This installment is cribbed substantially from a lecture I gave at Penn State in 2012. If it looks familiar to a few, that is why. While it doesn't make much mention of Christianity, by now readers should be habituated to trying to see this series on the history, mechanics, and psychology of capitalism with one eye on the Gospels. -SG

In the early 80s, macro-economic forces were shaping a new form of international economy and corresponding changes in US foreign policy. The story could begin as far back as World War I, but for the sake of brevity, we will begin the story during just a few years prior, in 1973.

In 1973, as a protest against the US rescue

of Israel from an impending defeat by the Egyptians in the Yom Kippur

War, Arab nations implemented an oil embargo against the US, creating

day-long gas lines that broke up only when filling stations pumped out

their last drop of gasoline.

Oil prices rose dramatically, creating a

tremendous windfall profit for oil producing states. Oil was

denominated in US dollars, and those additional dollars were invested at

Wall Street by the same oil producers who were withholding gasoline

from the US.

Wall Street does not sit on money. Wall

Street firms are rentier capitalists, that is, they use money to make

more money through royalties (like interest); and so the glut of petrodollars from the Arab oil states was

converted by Wall Street into vast development loans for poorer countries through the International Monetary Fund, especially

in Latin America.

These loans, not unlike the subprime

mortgages we know and love today, had adjustable rates. During the

latter Carter years, the United States – for reasons we won’t elaborate

here – suffered something the economists hadn’t anticipated:

simultaneous lack of growth – stagnation – and rapid inflation, which

came to be known as stagflation.

Federal Reserve Chair Paul Volcker

responded to this with something called the Volcker Shock, that is,

since inflation was the greater danger to the rentier capitalists, he

raised the interest rate from 7.5% to 21.5%, doubling US unemployment

rates, while making large creditors whole.

These elevated interest

rates were passed along, via Wall Street institutions, to those Latin

American countries that had received the aforementioned development

loans, creating a crisis in Latin America.

This shock doctrine lasted

from 1979 to 1982, and when Reagan was in office in 1982, Mexico

announced that it was about to default on its Wall Street loans,

stranding Wall Street with more than $100 billion in losses.

Not for the first time, and certainly not

for the last, the US government stepped in to bail out Wall Street’s

finance capitalists. This was a bailout loan to Mexico, but the intent

and the urgency was to ensure that Wall Street didn’t take a bath on the

Mexican default. The vehicle for loans to cover the previous loans to

Mexico was the International Monetary Fund, an international institution

formed in the latter years of World War II, in which the US exercises a

very dominant role. But this time, the bailout loans had something

attached to them in addition to interest, called “conditionalities.”

These conditions included several

ultimatums – that Mexico’s internal markets be opened to US-based

investors, including US multinational corporations, that labor and

environmental standards be rolled back to increase the rate of profit in

order to pay back the restructured loans, and that regressive tax

structures be implemented – also to assist in the payback of the loans.

A structural imperative, though not one of the specified conditions,

was also that Mexican enterprises – in particular agriculture – be

converted from production for local consumption to export products to

get more of the US dollars required to service the restructured but now

vastly expanded external debt.

Using similar crises, the IMF proceeded

over the next few years to impose these conditionalities – called

structural adjustment programs – on the majority of nations of the

global periphery, effectively undermining their national sovereignty

inasmuch as the IMF, the World Bank, and the World Trade Organization,

all US-dominated pre-market institutions (remember the earlier discussion of Polanyi's theses on pre-market institutions) that manage the so-called

“free” market, came to dictate the economic policies of these

structurally-adjusted nations.

While these were originally contingent

measures used to take advantage of Mexico’s crisis, the Reagan

administration soon realized that they had stumbled onto a model that could be used around the world to open home markets to US

investment under conditions that were very advantageous to US

investors. Moreover, it was a way to capture the political

leadership of debtor nations in a dollar-dominated system, which

would come to be known as neoliberalism.

I realize that this is a fly-over at

several thousand feet, and that I am overlooking many of the details of

this process, but I only want to establish a kind of historical context

wherein neoliberalism is intelligible, in order to explain subsequent

claims about US foreign policy, which has been largely formed by the

imperatives of neoliberal policy.

Neoliberalism itself is now in a bit of a

crisis, because the same financial establishment that was turned loose

on the world by the emergence of neoliberalism has both worn out its

welcome around the world – creating great popular resistance to its

diktat – but it has created tens of trillions of dollars of fictional

value from runaway speculation, threatening the very currency around

which the entire system is based.

The US-dominated financial system, called

the “Dollar-Wall Street regime” by Peter Gowan and Susan Strange, also

found a way to exercise managerial control over first world economies

like Western Europe and emerging market economies like China and

Brazil. This power was exercised not in the US role as creditor, but in

the US role as debtor.

This story actually begins at the end of

World War II and continues to the present. The Soviet Union – itself

savagely wounded by the war – attempted to secure a post-war partnership

with its capitalist war allies in order to regroup. More than 27

million Soviet citizens had been killed, and cities were in ruins all

the way to Stalingrad. When the Truman administration opted for the

National Security State as an industrial strategy that could capitalize

on the ramp-up for the war, it needed an enemy to justify the

expenditures of what Eisenhower would christen the “military-industrial

complex.” The overtures from the USSR for a post-war peace were rejected

in favor of official hostility by Truman. This provocative posture

locked Western Europe into a military alliance with the US, and put an

official stamp on the US foreign policy of “containment.”

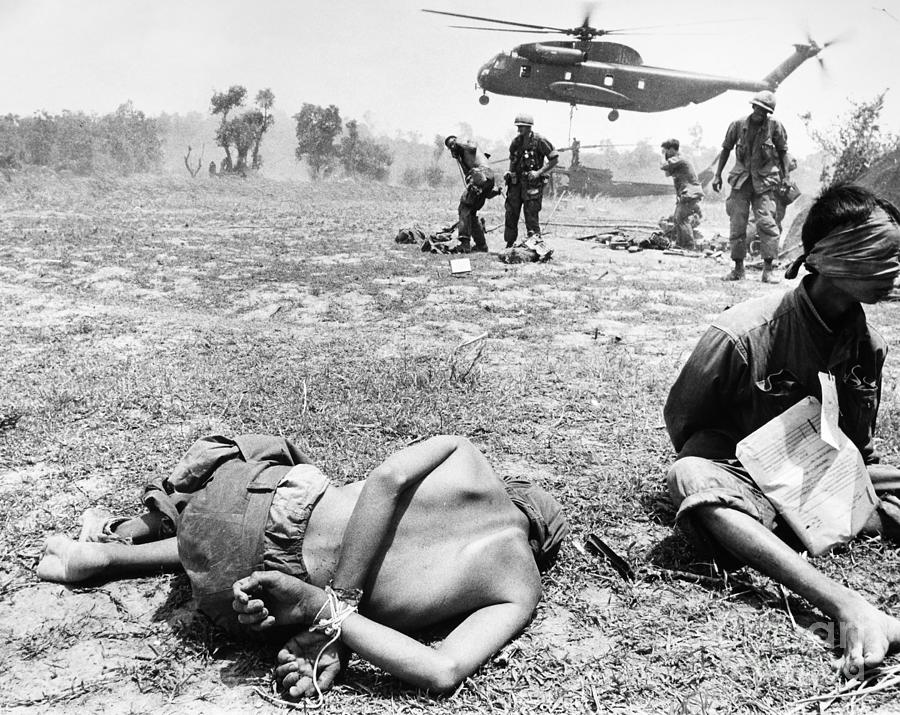

This inaugurated a long period of proxy

war, the first in Korea, later in Vietnam. While the US was enjoying

the fruit of post-war dollar dominance, Keynesian high employment, and a

robust trade surplus, however, the militarization of US domestic and

foreign policy created a mounting national debt. The US was indebting

itself to other metropolitan nations. The US was borrowing money from

Europeans to finance its military adventures in Asia, then running

printing presses to make up the difference. Because the dollar’s value

was fixed for redemption at 1/35th of an ounce of

gold, the US could print money without fear of draining the dollar of

its value, which was being used for capital investment in Europe.

In the theoretical market, the value of a

currency is determined by how it balances against an aggregate of

commodities. Too few units of currency and prices fall. Too many units

of currency and prices rise. The latter is inflation – the nemesis of

loan sharks and bankers because it reduces the future purchasing power

of collected principle and interest. So the dollar was losing

purchasing power on the market, even as it remained exchangeable for

European currencies at the same fixed rate.

The US was printing more money, but because

the dollar was fixed to gold, the Europeans were watching their markets

flooded with overvalued dollars, which they had to accept. The market

may have been saying that a dollar should be redeemable for francs or

marks or pounds at one rate, but the post-war currency-control regime

determined that Europeans had to continue to give away purchasing power

with every currency exchange for devalued dollars. The US was exporting

its inflation to Europe by repaying its military expansion debts to

Europeans in under-valued dollars.

So when the first Special Forces advisers

went to Vietnam in 1957, the system that appeared so robust on the

surface was already creating the conditions for its next crisis.

The Europeans, later buying gold elsewhere

at well above the $35 per troy ounce, held onto their dollar denominated

assets, hoping to redeem their dollars at something approaching their

initial investment later. But by 1967, with the Vietnam War driving the

US deficit to record levels, France started cashing dollars out for US

gold, draining the US gold stock. The Keynesian system of tightly

controlling finance capitalists, which included fixed currency exchange

rates pegged to a gold-backed dollar, began to collapse in the face of

the US decision to militarize its domestic and foreign policy.

On March 31, 1968, millions of Americans

heard Lyndon Johnson announce on television that he would not run again

for the presidency, and that he would not substantially escalate the

Vietnam War, despite the strategic setback of the Tet offensive nearly

two months earlier.

Unperceived by the public at large, the

point finally had been reached at which depletion of the U.S. gold

holdings had abruptly altered the country’s military policy. As

financial historian Michael Hudson noted:

“The European financiers were forcing peace on us. For the first time in American history, our European creditors had forced the resignation of an American president.”

But when the 1968 elections arrived, we saw

a scenario that is familiar to us again. Democrats could not publicly

argue for an end to the war, because withdrawal would mark the

destruction of the myth of US military invincibility. The options

available in response to the collapse of the US Gold Pool were (1)

withdrawal from Vietnam, (2) continue the war and accept further losses

of gold and with it the erosion of US global power, or (3) force the

abandonment of the entire Bretton Woods regime beginning with the gold

standard. Because the Democrats alienated a huge fraction of their

base by refusing to oppose the war, Republican Richard Nixon was

elected. In 1971, he selected Option 3. He abandoned the gold standard

for the US dollar.

This was a staggering checkmate against the

US’s alleged global allies. They had to do something with their

trainloads of dollars to prevent their uncontrolled devaluation.

Quoting Hudson,

“By going off the gold standard at the precise moment that it did, the United States obliged the world’s central banks to finance the U.S. balance-of-payments deficit by using their surplus dollars to buy US Treasury bonds, whose volume quickly exceeded America’s ability or intention to pay.

“Twenty-five years [after WWII], the United States [discovered] the inherent advantage of being a world debtor. Foreign holders of any nation’s promissory notes are obliged to become a market for its exports as the means of obtaining satisfaction of their debts.”

As the old saying goes, “if you owe the

bank a thousand dollars, you have a problem. If you owe the bank a

billion dollars, the bank has a problem.”

Nixon had not only erased US debt held by

allies and forced perpetual European support for US military

expenditures with the threat of tearing everyone’s financial house down,

he had opened the way for rentier capitalists to escape the limitations

put on it during the New Deal. That is precisely why Peter Gowan

referred to Nixon’s risky destruction of the Bretton Woods fixed

currency exchange rates as the “global gamble.”

New system: debtor imperialism.

Susan Strange referred to the new system as

“casino capitalism.” The rentier capitalists were free to speculate

without constraints; but more importantly, the US government, in

collusion with Wall Street, had a new weapon to use against recalcitrant

nations. Domestic currencies could be speculatively attacked; which is

exactly what the US did to several Asian countries in 1998, which

unexpectedly almost crashed the world economy. The threat of attack on

currencies obliged central banks abroad to hold US dollars – in the

form of US Treasury Bonds – in reserve, as a defense against speculative

attacks on their currencies. These nations then became US creditors;

but they were the banks who – as in the banker’s joke – had the problem.

To this day, no one – including China,

about which there is a great deal of financial fear-mongering – can

afford to begin a run on the dollar. Too many nations hold too many

dollars to sell the dollar down without cutting off their noses to spite

their faces. And yet all these creditor nations know that the US has

neither the capacity nor the intention of paying back those loans.

China holds over a trillion dollars in US

Treasury Bonds. Japan holds almost a trillion. The United Kingdom

holds over 400 billion. Brazil holds more than 200 billion. The list

goes on. If China were to initiate – as some China-phobes suggest – a

cash-out of its t-bills, and that cash-out caused a run on the dollar

destroying half its value, China would lose more than half a trillion

dollars in purchasing power. This is a game of chicken that the US has, so far, won every time.

The key to dominance in the world of the late 20th and early 21st

Centuries has been dependency… interdependency, but of a very unequal

nature. We see this in really bad, really patriarchal marriages. A

husband depends on his wife for the management of the household, for a

lot of unpaid labor, and for the care of children, and the wife depends

on the husband for economic security; but in the event of a divorce, we

find that the wife comes out much worse than the husband, giving the

husband a threat to hold over the head of the wife. They depend on one

another, but that interdependence is not synonymous with equal status or

parity of power.

This is how US foreign policy is

constructed for the most part, as interdependencies in which the US is

the dominant partner. And there are few things that human beings depend

on more urgently than food; which brings me to a subject that is

imbricated with finance, but not the same as finance.

Money is not theoretically necessary for

life. Human life sustained itself before general purpose money. Human

life cannot be sustained, however, without its material basis in food.

If I might, I’d like to actually go deeper

on the topic of food than we generally do, into the realms of chemistry

and biology, for just a moment. I want to say a few things about energy

and nitrogen.

If you touch your friend or neighbor, appropriately, of course, you will find that he or she is a heater.

You are all warm. That heat is thermal energy that is part of the

overall energy system that constitutes your existence as an organism, as

a mammal, as a primate, and as an omnivore. You eat plants and animals

that have energy stored in them. The plant energy that animals eat

comes from the sun, whose energy is stored in the plants by

photosynthesis.

One of the chemical components of our world

that is necessary for most plant growth, therefore necessary for food,

and therefore necessary for our survival, is nitrogen.

Oddly enough, after Timothy McVeigh blew up

a federal office building in Oklahoma City, everyone – even

non-farmers – came to know that fertilizer is made with nitrogen.

Yet nitrogen is the most abundant element

in the atmosphere, so why should anyone have to “produce” it as a

fertilizer? We live our entire lives literally swimming in the stuff.

As it turns out, atmospheric nitrogen, like

atmospheric oxygen, is a Siamese twin. It consists of two, fused

molecules: N2, as it were. Plants have to break this down into single

molecules, then mix it with other stuff, in order to turn sunlight into

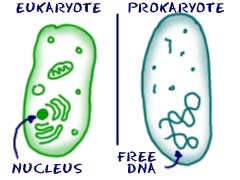

food. The process is called biological nitrogen fixation. Prior to human intervention, this fixation process was accomplished by prokaryotes (or non-nucleated bacteria) and diazotrophs (or ammonia-making bacteria.)

During World War I, the introduction of new technology, i.e. the

machinegun, and the adherence to pre-machinegun tactical doctrines, led

to huge armies being first mowed down like grass, then trapped facing

each other from pestilential trenches. One of the bright ideas for

taking advantage of this horror-film stalemate was the idea of killing

the enemy with poisonous gas.

During the war, Fritz Haber, a

German-Jewish chemist, was appointed director of the Berlin-based Kaiser

Wilhelm Institute for Physical Chemistry.

One of his jobs became the development of

chemical weapons. He would eventually invent a gaseous chemical called

Zyklon-B, a cyanide derivative, which would be used to wipe out millions

of his own co-religionists; but during WWI he was preoccupied with

chlorine and ammonia for the development of poisonous gases for the

battlefield.

His other preoccupation was nitrogen

fixation. He learned how to do that, synthetically, by combining

hydrogen and N2 under heat and pressure, along with an iron isotope and

aluminum oxide as catalysts. He had already patented this process

before the war; but it would take Carl Bosch, the eventual co-founder of

I. G. Farben (the company that marketed Zyklon-B) to

commercialize the process… which laid the basis for a population

explosion from 1.6 billion in 1900 to more than 7 billion today. What

he’d made was chemical fertilizer, and it meant that even land that was

unfit for agricultural cultivation could be rendered “productive.” The

food that feeds that additional 5 billion people is largely produced

with the assistance of chemical fertilizers and chemical poisons.

But “heat and pressure” are not some

infinite essence like space, nor are they immediately available like

atmospheric nitrogen. They are transient phenomena that must be created

through some procedure; in this case, using fossil hydrocarbons… lots of

them. Haber was looking at a crisis created by the depletion of guano –

bat and bird droppings used as fertilizer – mostly collected from the

islands off the coast of Chile; so he fell on a system that depended on

another exhaustible resource: fossil fuel.

After WWII, American farmers were using

prodigious quantities of chemical fertilizer across prodigious expanses

of arable land, along with a new chemical weapon itself, nerve gas… or

organophosphates, as insecticides, expanding their harvests far beyond

the American public’s capacity to consume.

The American manufacturing base had also

expanded during the war, and given that the US did not suffer the

devastation that Europe and Asia did during the war, the US emerged from

the war as a uniquely powerful actor. The other variable in the

expansion of food production was the thoroughgoing mechanization of

agriculture, another net consumer of fossil energy. The US began to

build farm machinery; and as part of its goal of maximizing profit for

farm machinery industries, as well as agricultural chemicals, it

began to promote something called “developmentalism” for the so-called

under-developed nations.

In 1943, the Rockefeller Foundation, Ford

Motor Company, and the Mexican government established a joint venture

called – in English – the International Center to Improve Corn and

Wheat. Standard Oil – a Rockefeller company – was manufacturing

fertilizer, and Ford was building tractors. This was the beginning of

the organized effort by first world corporations, with the active

support of the US government, to push agricultural commodities into

these so-called underdeveloped nations. By 1959, they had opened rural

development academies in Pakistan, and by 1963 in the Philippines. These academies were performing research and development on

high-yielding cultivars of wheat, corn, and rice. By the time of the

Nixon administration, 120 of the largest agribusiness multinationals had

established a joint program with the United Nations Food and

Agriculture Organization.

The transformation in agriculture that

followed was called the Green Revolution, a term coined in 1968 by US

Agency for International Development Director William Gaud.

If ever there were a revolution from above,

this was it. And it did accomplish a great deal. Caloric intake from

cereal grains worldwide increased 30 percent per capita by 1990, and the

prices of grains fell. The availability of more staple grains also

supported a doubling of world population between 1960 and 2000.

Yet these very general statistics don’t

tell the whole story. There were a number of qualitative changes that

accompanied these statistical quanta. One early condition of World Bank

development loans was that recipient nations industrialize their

agriculture.

Smallholders were pushed off land to make

way for large monoculture fields. Mechanization cut the number of

necessary field workers to a fraction, and a process began whereby

millions of formerly rural people – who were monetarily poor, but

capable of self-reliant subsistence agriculture – were pushed into

cities, where they came to rely more directly on the mass-produced

staple cereals, which they now had to buy, and where they provided a

windfall to urban manufactories of desperately cheap labor.

Peripheral nation agricultural production

was being exported, in order to get precious US dollars for use in

international markets and to service external debts. The agri-barons of

the periphery were not feeding their own countries, but engaging in

monoculture for export, like coffee, sugar, and bananas (ergo the term,

“banana republic”).

Urban hunger is a specter that most leaders understand only too well.

I witnessed two food riots when I was in Haiti, and I can say they were among the most memorable experiences of my life.

Political leaders know very well that mass

urban hunger is a recipe for political destabilization, and they avoid

it at all costs. Because many of these nations were exporting crops,

they fell short in providing basic nutrition to their own growing urban

populations.

The United States, however, was uniquely

positioned to take advantage of this situation, because the agricultural

subsidies of the New Deal, originally meant to rescue family farms, had

been carried forward to the benefit of large agribusiness corporations

that were pushing the American family farm into the dustbin of history.

Price supports for US grains meant that agribusiness could produce as

much grain as possible, and for every bushel produced the government

would pay them a subsidy.

This, along with the arable land mass of

the American Midwest, quickly led to massive overproduction of US grain

in the face of periodic grain shortages around the world, which gave US

agribusiness unprecedented pricing power in grain markets.

In 1973, Secretary of State Henry

Kissinger said that the dominance of US grain production in the world

was a foreign policy weapon that was more powerful than nuclear bombs.

Henry Kissinger

Grain was on a lot of political minds those

days. Hubert Humphrey, the 1968 Democratic challenger for the

presidency, had received an illegal campaign contribution of $100,000 – a

fact that would emerge during the Watergate hearings. The same

contributor would also give the Nixon administration $25,000 to assist

in its cover-up of the Watergate break-in. These were not insubstantial

sums then, as they seem now.

Not many people had then heard of this

fountain of largesse, whose name was Dwayne Andreas. Andreas pushed

through a historic grain sale to the Soviet Union for the Nixon

administration, worth $700 million, with his company as the middleman.

That company was named Archer Daniels Midland.

It was the next year, however, when Green

Revolution food production was exposed to another vulnerability, the

aforementioned Arab oil embargo.

It is here that we can see how the history

of the Green Revolution as an instrument of US foreign policy

interweaves with the history of neoliberal finance – which we covered

earlier – that began its gestation with the Nixon administration.

By 1973, the US was running not a trade

surplus but a deficit of $6.4 billion. Even more momentously and

permanently, US domestic production of crude oil had peaked and was now

known to be in a permanent and irreversible decline that would increase

US dependence on imports of this commodity into the foreseeable future. Oil remained the principle feedstock of American domestic

agriculture, and of the Green Revolution that was articulating the

decolonizing periphery into a new, neo-colonial order. At the

same time, the US would become increasingly dependent on fossil energy

imported from abroad, not merely to power its machines and transport,

but to eat and to maintain the power of the US over food markets

worldwide.

Even the Soviet Union had been pulled into

the American grain-trade orbit by Nixon, proving Kissinger’s thesis that

food was more powerful than nukes.

The increasing dependency of peripheral

nations on American agricultural goods, as well as American support for

the industrial capitalist model being adopted for peripheral nation

export agriculture, would lead to decreases in national per-capita food

production as well as financial and ecological bankruptcy.

Nixon broke up the old order; but the new

order was not firmly established except serendipitously by the Reagan

administration. In the interim, after a period of three years

stewardship of the White House by the immanently forgettable Gerald

Ford, the next elected president would have a dual-resume: a Naval

officer and an agribusiness CEO.

Under Jimmy Carter, a southern agribusiness

plutocrat posing as a good ol’ boy (a peanut “farmer”), an interesting

thing happened. Something we Southern folk used to call “white liquor”

or “white lightning” became legal and began magnetizing massive cash

flows from US taxpayers in the form of corn subsidies.

Corn liquor has been produced for many

years by rural scofflaws. My own father did a short stretch in the

hoosegow when he was discovered with a car trunk full of it in the

1930s.

When Nixon was taking money from Dwayne

Andreas, the CEO of the sugar and corn conglomerate, Archer Daniels

Midland, ADM was concocting a new scheme that would simultaneously

justify more “farm” subsidies to agribusiness and claim to address the

“energy crisis” of 1973, which was also such a windfall to Wall Street.

The scheme was to make massive quantities of corn liquor, which is of

course flammable, and re-christen it “ethanol.” This was proposed as an

“energy independence” measure for the US. It is made, naturally, with

sugar and corn.

ADM found a friend in Jimmy Carter.

Carter called the energy crisis the “moral

equivalent of war,” and his administration exempted ethanol-spiked

gasoline from a federal fuel tax.

Carter began a loan program to build

ethanol plants, which was halted by the Reagan administration… for a

while, until farm lobbyists paid serial visits to Capitol Hill,

whereupon the Reagan administration recanted.

To this very day, neither party will challenge agribusiness subsidies; and to this day, both parties are avid ethanol boosters.

It was this influence, in conjunction with

neoliberal “free trade” policies, that allowed US grain producers to

begin a process called agricultural dumping. Dumping is introducing a

surplus into a foreign market below market value, which results in local

producers’ inability to compete. Taxpayer-subsidized US corn, for

example, is still routinely dumped into foreign markets at prices often

as little as 30 percent of market value. This leads to bankrupted

local markets, and a growing and increasingly poor urban population that

becomes hostage to an imperial food market.

A Mexican farmer who grows traditional corn

is wiped out by genetically modified, chemical-industrial corn that is

subsidized by a foreign power. His family loses their land to debt,

moves to the city, where they may or may not find work to get money to

feed themselves, and barring that, they may take the risk of illegal

migration to the north to find work in the United States. One seldom

hears about neoliberalism or agricultural dumping when the subject of

illegal immigration comes up in the United States; but the connections

are clear. US policies have created the conditions that make mass

migration inevitable.

After many NAFTA provisions went into

effect that allowed US dumping in Mexico, between 1997 and 2004,

taxpayer-subsidized US corn exports increased by 413%, while Mexican

corn production fell by 50% based on a 66% devaluation of Mexican corn.

In the same period, US soybean production increased by 159%, and

Mexican soybean production decreased by 83% based on a 67% devaluation.

Mexican pork production fell by 40%, corresponding to a 707% increase

in US exports. Pork itself is not directly subsidized, but the corn

that feeds industrial pork is. It is not a coincidence that NAFTA

corresponds to the most massive wave of Mexican immigration to the

United States in history.

So the combination of developmental

imperatives to mechanize and enclose agriculture for monocrop

production, as well as agricultural dumping by the United States has

created a situation where most of the rapidly urbanizing world is now

dependent on US grain or US seeds and chemicals in order to eat. US

foreign policy pertaining to food has become what the late Ivan Illich

called “a war on subsistence.” The androcentric cliché for holding

power over others as “having them by the balls,” might better be

replaced by “having them by the bellies.”

US international power politics combines

the neoliberal debt traps with food monopolization as an effective

mechanism of indirect control over a good deal of the globe. This is

not, however, sufficient to exercise the kind of total dominance the US

would require to halt the very real decay of US power that results from

various kinds of imperial over-reach. The debt system is not

sustainable. The energy system upon which the current system depends is

not sustainable. The material resources upon which economic expansion

is based are finite. And the tolerance of others is reaching its

limits.

The fallback position of any imperial

power, when indirect controls are no longer effective, is direct control

in the form of violence. That is one of the reasons the United States –

with some of the best naturally defensible borders in the world, and an

impossibly large land mass for any would-be invader – maintains a

military force that is more expensive than the combined military forces

of the rest of the world. Calling the War Department the Department of

Defense is perhaps the most ironic example of PR-speak you might

encounter. The US military is almost exclusively dedicated to missions

of aggression abroad.

Moreover, the force component of US foreign

policy is not merely the uniformed services, it includes a shadowy and

well-financed covert operations component that allows military actions

by US-directed surrogates to provide an element of plausible deniability

to US actions that might undermine ideological claims of commitment to

principles like “freedom,” “human rights,” and “democracy.”

Neoliberal theology asserts the primacy of

the private, the value of small government; but neoliberal practice has

been massively underwritten by the state. The assurance of the market

economy – as Karl Polanyi pointed out almost 70 years ago – requires a

network of regulatory institutions. Without the state’s affirmative

actions on behalf of the international business class, the system would

collapse. Begin by thinking about how six battle groups from the US

Navy are required to ensure the flow of fossil hydrocarbons into the

industrialized metropolis, and you can extrapolate from there.

The failed attempt to conquer Iraq in 2003,

while it certainly involved oil, was also part of an effort to maintain

a forward deployed US military capable of strategic intervention far

from home. The Cold War had ended, and the disposition of US military

forces had become obsolete. They needed to be redeployed from positions

that were calculated to contain the USSR into positions that would give

the United States more capacity to intervene in energy-rich Southwest

Asia, to put the imperial hand – as it were – on the spigots of global

energy.

The goal of the Iraq invasion was permanent

bases; but instead the Bush administration managed to win the Iran-Iraq

war on behalf of Iran. The Obama administration has decided that the

next best thing is to forward base near the Middle East and in the

Asia-Pacific Theater to prepare to contain China; and the Obama

administration has vastly expanded the role of the covert operations

forces, as well as armed mercenaries, in its expansion of the

Afghanistan War into Pakistan and increased covert operations against

Iran.

Obama’s administration was instrumental in the execution and consolidation of the coup against the democratically elected president of Honduras in 2009, just as the Bush administration

was in the failed coup against the democratically elected president of

Venezuela in 2002, and its successful coup against the democratically

elected government of Haiti in 2004. In two cases, the offending

parties – President Chavez of Venezuela and President Zelaya of Honduras

– were guilty of defying the Washington Consensus, that is, of opposing

neoliberalism. President Aristide had merely criticized neoliberalism.

More than strategic interests drive the

reliance on military operations. In the United States, the Department

of Defense has become a substitute export market for US industries. The

reason the taxpayers are not bailing out Lockheed Martin, Northrup

Grumman, Boeing, General Dynamics, Raytheon, KBR, L3 Communications,

SAIC, Dyncorp, Hewlett-Packard, and a host of other major American

corporations, including General Electric, Motorola, Goodrich, and

Westinghouse, is that the margin of earnings that ensure their continued

viability as capitalist enterprises comes from DOD contracts. If war

spending were ended tomorrow, the US would experience a dramatic loss of

jobs across a wide spectrum of Congressional districts that have

hitched to the DOD pork wagon.

American foreign policy is amphibious. It

operates through both the wet depths of public institutions and the dry

lands of private institutions, and it has an integrated public-private

perception management apparatus.

One of the key advantages of the

public-private partnership is that foreign policy is insulated from

accountability to those below those institutions on the social

hierarchy. The boundaries are blurred, via contracts and memoranda of

understanding, between the US public sector – with its administrative

apparatus, and its military and intelligence establishment with their

vast budgets – and the private sector, composed of publicly funded

“non-governmental organizations,” think tanks, foundations, and an army

of horizontally-integrated perception managers.

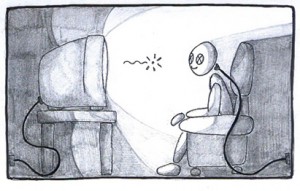

Those perception managers use mass media as

a conformity-producing web of influence that reaches right into the

living rooms of a US culture that has 2.24 television sets per

household, running an average of six hours and 47 minutes a day, 2,476

hours a year. To appreciate the latent power of television, realize

that the average college class has a student in tow for three hours a

week, approximately 45 hours for an entire course, excluding

out-of-classroom study.

The limits of public discourse are

established de facto by a media that operates on the same liberal market

principles as the people who own them and exercise hegemony within the

government and in those sectors sometimes called civil society. The

media, the governing apparatus, and civil society are in fact three

faces of the same dominant interests in the same epoch.

In saying this, I am obliged to clear up a

common misunderstanding of what this means and what I mean to say. It

is easy to jump from the very general outline I have presented of three

aspects of US foreign policy – finance, food, and force – to the

conclusion that I mean to say, or that these facts tend to support the

idea that, there is a conscious group of the conspiring powerful who

direct the world. On the contrary, I want to emphasize that this system

has evolved through a series of contingencies, and that its

stability is maintained precisely because it is what some systems

theorists call self-organized. It’s most powerful actors are in many

ways as constrained, or more constrained, by neo-neo-liberalism – or

whatever you choose to call this particular period – than most of us

are. President Obama is far less free, for example, to say the kinds of

things I can say here as an unemployed grandfather.

I, on the other hand, do not have the legal power to send US troops to war, or to call them home.

We each play our parts, and while some

conspiracies have always been part of the terrain of politics, they are

generally reactive, and far less determinative of large-scale outcomes

than, say, changes in the built environment, demographic shifts, or

institutional inertia. Many of the most pivotal events in history

emerge unexpectedly from long-standing trends that have gone unnoticed

or ignored until they reach a breaking point – the 2008 housing bubble

crash being a good recent example.

Remember, in our saga about the birth of

neoliberalism, there was no straight line, but a confluence of events

and contingent decisions: French buying US gold, Nixon dropping the

gold standard, the Egyptian war for the Sinai, the American decision to

airlift TOW missiles to the Israelis, the decision of Arab oil producers

to embargo oil to the US, the US balance of payments deficit, Nixon

drops fixed currency exchange rates, rising oil prices creating

petrodollars, the petrodollar tsunami being converted into opportunistic

development loans, the Mexican threat of default, and so it goes.

These were not plots, but actions and reactions, each producing a number

of unintended or unanticipated consequences, which stimulated new

actions and reactions.

The belief in a conspiratorial view of

history seems to me to be a psychological reaction to the fear of

chaos. If the world is not as one would like it, at least a

conspiratorial view of history suggests that history as a process is

still subject to human control, and that once we wrest control from the

unjust conspirators, the world can be made right again. Far too often, the conspiracy-fetish turns finally on the perennial scapegoat - Jews.

This unpredictability, this sense of

instability that compels some of us to reach for order in chaos with a

history of conspiracy, ironically, has been produced by the current

political milieu, one wherein neoliberalism has disembedded economies

from local control and re-embedded them in national and transnational

institutions, and those institutions are themselves now experiencing a

loss of control in the face of unanticipated changes.

Structural adjustment programs have become

political lightning rods that are igniting mass unrest around the

world. Green Revolution agriculture has spawned megacities that are

entropic black holes, teeming with desperation and crime. The US

military, long considered the guarantor of last instance for the world

order, has proven to be both the least cost effective institution on the

planet and a perennial source of new resistance and unintended

outcomes. In Iraq and Afghanistan, the myth of US military

invincibility was shattered; and the costs of the Southwest Asia wars

have bled the US Treasury white. Offshoring of US industry and the

political empowerment of rentier capitalists – Wall Street – that was

accomplished through foreign policy, has transformed much of the US

domestic population not merely into wage workers, but debt slaves.

Consumer debt in the United States is above

$2.4 trillion. In 2010, consumer indebtedness amounted to $7,800 for

every man, woman, and child in the United States. 33% of that debt is

in revolving credit, that plastic you carry in your pockets. The rest

is in mortgages, student loans, automobile loans, and other

non-revolving credit schemes. You students collectively owe $556

billion dollars. Good luck with that.

US household leverage, the ratio of debt to

disposable income, was 55% in 1960. By 1985, that number was 65%.

Today, household debt is 133% of household disposable income.

Yet when the crisis of fictional value

created by Wall Street came home to roost, trillions in bailout money

were awarded to Wall Street, while Main Street was left holding its

debts. Wall Street, according to the experts who work the Wall

Street-Washington nexus, was too big to fail. Generations into the

future are now saddled with paying for these bailouts. We are being

structurally adjusted, which has always been a euphemism for privatizing

the gains and socializing the losses.

Would a communistic, resource based economy in which every one works for negative profit (a loss), solve economy problems relating to thermodynamics?

ReplyDeleteICC Mortgage And financial Services,Is a sincere and certified private Loan company approved by the Government,we give out international and local loans to all countries in the world,Amount given out $2,500 to $100,000,000 Dollars, Euro and Pounds.We offer loans with a dependable guarantee to all of our clients. Our loan interest rates are very low and affordable with a negotiable duration.

ReplyDeleteAvailable now

MORTGAGE, PERSONAL, TRAVEL, STUDENT, EXPANSION OF BUSINESS AND NEW UNSECURED, SECURE, CONSOLIDATE

AND MORE

Available now..

Apply for a loan today with your loan amount and duration, Its Easy and fast to get. 4% interest rates and monthly

installment payments.

{nicholasbrush.icc@gmail.com}

Regards,

Nicholas Brush