private parts, to deprive them of the pleasure which they could indulge in without expense. Their masters poured burning wax on their arms and hands and shoulders, emptied the boiling sugar over their heads, burned them alive, roasted them on slow fires, filled them with gun power and blew them up with a match (this was called 'to burn a little powder in the ass of a nigger'); buried them up to their necks and smeared their heads with sugar that the flies might devour them, fastened them near to nests of ants or wasps; made then eat their excrement, drink their urine and lick the saliva of other slaves.

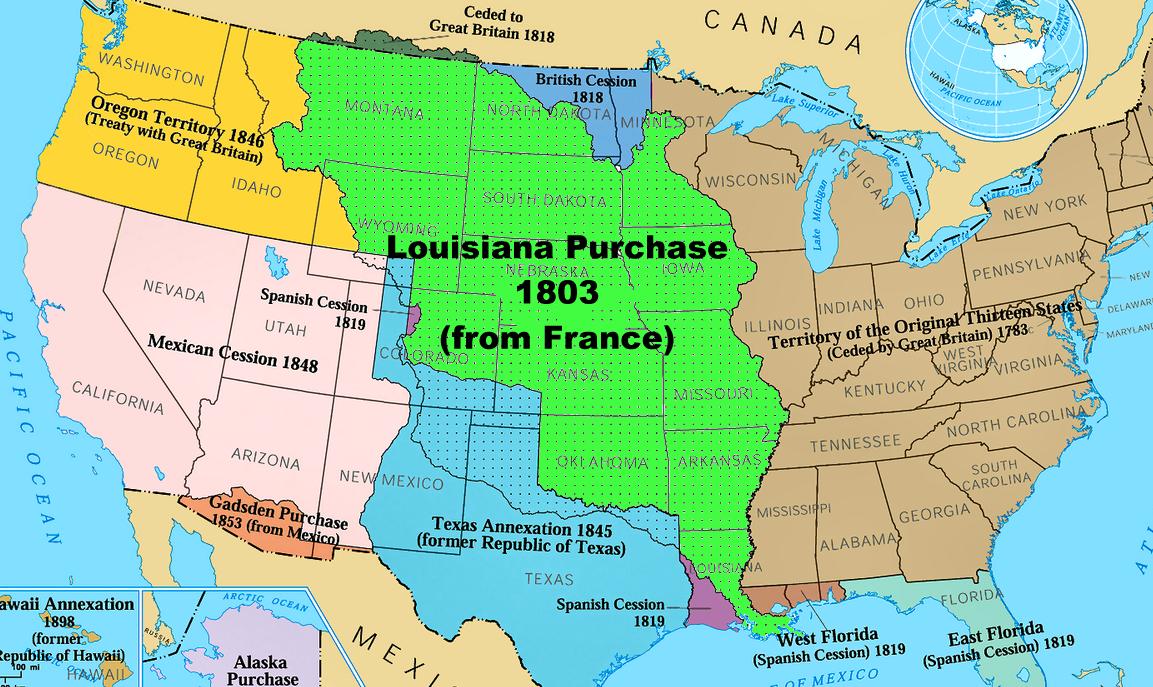

The visciousness and greed of the French colonials engendered its own consequences. When slave-Generals Touissant L’Overture, Jean Jacques Dessalines, and Henri Cristophe led the rebellious slaves in an insurrection against the French overlords, Napolean Bonaparte’s treasury was depleted by the counter-insurgency effort. He needed money, and fast, to fight the British, leading him to negotiate the Louisiana Purchase with President Jefferson – himself a slaveowner – in the newly-minted United States. All or part of 14 eventual states were acquired through that purchase, netting Napolean 60 million francs in cash and 18 million francs in debt forgiveness for the United States. The then-residents of the “purchase,” of course, were not consulted on the sale.

When sugar was first imported to Europe, it was a luxury item. Taking their cue from Asians, it was seen first as a medicinal agent. Given sugar’s demonstrated effects on serotonin levels, it is not surprising that these effects were incorporated into the body of health and healing lore.

Constant consumption of sugar, like our constant consumption of sugar, masks those effects – effects that are further masked by the smorgasbord of chemicals that modern metropolitans consume in our obsessive and alienated monitoring of how we happen to physically feel at any given moment.

If there is a canonical work on the historical anthropology of sugar, it is Sidney Mintz’s Sweetness and Power: The Place of Sugar in Modern History (Penguin, 1986). This tome is available as a free downloaded e-book.

Mintz details a host of interesting, and often bizarre medicinal uses for sugar in the past. He quotes Tobias Venner, 1620, writing to compare the medicinal value of honey with that of sugar:

Sugar is temperately hot and moist, of a detersive facultie, and good for the obstructions of the breast and lungs; but it is not so strong in operation against phlegm as honey… Sugar agreeth with all ages and complexions; but contrariwise, Honie annoyeth many, especially those that are choleric, or full of wind in their bodies… Water and pure sugar onely brewed together, is very good for hot, cholericke, and dry bodies, that are affected with phlegm in their breast…

In the same year, a medical man named James Hart questioned sugar’s medicinal efficacy in Klinicke and the Diet of Diseases. This controversy lasted for more than a century. In Dr. Frederick Slare wrote an apologetic tract on behalf of medicinal sugar entitled A Vindication of Sugar Against the Charges of Dr. Willis, Other Physicians, and Common Prejudice: Dedicated to the Ladies. Slare touted sugar as a veritable cure-all, its one drawback being that it, in his opinion, made women too fat when taken in excess.

Sugar was becoming cheaper and more available to lower classes, and so was being promoted by the sugar industry that endeavored to produce greater demand through such propaganda. But the real explosion of the sugar market, especially in England, was opened up by the simultaneous trends of enclosure and industrialization.

In the late medieval period, a new international commodity came on the scene in England: wool. This ignited an antagonism between the interests of subsistence farmers and sheep owners that lasted from the 13th Century to the 19th Century, whereupon the English government decisively came down on the side of the wool industry.

The outcome of this antagonism – lost by the subsistence farmers – was called “enclosure.” In brief, small arable plots of land were consolidated and then "enclosed," that is, deeded to one owner and fenced off. Each step forward by the enclosure movement created larger and larger numbers of landless peasants, who were seen as potential threats to social stability (ergo, occasional opposition to enclosure from the aristocracy), and who were forced in many cases to go to the emerging cities to seek their survival. Enclosure, then, went hand in hand with the evolution of urbanization.

Urbanization itself created the conditions necessary for industrialization by creating a vast army of desperately unemployed poor living in squalid conditions in the cities. These conditions were the background for Charles Dickens’ novels, and came to be know as “Dickensian conditions” by future scribblers.

As production of sugar increased during that same general industrializing process, it became cheap enough to be available to this new class of industrial workers, along with a cheap source of caffeine – tea – from the English colony in India. For these industrial laborers, heavily sugared tea became an energy substitute for more nutritious and expensive fare. Mintz called sugar and tea “proletarian hunger killers.”

As we saw in the last installment, sugar also became a status product associated with the invention of "respectability."

For the first time in history, a large metropolitan population became accustomed to consuming sugar – more sugar than any population had every used – and more than the human organism had ever evolved to metabolize.

This process of the sugar-ization of the human diet – especially in the industrial metropoles – has grown until the present. Today, in the United States, the average person consumes 31 five-pound bags of sugar a year. This doesn’t count the recent addition of vast quantitites of cheap high fructose corn syrup to the US diet. In 1700, the average person consumed around 4 pounds of sugar a year. That means we are approaching an eight-fold increase.

What happens to us when we eat this white stuff? We can start with the senstation.

Taste receptor T1R3 gives us our ability to experience sweetness. Its evolutionary advantge – reinforced by the pleasurability of sweetness – is that it allowed our ancestors to identify the difference between edible and poisonous (bitter) materials for nourishment. Obviously, refined sugar did not exist half a million years ago, so evolution had no part in what we today refer to as sugar craving, aside from this T1R3 receptor’s ability to discern the presence of natural sugars (a high-energy input). One can’t crave a food that does not yet exist.

The pleasurability of sweetness, however, can lead us – like any highly sensible organism – to seek it out for the pleasurable sensation alone. Pleasure is biologically traceable to the release of chemicals into our brains, in this case seratonin, a powerful neurotransmitter that we experience as a “high” of well-being.

A large bolus of sugar can stimulate a corresponding bolus of seratonin. Stimulation is not problematic when the endocrine system – a complex set of feedback loops – is stable (homeostatic). But the human metabolic system did not emerge in response to large quantities of crystal sugar, a substance that takes what would naturally be a gentle progression of shallow metabolic waves and converts them into roller coaster highs and lows.

The seratonin-sugar connection is mediated by insulin production – the hormone that facilitates glucose (simple sugar) metabolism in the body. Large quantities of sugar are recognized by the endocrine system as large amounts of more complex nutrients, creating an insulin production overshoot, metabolizing the sugar with insulin to spare.

Insulin without sugar is dangerous, and – as some diabetics know – can lead to an emergency called “insulin shock.” Glucose is a more immediate necessity to the brain than oxygen, and an oversupply of circulating insulin can deplete glucose to dangerously low levels. Most of us have experienced this condition momentarily – hypoglycemia – when we perhaps consumed a sweetened coffe or fruit juice for breakfast, without other food, then found ourselves suddenly becoming weak-kneed and shaky a couple of hours later.

Refined sugar, then, increases the frequency of our experience of hunger, as well as stimulating a radically oscillating seratonin cycle that is experienced as feeling low without it and feeling high with it.

Whether this makes sugar “addictive” is controversial; but only because the definition of “addiction” is itself the bone of contention. It certainly associates sugar with the statistical trend toward obesity in many societies, though, which corresponds to an epidemic of diabetes.

This was not understood by scientists until the 20th Century, so these effects were not associated with sugar in a causal way, or in their consequences, when sugar first became a European commodity. The effects occurred nonetheless. Sugar came with a built-in dependency, as well as its psychological attraction - the pleasurable sensations deployed in the face of distress, or the modern phenomenon of "comfort food" in the midst of our epoch's consumer driven-ness and alienation.

This reinforcement at the most visceral level has made sugar a formdable commodity even in the face of greater public understanding about the health effects of excessive and frequent sugar consumption.

In 2006, the International Diabetes Federation wrote:

Diabetes, mostly type 2 diabetes, now affects 5.9% of the world’s adult population with almost 80% of the total in developing countries. The regions with the highest rates are the Eastern Mediterranean and Middle East, where 9.2 % of the adult population are affected, and North America (8.4%). The highest numbers, however, are found in the Western Pacific, where some 67 million people have diabetes, followed by Europe with 53 million.

India leads the global top ten in terms of the highest number of people with diabetes with a current figure of 40.9 million, followed by China with 39.8 million. Behind them come USA; Russia; Germany; Japan; Pakistan; Brazil; Mexico and Egypt. Developing countries account for seven of the world’s top.

One cannot lay the diabetes epidemic solely at sugar’s door. Obviously, lifestyle and genetics contribute to diabetes’ morbidity; but the introduction of increasing quantities of this substance is just as obviously involved.

One sure predictor of higher morbidity is poverty, especially poverty inside the developed metropoli. Low-cost calories, just as they were for the factory workers of Dickens’ age, are almost a staple for the poverty-diet.

The microvascular and macrovascular effects of diabetes also exacerbate the condition of cardiovascular patients. Juvenile diabetes, especially Type 2 – once rare in juveniles – is now a major public health concern in the United States. It will remain a concern for a long time.

One of the main concerns with type 2 juvenile diabetes is the affects it can have later on in a child's life. Children with type 2 diabetes have been found to have more life threatening complications than type 1 diabetics. Some of the major problems juveniles with this type of diabetes face include heart disease, damage to the nervous system, renal failure, blindness, and limb amputations, particularly of the feet and lower legs.

-Andrew Bicknell

Now the issues with sugar have been compounded by the production of corn sugar: High fructose corn syrup (HFCS). HFCS was put on the US table by a combination of import tarrifs on foreign sugar (to insulate the US sugar industry from foreign competition) and extremely generous government subsidies to the domestic corn industry.

A highly recommended documentary film about this industry is entitled King Corn, linked here for free viewing.

HFCS and table sugar are very close in terms of their relative fructose content ( a health concern because fructose is metabolized in the liver, putting stress on that organ, and rapidly converts fructose into body fat. Recent reports of widespread mercury contamination in HFCS, as well as increasing dissatisfaction with a corn industry that has accumulated immense political power, have sullied the reputation of HFCS, and sent many – partially informed – to see cane or beet sucrose as “the good sugar.”)

The clash between the sugar industry and the corn industry is a clash of the political titans. Both have been the recipients of billions of dollars of the taxpayers’ largesse; and both industries routinely rent their own elected officials.

LAST YEAR the Bush administration negotiated a free-trade agreement with the five Central American nations and the Dominican Republic. It has yet to submit the deal to Congress because trade politics has grown so poisonous. Even though the Central America deal, known by its acronym, CAFTA, would help a struggling region on the doorstep of the United States, and even though it would modestly boost U.S. prosperity, a coalition of special interests has seized Congress by the throat. The most aggressive and least deserving of these is the sugar lobby.

U.S. sugar policy stands for all that's bad about our political system. The government restricts imports through a series of quotas, pushing U.S. sugar prices to between two and three times the global market rate. As a result, a handful of sugar producers, notably in Florida, a battleground electoral state, pocket $1 billion a year in excess profits. To protect this cozy arrangement, the sugar barons plow a chunk of their revenue back into the political system. During the 2004 election cycle, two Florida sugar companies gave a total of $925,000 to election coffers.

-“Big Sugar,” Washington Post Editorial, April 16, 2005

So consumers get to pay the sugar industry directly, through subsidies, and again indirectly through doubled, or tripled, sugar prices. This is just a peek at the story of big sugar, which I’ll leave as it is, because the story of big sugar is easy to find, and it’s only a premise here to another point.

The corn lobby, unlike the sugar lobby, doesn’t stand freely, but exists as a subset of the Midwest agribusiness lobby centered around three transnational corporations that dominate the sector: Archer-Daniels-Midland, Cargill, and Monsanto.

The transformation of corn alongside the transformation of the general economy has been driven by these leviathans’ quest for profit and domination of the food market. Right now, they are green-washing ethanol to perpetuate taxpayer subsidies for that land-wrecking boondoggle. But we are looking specifically at the production of corn sugar, or HFCS.

The competition between sugar producers and corn syrup producers has muddied the water on the health and nutrition debates about sweeteners, because any negative points produced independently against either product is now grist for their competition.

Not our topic here, but a good one. Here we'll continue down the sugar path.

The sugar program is essentially a producer cartel run out of Washington. The Agriculture Department operates a complex loan program to guarantee sugar growers certain prices, which it enforces with import barriers and domestic production controls.Almost $2 billion annually is culled from the pockets of taxpayers in the United States to directly subsidize the sugar industry. US consumers pay around $90 miilion in addition to that based on the higher cost of ingredient-sugar in other products. While this example of "corporate welfare" is a hot-button for a lot of people across various political sprectra, the real assist the sugar cartel gets from Washington is an import duty to prop up the already inflated cost of sugar.

-Chris Edwards

Subsidies that began as rescue funds and backstops for family farms in the New Deal era have been finagled by corporate lawyers and predatory capitalists into a special public-private partnership of the super-rich. The poor live in conditions determined by the law. The rich change the laws by buying new conditions.

In the CBC's documentary, Big Sugar, Halloween is called an annual "$4 billion sugar festival." Author Adam Hookshield calls sugar "the oil of the 18th Century," because of how sugar generated fortunes and war at the same time.

In the United States today, residents pay three times as much for sugar as the rest of the world. Most of that revenue goes to three giant sugar companies that are encamped along the Everglades in Florida.

Cartel: from Wikipedia:

A cartel is a formal (explicit) agreement among competing firms. It is a formal organization of producers and manufacturers that agree to fix prices, marketing, and production. Cartels usually occur in an oligopolistic industry, where there is a small number of sellers and usually involve homogeneous products. Cartel members may agree on such matters as price fixing, total industry output, market shares, allocation of customers, allocation of territories, bid rigging, establishment of common sales agencies, and the division of profits or combination of these. The aim of such collusion (also called the cartel agreement) is to increase individual members' profits by reducing competition.Above, we referred to rice subsidies in the US creating hunger in Haiti.

One can distinguish private cartels from public cartels. In the public cartel a government is involved to enforce the cartel agreement, and the government's sovereignty shields such cartels from legal actions. Contrariwise, private cartels are subject to legal liability under the antitrust laws now found in nearly every nation of the world.

Competition laws often forbid private cartels. Identifying and breaking up cartels is an important part of the competition policy in most countries, although proving the existence of a cartel is rarely easy, as firms are usually not so careless as to put agreements to collude on paper.

Until the 1980s, Haiti grew almost all the rice that it ate. But in 1986, under pressure from foreign governments including the United States, Haiti removed its tariff on imported rice. By 2007, 75 percent of the rice eaten in Haiti came from the United States, according to Robert Maguire, a professor at Trinity Washington University. Haitians took to calling the product "Miami Rice."The untold story is that Haiti's second biggest export, after coffee, is sugar. This is, in the current economic paradigm, how sugar subsidies undermine access to dollars in indebted nations.

The switch to importing rice was driven by U.S. subsidies for its own growers, said Fritz Gutwein, Co-Director of the social justice organization Quixote Center and coordinator of its Haiti Reborn project. The result in Haiti was a neglect of domestic agriculture that left many of the country's farmers, still the majority of its population, unable to support themselves, fueling waves of urban migration and environmental degradation.

America needs to look at how its own agricultural polices affect Haiti," Gutwein said.

FULL article

No one here is defending sugar production itself, however - an environmentally destructive and labor-exploitative process, and one that will only increase now that Brazil is paving the way for the worst idea lately, growing sugar to make alcohol fuel.

As we approach sunset on the day of hycrocarbon Homo sapien, a day where we mined the unliving substrates of the planet to fire industry and grow a billions-strong population that depends on a system of energy-slaves, we are now faced with the threat that to sustain the energy-slave regime, we will mine the topsoil of the planet.

Franklin Roosevelt, who I am not prone to quote, once said, "The nation that destroys its soil destroys itself." We could just as easily say, the world that destroys its soil destroys itself.

Alice Friedemann says, "Ethanol is an agribusiness get-rich-quick scheme that will bankrupt our topsoil." I'll link her article on biofuels and peak soil, in case anyone is inclined to read about this white elephant.

Right now, 121 countries produce sugar. In studying the environmental impact, we cannot limit ourselves to food sugar, because the biofuel folly is growing now.

Sugarcane is guilty of all the sins of industrial monocropping. It sterilizes soil and causes its erosion. It salinizes soil through irrigation, which also depletes aquifers. It uses massive petroleum and chemical inputs that have the adverse effects we already know. It disrupts biodiversity. What exacerbates the problem with cane is that it is grown in climates where a great deal of the earth's biodiversity currently exists; so its impact is considered the worst of any crop in its destruction of biodiversity.

The Everglades and the Great Barrier Reef are both damaged and threatened by sugarcane. In New Guinea, sugar regions have already lost 40% of their soil fertility in 30 years.

The working conditions for cane laborers are uniformly dreadful around the world. The Brazilian ethanol producer, COSAN, is facing a suit right now for using slave labor.

The deeper issue is that the land growing sugar is land in countries where land redistribution for subsistence will be the key to long term survival.

Unfortunately, sugar creates its own demand in its physio-psycholgy; and the demand for sugar is rising around the world.

.jpg)

No comments:

Post a Comment