This is an examination of "just war" doctrine for Roman Catholics, though many confessions claim to subscribe to some "just" war notion. First, a little history.

In exploring the Civil War through moral lenses, one sees just how unprepared Americans were for such a cataclysm in the moral sense no less than the military or political. And unlike politics and military arsenals, which geared up to meet the challenge, the ability to fix a moral stance never progressed. Rather, it regressed. On all sides – clerical, political, journalistic, military, artistic, and intellectual – the historian searches in vain for moral criticism directed at one’s own cause. Talk of war certainly bristled from the pages of the secular press and civic assemblies, the statesmen, clergy, and intellectuals raged against the unjust conduct of the enemy.-Harry S. Stout, Upon the Altar of the Nation – A Moral History of the Civil War (Penguin, 2006)

The Civil War was

fought during a period of rapid industrialization. The railroad, the telegraph, aerial

reconnaissance balloons, submarines, ironclad ships, rifling of firearms and

artillery, and manufactured goods like clothing and equipment, were all introduced

together in the American Civil War in a particular way that marks that war as

the first “modern war.” The Civil War

was also our first “total” war.

At certain thresholds

of scale, in any enterprise, the change in quantity forces changes in

quality. Qualitative changes are not

always or even usually predictable. What

manufactories and rail lines did was provide the conditions for fielding

immense numbers of combatants. It tied

these vast armies to these new lines of communication and supply, changing

every strategic calculus from the past.

The companies that supplied the materiel became rich and powerful in

their own rights, as did the rail companies.

To finance the output of war materiel, industrialists needed credit, and

so haute finance also found that the war strengthened them. The knock-down effects of this new modernity

of war were felt everywhere as change.

The large sizes of

military units, their training in a now obsolete Napoleonic doctrine, and the

unanticipated effects of rifled barrels at close range, turned Civil War engagements

into rivers of blood.

As Harry Stout’s moral

account of the Civil War notes, the modern governing apparatus – in its

hegemonic partnership between nation-state and “civil society” – was already

taking shape as something recognizable to us today. The specific kinds of relations and

interdependencies that characterize the modern politics of war can be seen in

Stout’s description above.

We need only think back

to the run-up for the past several US military adventures to see that network

and echo chamber that includes “the secular press and civic assemblies, the

statesmen, clergy, and intellectuals” of the United States.

I once taught “military

science” at the United States Military Academy at West Point. First year military science included the freshman’s

obligation to commit to memory the principles of war developed by

Clausewitz. Those principles were

memorized by using the mnemonic MOOSE MUSS:

Mass, Objective, Offensive, Security, Economy of Force,

Maneuver, Unity of Command, Surprise, Simplicity.

Stout

calls West Point the first seminary of American nationalism’s civil religion.

The primacy of war as

the raison d’etre of the modern

nation-state is discernible by law.

Using the United States as an example, the one office that cannot be left

unfilled for even a day is that of the Presidency. The reason is that the absence of one

commander-in-chief of the armed forces creates an unacceptable risk of the loss

of “unity of command” – a principle of war listed above.

Centralization of authority has always been integral to war, a precondition of war, and it generates the temptation to war.

Destablized Men and Worship

Masculine roles were changing in the 19th century; the southern ideal of manhood was beginning to become obsolete in the face of the new Self-Made Man of the Market Revolution. In order to protect their homes and preserve their manliness, Southern men embarked on the bloody affair known as the American Civil War.

American flags are

posted in the front of almost every Christian church sanctuary in the United

States.

Prior to the Civil War,

the only time most residents of the United States would see a national flag was

on ships. The stars and stripes were

neither icon nor idol. With the quasi-religious

calls on either side of the Civil War to defend their respective civil

religions – their nationalisms – the status of the flag took on the religious

significance of both. Stout describes

the apotheosis of the nation symbolized by the flag.

All this changed in 1861. The clearest and most literal emblem of patriotism and resolve was the national flag. Churches, storefronts, homes, and government buildings all waved flags as a sign of loyalty and support. A nation festooned with flags is a nation at war. (Stout, p. 28)

This description could

well have been the US immediately after the attacks on the World Trade Center

in 2001. For a time, people were

displaying flags out of fear that they would be ostracized from their

communities or held in suspicion if they failed to display flags. The prevailing attitude among the most vocal

national boosters included the President of the United States and

Commander-in-Chief of the Armed Forces, George W. Bush. Where Jesus had once said that “those who are

not against us are with us,” the President flipped the script and ominously

told the nation, “you’re with us, or you are with the terrorists.”

Another scale-shift

innovation of the Civil War was the incorporation of mass media into the

public-private war partnership. Steam

presses that printed penny papers were ubiquitous, especially in the

North. They were micro-enterprises, and

their content created a limited demand.

But with “war and rumors of war,” steam press publications started

selling out on the streets. It became

clear to the newspapers, like the New York

Herald and the New York Tribune,

that war – for the press – is outstanding business.

Mass media met war

profit, and the first press agency – the Associated Press – was formed in New

York City. The more strident (and

masculine!) the papers’ voices in support of war, the more copy they sold.

April 19, 1861, The New York Tribune wrote:

The defection of Virginia shows that little can be hoped for from the loyalty of the dominant party in the Border slave states, and the Government should prepare for a great war. At least 200,000 men should be called out in addition to the regular army.

Modern

mainstream media has evolved into something very different from the

emergent media during the Civil War.

They had no access, of course, to the suggestive power of television or

the hot-sheet information-flow of the internet, nor had the media yet become

transnational for-profit corporations, nor had they the demonic sciences of Bernays and his intellectual offspring.

Their service for pay in support of the war, however, was the germination

of the modern relationship between media and war. The media would translate the war to the

public as titillation, jingo patriotism, fantasy projection, and entertainment. Think CNN.

Unbeknownst to the

participants in this event, they were setting the stage for the Age of

Simulation – an age into which we ourselves were all born.

Propaganda has long

been integrated into war. But again, the

vastly expanding scale of enterprise that characterized the rise of modernity

gave rise to qualitative change – phase shifts during which more effective propaganda

was reaching homogenous (white, male) masses.

Because this profit-making aspect of the media required greater and

greater spectacles and more and more salaciousness to continue to whet the

appetite of a consuming public, mass media turned out to be highly volatile. Baudrillard would later call this volatile

mix of re-interpretation “hyper-reality” – proxy or “virtual” reality.

The Charleston Mercury

would write in April, 1861:

The matter is now plain. State after State in the South sees the deadly development, and are moving to take their part in the grand effort to redeem their liberties. It is not a contest for righteous taxation. It is not a contest for the security of slave property. It is a contest for freedom and free government, in which everything dear to man is involved.

Stout wrote that moral

and religious language was placed in the service of the cause – whichever side

you happened to take. Stout says they

were “subordinated to war, honor, and manliness.” One of his examples was a Southern editor.

The South fights… for honor, character, standing, and reputation. She must not only wipe off the stigma of effeminacy with which Abolition has branded her, but she must prove that she possesses the high-toned chivalry, that enduring and indomitable courage that is peculiar to a privileged caste. (italics added)

Again, as is usually

the case, historians (with a few feminist exceptions) have recorded the

gendered language, but seldom draw the conclusion that masculinity is a

particularly important factor in understanding history.

The construction of the

Southern male, based on honor, and defined against blacks – who Southern white

men defined as lacking honor, meant that any attack on slavery was a direct

affront to Southern manhood. As JacobFriefeld notes:

And so the duel was on, and it would become a monumental bloodbath, as well as the most costly war in history, still, as counted in loss of US life.

To take away that against which honor was defined was to take away the Southern man’s honor and therefore his manhood. Furthermore, characterizing slavery in a negative light… was a manipulation of the Southern man’s world of appearances. The man of honor portrayed slavery as a positive institution; to characterize it in any other way was a form of giving a Southern man a lie, a situation that called for a duel.

And so the duel was on, and it would become a monumental bloodbath, as well as the most costly war in history, still, as counted in loss of US life.

While the build-up for

the war seized the consciousness of men North and South, the clergy of the

large churches fanned the flames of war from the pulpit – North and South

arguing that Christ was on their side.

The church had become

the captive of the surrounding culture yet again.

Re-Weaponizing Christ - It's a Man-Thing

Northern and Southern

white masculinity differed inasmuch as Northern hegemonic masculinity was

formed in the image if Victorian manhood, and Southern hegemonic masculinity on

a more Continental and archaic honor-based manhood (note the reference above to

chivalry, and that the KKK calls itself the KNIGHTS of the KKK).

On the other hand, they had a great

deal in common, having gone through both the Revolutionary War – based on the

principles of republican manhood – and the success of the expansionist war

against Mexico.

The Mexican War, in

which most of the generals on both sides of the Civil War had made their prior

reputations, was underwritten by a nascent imperial masculinity that narrated

Westward expansion as a providential mark of progress. This expansionism privileged a frontier

masculinity based on a probative contest between civilized men at arms and a

wild, chaotic nature – which also included the less-than-fully-human inhabitants of the coveted land.

That

frontier masculinity is still a powerful cultural trope in the United States,

as evidenced by our undying attraction to the film genre of Westerns. Nearly every American white man my age played

Cowboys and Indians; The Indians, like the wilderness, the wolves, and the

harsh weather, were mere backdrops in the articulation of this masculine ideal.

The generals of the

Civil War had not only fought the Mexicans, they were indoctrinated in West

Point, where the national religion was based on the Revolutionary narrative –

independence – which was sealed by the blood sacrifice that sacralized the

United States.

Cowboy tropes were

deployed frequently during the George W. Bush administration; and they

connected with great force to a significant fraction of US males.

So while the urbane

Northern men and the aristocratic Southern planters each had a distinct

cultural identity, they both shared a lineage of masculinity that passed

through Jeffersonian and Jacksonian republican ideals of masculinity – with its

emphasis on independence as the mark of full male citizenship. Moreover, both groups of men in leadership

roles measured themselves, as men, against two general groups of people: non-white (which included some European

immigrants) and women.

So, instead of seeing each other as two sections with very different worldviews, Northern and Southern men looked upon each other as being similar parts of one nation based on their common independence, superiority to black peoples, and their differences from women. Consequently, when the crisis of secession reared its head, Northerners and Southerners did not see each other as two different cultures attacking an opposite worldview; instead they looked at each other as having absurd views within a shared value system and the two sides communicated as such. When the two regions collided in sectional conflict, they used arguments that appealed to a perceived shared masculinity while the meanings of their arguments were transformed through cultural translation and were misinterpreted. Such misinterpretations often made Northern rhetoric more inflammatory to Southern men of honor while diminishing the ferocity of Southern rhetoric in Northern eyes. linkAs we saw above, a duel is what the honor-masculinity of the South wanted, and secession was the ritual slap in the face that would inaugurate a duel. Friefeld calls Northern insensitivity to Southern honor codes their “illiteracy in the language of honor.”

The mercantile Northerners were calculators, the embodiment of Enlightenment disenchantment. They could not understand why Southerners were insulted by Northern offers of monetary advantage in exchange for keeping the union. In many cases, the Northern argument against slavery had no hint of moral content – it was seen as inefficient compared to a system of “free labor,” which could be controlled not "paternally," but by the pangs of hunger and the all-to-human enslavement to desires.

The reactionary South

had become the last drag on the emergence of the new nation-state, conceived in

war and now about to be consolidated in war.

Several Southern states had seceded, thereby upholding their Southern honor and preserving their manhood through a duel. Meanwhile, the North, controlled by Republicans, refused to surrender forts or ports to the Southern gentlemen based on their own ideas of an indivisible Union and economic stability. More states would eventually secede, but both sides, operating within separate frameworks of manhood, had already started their journey on the confused road to war. (Friefeld)

In this confusion, a

new iteration of Southern masculinity was about to come to the surface, again

supported by Southern clergy. This newer

masculinity was based on the fear of reversal, the fear of black rule. In the white Southern male mind, the honorable

Southern man was about to be victimized.

He began to see himself as a victim of Northern aggression (and by extension, of Negroes), in which the

North was portrayed as treating the South as its black slave. Rather than expose the contradictions in

these ideas, this comparison only further inflamed the Southern martial

imagination. When the war would be lost,

this sense of victimization and its attendant fear of black political power

would shape the murderous masculinity of the Ku Klux Klan, openly valorized as

heroes in the United States well into the 20th Century.

The threat of this role

reversal was understood fundamentally as the threat of feminization. The counter to feminization is masculinity

proven under arms, the vigorous life of the frontiersman or soldier.

First Taste - Exterminism

War, then, has within it the seeds of good, seeds which must be fertilized by blood to bring forth a harvest of blessings. And if ever there was a war that demanded at once the energies of the patriot and the benediction of the Christian, it is a war in defense of homes and altars, of civil liberty, of social virtue, of life itself, and of all that makes life worth living.

The actual Civil War was

not a duel; it was a charnel house. It

was the merger of mass technologies of efficiency with warfare, and human bodies paid the shocking price.

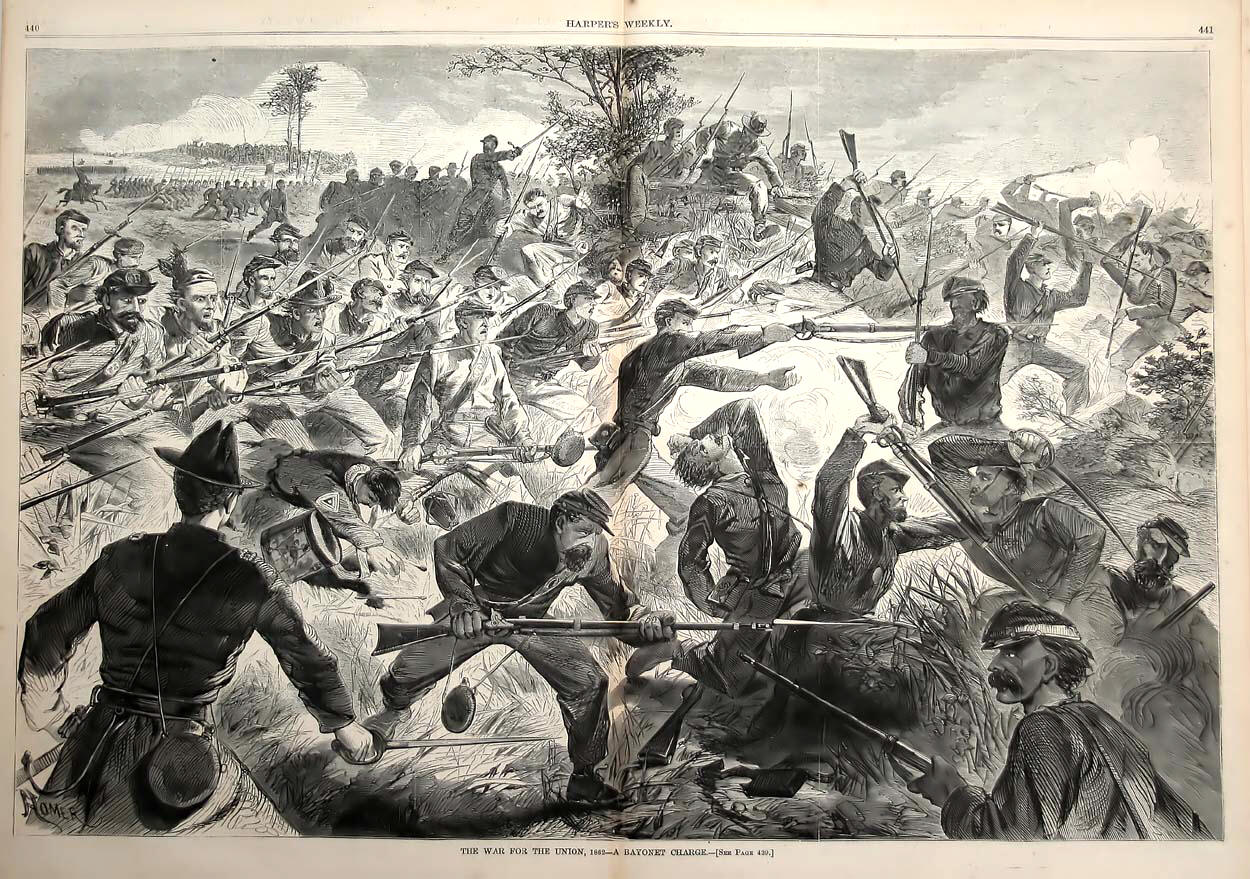

The West Point

graduates who were directing troops were schooled in the frontal assault, which

was effective in the Mexican War. The

frontal assault was always finished with a bayonet charge, which became a

masculine icon within the tactical repertoire – every officer wanted to be

there for a successful bayonet charge, at least in his imagination. Military men are typically resistant to

change, often to the point of brutal stupidity, and digging in for the defense

was seen as effeminate. Even after a series

of frontal assaults against entrenched defense had racked up corpses by the

tens of thousands, the Generals continued with their bloody anachronism – even

to be celebrated on the home front based on the number of lives lost in

battles. The greater the numbers, the

greater the battle, the greater the glory in the service “off all that makes

life worth living.”

The observation of one

battle by General Evander Law at Cold Harbor, Virginia, where the casualty rate

exceeded 116 men a minute, led the officer to say, “This was not war, but

murder.” The battle he witnessed, by the

way, accomplished little for either side.

Law was seeing

firsthand the exterminist face of modern war, and the boundary between murder

and war was again effaced, this time with ever-increasing, industrial efficiency.

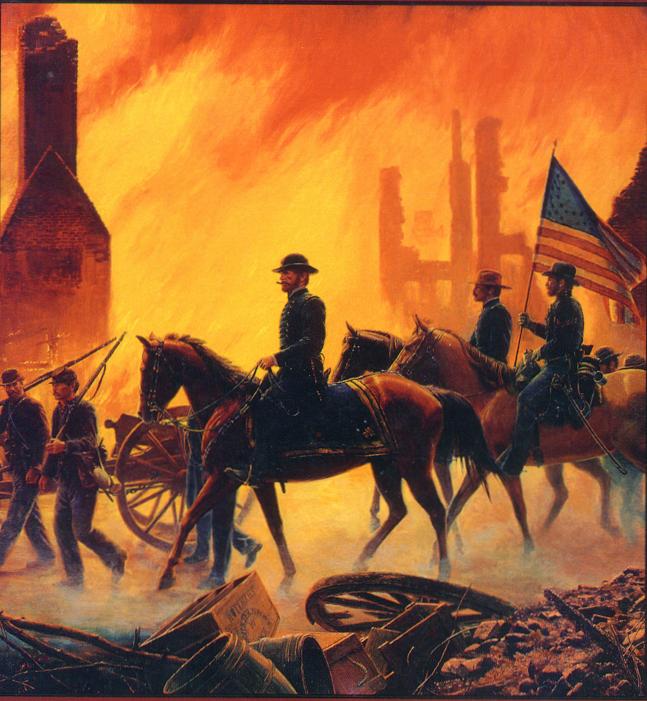

General William

Tecumseh Sherman’s name would be associated in history with ruthlessness, both

in the Civil War, where he intentionally took the war to Southern civilians,

and after the war as a proponent of Indian extermination. But Sherman was a late-comer. The first modern general of the war was General

Thomas “Stonewall” Jackson, the hero of the Battle of Bull Run and terror of

the Shenandoah. With the legend of

Jackson came the valorization of the modern General as a masculine

archetype. His subordinate commander,

General Alexander Lawton, described him thus:

He had no sympathy with human infirmity. He was a one-idea’d man. He looked upon broken down men and stragglers as the same thing. He classed all who were weak and weary, who fainted by the wayside, as men wanting in patriotism. If a man’s face was white as cotton and his pulse so low that you could not feel it, he merely looked upon him impatiently as an inefficient soldier and rode off, out of patience. He was the true type of all great soldiers. The successful warrior of the world, he did not value human life where he had on object to accomplish. He could order men to their death as a matter of course.

It would be difficult

to find a more direct passage from a practitioner of war that highlights the

contrast between men of war and Jesus Christ, God who sanctified human life as

an enfleshed human being and commanded us to love both neighbor and enemy.

By the time of the

Civil War, the separation of Christ from the world, and his relegation to some

cosmic realm separate from human experience, was accomplished. War demanded this separation for those who

professed the Kingship of the risen Christ, and war - the liturgy of the nation - would win out.

Stonewall Jackson

frequently gave the order to his men before battle: no prisoners.

The massacre mentality of the Crusades had returned, but now American

Christian was killing American Christian.

God had become an emotional appendage of the war.

The proportionality

that had been a criterion for “just war”

had evaporated. Sherman’s great campaign

of arson through the Southern hinterland was morally established by Jackson,

and by the patriotism-inflamed approval of this new form of war on both sides

of the struggle. Blood was the

fertilizer for blessings, so a lot of blood would fertilize a lot of blessings. And the church was captured within two

competing nationalisms, an objective demonstration of how nation came to trump

Christ.

After setbacks,

national fast days were announced on either side to get back into the good

graces of the Lord; but these national days of fasting were also consecrating

the nation as the civil religion, which was being forged in a blood

sacrifice. The great traditions of the

church were echoed – by design – in the national rhetoric of both sides, to create

the aura of sanctification for the nation – the new god; and technical

efficiency that swallowed up thousands of lives.

Luther, in

1524:

Let no one dare think that the world can be ruled without blood. The secular sword should and must be ready and bloody, for the world will and must be evil. Thus is the sword God’s rod and vengeance on it.

Lincoln was among the

most bloodthirsty, praising Grant even after great casualties as a General. “He fights,” said Lincoln. The famous reticence of McClellan has been

attributed to cowardice, though McClellan comported himself well on the

battlefield, and to ambition. But his

primary reason for resisting Lincoln’s orders was that he believed in just war

as articulated by the Christian philosopher Thomas Aquinas; and he saw clearly

that the battles of this war were being conducted in a way that was not

“proportional.” The treatment of the

enemy was out of proportion to the wrong, and the acceptance of civilian

casualties as the cost or war (later to be called “collateral damage” to take

the moral sting out of it).

Wrote McClellan:

Wrote McClellan:

[War] should be conducted upon the highest principles known to Christian civilization. It should not be a war looking to the subjugation of the people of any State in any event. It should not be at all a war upon population, but against armed forces and political organization. Neither confiscation of property, political executions of persons, territorial organization of States, or forcible abolition of slavery should be contemplated for a moment. In prosecuting the war all private property and unarmed persons should be strictly protected, subject only to the necessity of military operation.

His refusal to see the

issue of slavery as decisive for war was shared by most Northerners, even as

slavery was the structural contradiction that gave rise to the war. Northern Democrats were already arguing for

white supremacy and post-war apartheid, even if slavery were abolished. McClellan’s reluctance to embrace modern war,

however, for its inhering lack of proportionality, was decisive for losing his

job as Commander of the Army of the Potomac.

When Lincoln did

replace McClellan, he sent in General John Pope, a veteran of battles in the

West where his cruelty and punishment of civilians was as legendary as his

tactical acumen was mediocre. He gave

the impression of being fierce, and was known as a braggart. Lincoln would learn, when Pope was defeated

at the Second Battle of Bull Run, with the loss of 10,000 men, that total war

would not be accomplished by a fierce demeanor, but by calculating sang-froid.

Cold instrumentalism

would be the new master of war, and war was the new master of modern society. In Lincoln’s own words, when questioned about

his prosecution of the war:

What would you have me do in my position? Would you drop the war where it is? Or would you prosecute it in future with elder stalks squirts charged with rosewater? Would you deal lighter blows rather than heavy ones? Would you give up the contest, leaving any available means unapplied? I am in no boastful mood. I shall not do more than I can, and I shall do all that I can, to save the government, which is my sworn duty as well as my personal inclination. I shall do nothing in malice.

(Basler, Abraham Lincoln: His Speeches and Writings, 650)

“What would you have me

do in my position?” The office and his

oath are his lodestar, as in a modern bureaucracy. We mustn’t forget that Lincoln was, like Jean Bodin and the scribes of the New Testament, a lawyer.

He said nothing in

malice. This is a far cry from the

spirit of the bayonet that thrilled the graduates of West Point. Off the record, there is no talk of God’s

providence in the war, but instead an instrumentalism that is summed up as, I

will deal as many heavy blows as I have to in order to maximize my efficacy

[Lincoln says “all that I can, and no more than I can] in pursuit of the war.

Faced with his own embarrassing defeats and unimaginable losses at First Bull Run, Shiloh, and the Seven Days’, Lincoln and his Northern commanders came to the shared understanding that limited war would not work. (Stout, p. 140)

The war had not taken

on the character of insurrection/counter-insurrection, but the character of a

war between two separate nation-states, in which victory would require attacks

against the whole enemy society.

Total war meant a war that put civilians immediately at risk. Total war to transform society meant conquest and occupation by a president who, in 1848, had vigorously protested the Mexican War because, in his own words, it was a “war of conquest” that “places our President where kings have always stood.” A mere fourteen years later, Lincoln was placing himself in the same position for a different cause. (Stout, p. 140)

The Emancipation

Proclamation was part of this very decision, and was conceived of as an

instrument of war – an economic attack against the South. No part of what went before the Emancipation

Proclamation can effectively negate the fact that manumission was a good thing;

likewise, the goodness of manumission in no way excuses any of the cruelties or

violence that contributed to the milieu in which manumission happened. The point here is to emphasize how modernity

and total war were conjoined twins, and how formative that has been of American

culture and American masculinity (and church!).

The Stillbirth of Just War

In Lincoln’s defense,

as the war continued, he turned more and more away from his republican

convictions – which were shattered by the war – and to prayer and meditation to

understand if there might be some special and providential outcome for the

shockingly horrific war.

What Lincoln did even

before the signature appointments of Grant and Sherman – the latter, a former

banker, would embody strategic instrumentality and total war perhaps more than

any other figure – was to give his approval to “foraging,” that is, army units

could steal from local populations.

Pope’s troops terrorized their way south to the final defeat at Second Bull Run; and the war took a new turn. There were no longer any such things as non-combatants. The arson of homes was added to the tactical repertoire, as was the summary execution of suspected guerrillas. For me, this foreshadowed my own experience as a 19-year-old in Vietnam.

Pope’s troops terrorized their way south to the final defeat at Second Bull Run; and the war took a new turn. There were no longer any such things as non-combatants. The arson of homes was added to the tactical repertoire, as was the summary execution of suspected guerrillas. For me, this foreshadowed my own experience as a 19-year-old in Vietnam.

Once these tactics were

inaugurated, both sides engaged in unspeakable cruelty and a series of actions

that can be called nothing more or less than crimes against humanity.

The association of

distinctly modern instrumental military leadership with the apparent anarchy of

pillaging soldiers appears as a paradox, until one realizes that this state

of anarchy – of arson, pillage, murder, and rape against “enemy civilians” –

was used as an early weapon of mass destruction, because the psyche of the enemy must be destroyed as surely as a tactically-significant bridge or armory.

Terrorizing populations wasn’t as instantaneous as an artillery volley; but the result was the same – and commanders had the ability to use this

capacity in a tactical way. In this

sense, too, we see the co-emergence of total war and modernity in the American

Civil War.

At Antietam, during the

Second Battle of Bull Run, the mix of archaic tactics with new weapons

technology left more than 24,000 dead in a single day – the greatest American

military loss of life in a single day in history. The battle itself accomplished little for

either side. It was a warm September,

and war diaries describe the bodies bloating beyond recognition in a single

day.

A month later, in

Memphis, General Sherman would react to hit-and-run guerrilla assaults against

Union gunboats.

In retaliation, he destroyed the town of Randolph, Tennessee, and issued orders to expel ten families for every boat fired upon. When the next attack came, Sherman immediately expelled ten of the city’s residents and destroyed all houses, farms, and crops along a fifteen-mile stretch of the Mississippi south of Memphis. (Stout, p. 155)

Lincoln’s modern war

paladin was standing by in Memphis. He cared not for the alleged moral purpose

of the war – Sherman hated Jews, blacks, Mexicans, and Indians. His role – this banker turned General – was

to achieve a given result. Full

stop.

Honor no longer mattered; the old

rules about civilians no longer mattered; only the mission. After the war, Sherman called for Indian

extermination as “the final solution to the Indian problem.” Hitler – another modern Commander-in-Chief –

would borrow Sherman’s language for his own special program; and used the US

destruction of indigenous American societies as the model for a Europe without

living Jews.

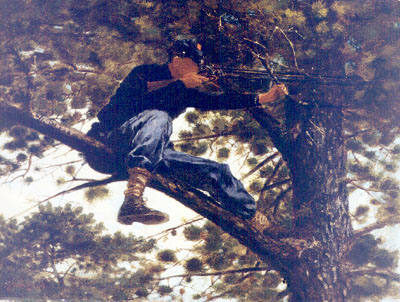

Snipers to Drones

When I was in the Army,

I was designated for a time as a sniper.

I even ran the Sniper Training Program for 2nd Battalion, 7th

Special Forces once. The term sniper in

popular jargon means a single person who shoots at people from a hidden

position. In military parlance, it means

a marksman who can fire at long distances with great accuracy, long distance

being the key whenever possible. In

fact, modern snipers and their earlier counterparts also used a second person

in their position – a spotter – who can look downrange with field glasses or a

telescope and observe the strike of the bullet (the recoil throws the

sight-picture out for the shooter), adjusting for the shooter verbally… “You

are hitting high and left, and he went behind the water barrel” Then the shooter can “hold off” low and right,

aiming center-of-mass at the water barrel.

Ideally, snipers’

positions are never known by their victims (“targets”). In a properly prepared position, a sniper

might fire a shot at enemy troops half a mile away; and if he only fires one

shot, and if he has taken care to prevent flying dust or smoke giving away his

position, the enemy forces cannot determine where the shot came from closer

than about 100 degrees. So it is

difficult if not impossible to “suppress” a sniper by firing near his position

to “get his head down.”

Snipers shoot people

who are too far away to effectively shoot back.

That is really the idea.

Prior to the Civil War,

there was an idea that this tactic was not honorable. It was more akin to murder than combat. Snipers, under ideal conditions, want each

shot to be an uncomplicated, uncontested murder. Align the sights, squeeze the trigger, ride

the recoil. Someone dies. Your spotter will confirm.

General John Sedgwick was directing artillery emplacements at Spotsylvania, shouting abuse

at the Confederate lines 800 yards away in 1864, when a .45 caliber British

Wentworth in the hands of a Confederate sharpshooter fired the bullet that passed through

the General’s head. One shot changes the entire chain of command. That's efficacy in modern war, a real cost-benefit bargain.

When I “worked” in the

Army’s counter-terrorist unit in the mid-eighties, I was first an assaulter,

then a sniper. An assaulter has to break

into a crisis site, and engage his opponents at close range. The tactics for this were called Close

Quarter Battle (CQB). The appropriate

weapons were nine-millimeter submachine guns and semi-automatic pistols.

As a sniper, a good deal of my job was going

to the range, firing from various distances, with various ammunition, in

various conditions, and recording this data in a book that went with each of my

three sniper guns (like different golf clubs).

If a sniper fires during a mission, that single shot is the result of

countless hours of practice and calculation.

One of my colleagues called it “Dial-a-Kill.”

And there is a

difference in distance for the sniper, inasmuch as the sniper doesn’t see his

handwork up close, like an assaulter.

It’s more of a technical specialty.

When I was a sniper, we kidded the assaulters by calling them the

“knuckle-draggers.”

Modern warfare has

generated a new kind of sniper, but the questions about morality that are

raised by sniping remain. That new kind

of sniper is not a trained marksman, but a video-gamer, who pilots remote,

armed drones into position to fire explosives down on the top of people halfway

around the world.

Snipers shoot people

who are too far away to effectively shoot back.

That is really the idea. Drone

warfare has perfected the sniper, except the part about “target discrimination,”

in the bloodless military tongue. Drones

fire guided missiles with explosives.

Explosives cannot discriminate inside of the bursting radius of the

explosives. If the sniper is

dishonorable according to a genteel masculinity, or sinful to a peace-seeking

Christian, when he kills an identified enemy who poses no threat to the sniper,

at least the sniper still adheres to the just-war notion of proportionality –

he can actually – in most cases – ensure that he does not shoot bystanders, and

he knows what is going on in his sector.

He won’t mistake a wedding party for a band of guerrillas. Such is not the case with “unmanned aerial

drones.”

Theologian Stanley

Hauerwas, in the preface to his book, War

and the American Difference – Theological Reflections on Violence and National

Identity (Baker Academic, 2011), writes:

Most Americans don’t seem to be too bothered by the realities of the current wars. It is as if they have become but another video game. In truth, the wars themselves are increasingly shaped by technologies that make them seem gamelike. Young men and women can kill people around the world while sitting in comfortable chairs in underground bunkers in Colorado. At the end of the work day, they can go home and watch Little League baseball. I find it hard to imagine what it means to live this way.

If the ethos of the

sniper evolves into the unmanned drone, the ethos of Sherman, pillaging his way

to the sea to crush the material basis of society, prefigures strategic

bombing. The Civil War let a genie out

that won’t go back in. Modern war, at

the end of the day, is about one thing and one thing only: efficacy.

"Just war" became a checklist for propagandists and government lawyers, a license to play fast and loose with language to make the criteria fit the deeds.

"Just war" became a checklist for propagandists and government lawyers, a license to play fast and loose with language to make the criteria fit the deeds.

Propaganda - War Homily

Another innovation of the American Civil War was photo-journalism; and from the Civil War we have the first widely circulated photo-images of actual war dead. There is nothing like a photo of a wide ditch filled with mangled corpses to take the shine off of war back on the homefront. One thing the frankest of war photography has accomplished, as it did then, is to bring the most profane of realities back from the battlefield and into a civil society that had been intoxicated by the rhetorical sacralization of war. The power of these images was quickly recognized, and in due time, photographs were selected and edited for propaganda purposes, the photo-journalists themselves complicit with their respective governments.

By 1864 both North and South had acknowledged that generals stood as a breed apart, as “brilliant” in the business of killing as philosophers with ideas or painters on canvas. They stood as the warrior priests of America’s dawning civil religion, entrusted with making the sacrificial blood offerings that would incarnate the national faith.-Harry Stout (p. 321)

New York abolitionist William R. Williams, writing

in 1863 for The Liberator, wrote what

can be seen now as an apology for total war, which shifted the rationale for

“just war” from a consideration of legitimate need (self defense, e.g.) and proportionality (protection of

non-combatants, e.g.) to a

utilitarian calculus that justified the means by the nobility of the cause for which the war was fought. As the blood sacrifices of the war mounted

inconceivably, ending slavery became that redemptive rationale. Williams wrote:

[S]ince the object of a just war is to suppress injustice and compel justice, we have a right to put in practice against our enemy every measure that will tend to weaken or disable him from maintaining his injustice. To this end, we are at liberty to choose any and all such methods as we may deem most efficacious.

*

From the issuance of Lincoln’s Emancipation Proclamation on, Americans in the North and South would not look back to restrained codes or charity. Total war, with emancipation as the inner accelerator, meant articulating a war ethic in which civilian suffering could be presumed and morally justified. By the spring of 1863 Lincoln’s legal scholar, Francis Lieber, would complete a rationale for total war that would stand as a new American foreign policy. (Stout, p. 188)

*

At the beginning of the war, Southern pulpits and the secular press had been engaged in a common enterprise: banging the drum for a “Christian” and “manly” war effort. But the strains on the Confederate government in the midst of total war and the social stresses… could not smooth over ideological differences among various factions for long.

For some, “Christian” and “manly” became separated. (Stout, p 210)

*

Chamberlain, the hero General of Little Round Top at

Gettysburg, is quoted (Trulock, In the Hands of Providence, pp. 144-50):

All around, strange mingled roar – shouts of defiance, rally, and desperation; and underneath, murmured entreaty and stifled moans’ gasping prayers, snatches of Sabbath song, whispers of loved names; everywhere men torn and broken, staggering, creeping, quivering on the earth, and dead faces with strangely fixed eyes staring into the sky. Things which cannot be told – nor dreamed. How men held on, each one knows, - not I. But manhood commands admiration.

*

Stout called the Gettysburg address “America’s greatest sermon.”

Scholars have rightly praised the literary qualities of Lincoln’s brief address at Gettysburg as a new sound in American rhetoric. But in American memory, it became much more. It became the sacred scripture of the Civil War’s innermost spiritual meaning. Central to that meaning was the revolutionary principle, always in need of implementation, that “all men are created equal.”… Lincoln presented a redemptive republic wedded to an idea in timeless form. As long as the idea survived, so too could America be assured that this “government of the people, by the people, for the people, shall not perish from the earth.” (Stout, p. 270)

*

American Congregational minister Horace Bushnell wrote, in 1863, in an essay entitled “The Doctrine of Loyalty”:

How far the loyal sentiment reaches and how much it carries with it, or after it, must also be noted. It yields up willingly husbands, fathers, brothers, and sons, consenting to the fearful chance of a home always desolate. It offers body, and blood, and life, on the altar of its devotion. It is a fact, a political worship, offering to seal itself by a martyrdom in the field. Wonderful, grandly honorable fact, that human nature can be lifted by an inspiration so high, even in the fallen state of wrong and evil.

Not only does this validate Lincoln’s dream of a

civil religion, it reiterates war – in its redemptive guise – as the province

and glory of males, of “husbands, fathers, brothers, and sons.”

*

A Richmond

Daily Whig editorial (1863) only serves to reiterate the connection between

masculinity and war in nationalist discourse, as well as the separation now

possible between manhood and Christianity:

The glory of Athens and Sparta were acquired by making every man a soldier, and considering non-combatants as drones in the national hive… No simpler principle, no dearer homes, no fairer land were ever fought for, bled for, died for than hang upon the issue of this conflict. Natal rights and native land, hereditary titles to property, the immunities of free citizenship, the sanctities of the hearthstone, the appealing voice of innocent and helpless womanhood – all can touch the hear the nerve the arm, cry trumpet-tongued all the brave and true men to fight this fight out to victory or death.

*

In 1863, N. H. Schenk, a Baltimore pastor who was

one of the few to break publicly with calls to sanguinary patriotism, wrote:

The ranks thinned to-day are filled to-morrow and the mournful dead march is directly changed into the gleeful quickstep. And as we grow indifferent to the value of life, we become proportionally indifferent to those great moral interests attached to life… we have suddenly become not only a military, but a warlike people.

*

Many went so far as to draw analogies between the soldiers’ deaths and the atoning work of Christ on the cross. In the North, a funeral for James T. Stebbins and Myron E Stowell, the pastor cried out: “We must be ready to give up our sons, brothers, friends – if we cannot go ourselves – to hardships, sufferings, dangers and death if need be, for the preservation of our government and the Freedom of the nation. We should lay them, willing sacrifices, upon the altar.” (Stout, p. 341)

*

From Lincoln’s second inaugural address:

With malice toward none; with charity for all; with firmness in the right, as God gives us to see the right, let us strive on to finish the work we are in; to bind up the nation’s wounds; to care for him who shall have borne the battle, and for his widow and orphan – to do all which may achieve and cherish a just, and a lasting peace, among ourselves, and with all nations.

*

From Chamberlain’s sermon eulogizing Lincoln after

the assassination:

Henceforth that flag is the legend which we bequeath to future generations, of that severe and solemn struggle for the nation’s life… Henceforth the red on it is deeper, for the crimson with which the blood of countless martyrs has colored it; the white on it is purer, for the pure sacrifice and self-surrender of those who went to their graves upbearing it; the blue on it is heavenlier, for the great constancy of those dead heroes, whose memory becomes henceforth as the immutable upper skies that canopy our land, gleaming withstars wherein we read their glory and duty.Yea, now behold a deeper crimson, a purer white, a heavenlier blue. A President’s blood is on it, who died because he dared to hold it in the forefront of the nation. The life of the president, who died in the nation’s Capitol, becomes, henceforth, an integral part of the life of the Republic. In Him the accidents of the visible flesh are changed to the permanence of an invisible and heroic spirit. (capitalization of Him in the original)

*

In an era of Western ascendancy, the triumph of Christianity clearly meant the triumph of the states of Christianity, among them the most powerful of modern states, the United States. Though religions have survived and flourished in persecution and powerlessness, supplicants nevertheless take manifestations of power as blessed evidence of the truth of faith. Still, in the religiously plural society of the United States, sectarian faith is optional for citizens, as everyone knows. Americans have rarely bled, sacrificed, or died for Christianity or any other sectarian faith. Americans have often bled, sacrificed, and died for their country. This fact is an important clue to its religious power. Though denominations are permitted to exist in the United States, they are not permitted to kill, for their beliefs are not officially true. What is really true in any society is what is worth killing for, and what citizens might be compelled to sacrifice their lives for. (Carolyn Marvin and David Ingle, in Blood Sacrifice and the Nation)

Cavanaugh's Complaint

In 2003, William T.

Cavanaugh, Catholic professor of Theology at St. Thomas University,

wrote an article for Commonweal, entitled “At odds with the pope, legitimate authority & just wars.” In that

article, he tells fellow Catholics that when the officials of the Roman

Catholic Church stood solidly against the US invasion and occupation of Iraq,

this official denunciation of the war should have compelled many Catholics to

oppose the war far more vigorously.

Cavanaugh’s argument is that if our confession of faith means what we

say it does, then when our allegiance to the Gospels and our allegiance to the

state is contradictory, allegiance to the Gospels (and the Church as the body

of Christ) takes precedence.

Cavanaugh’s

piece was directed at, among others, fellow Catholics who had embraced

neo-conservatism, and who stood against the Pope when he denounced the

war. Wrote Cavanaugh:

It is one thing to argue, on just-war grounds, against the overwhelming judgment of the pope and worldwide bishops, that the recent campaign in Iraq was morally justifiable. It is another thing to argue that the pope and bishops are not qualified to make such judgments. Neoconservative Catholic commentators and others have been trying to mitigate their embarrassment over being at odds with the pope on this issue by claiming that it is not really the church's call to make. Decisions about if and when we Catholics should kill should be left to the president. I believe this line of thinking is dangerously wrong.

One of

the neoconservatives was Archbishop to the Department of Defense (officially

called, “U.S. Military Services Archbishop) Edwin O'Brien, who was reassuring

Catholic soldiers – who had questions about a split allegiance to church and

state – that they could in good conscience accept the orders of President and

officers without having the means to judge the “justness” of the war. Te

absolvo.

Morality has been effectively outsourced.

The crux

of Cavanaugh’s opposition to this notion is the use of “just war” theory: theory that attempts to apply some standard

of justice to the conduct of war.

Cavanaugh does not say whether or not he accepts “just war” theory at

all; he is certainly conversant with the strengthening current of

trans-ecclesial Christian philosophy and theology that is pacifist, rejecting

Christian participation in war altogether (full discolsure - I am one of them.).

His point is that Pope Benedict and his neoconservative detractors were

using “just war” theory in very different ways.

The Pope

used the standards of just-war theory to argue for greater critical attention

to the background of the war, its motives, its methods, and its outcomes; and

thereby to hold off the option of war as long as humanly possible. The neoconservative Catholics – like all

warring nation-states themselves, used just-war standards as a checklist to be

satisfied before doing what one intended from the start – to go to war. Just-war theory was used as part of the

ramp-up. The neoconservatives – as part

of their argument – insisted that the state always takes precedence over the

church in certain matters (war being the key one); and moreover that church

members themselves are obliged, once the war decision is made, to “support the

troops,” a public relations euphemism for “accepting the war.”

Right-wing commentators have hastened to assert the right of the individual Catholic to dissent from the judgment of the pope and bishops on contingent matters of prudential judgment, such as the application of the just-war theory in a particular case. They are correct to do so. One need only cite the cases of Argentina and Rwanda to recognize that the judgments of bishops in matters of war and peace are not infallible. The problem is that we hear nothing from these commentators about any such right to dissent from the judgment of the state. In the United States there is no legal right to selective conscientious objection. The Catholic soldier cannot dissent from the president's judgment that this particular war is just. As for us Catholic civilians, are we allowed to dissent once the "call" has been made, and the president has issued his "final judgment" that the war is just?

Many contradictions inside the church create crises of conscience; and the church itself gives individual conscience a high priority, however…

According to traditional Catholic belief, a good conscience is a well-formed conscience. Moral formation involves becoming a follower of Jesus Christ through the gifts of the Holy Spirit available in the sacraments of the church and the practices of Christian charity. The formation of conscience should be done, insofar as it is possible, in communion with the whole people of God and its pastors. Of course, we should reject the idea of blind obedience to the political whims of individual bishops. When the pope and the bishops worldwide unite virtually unanimously in clear and repeated opposition to a war, however, the Catholic conscience should treat this matter with utmost seriousness. Pope John Paul II's opinion should count more than Donald Rumsfeld's or Bill O'Reilly's. At the very least, the Catholic should not simply abdicate moral judgment in this matter to leaders of a secular nation-state.

Cavanaugh will conclude in a way that is very satisfying to some liberals, at least those who for whatever reason opposed the Bush presidency and its wars (we now have Obama’s wars). The call to activism and the call to withdraw support will be welcomed by liberals. The call to be a community that stands apart from the world as witnesses, however, may be more troublesome.

The problem, I believe, is a fundamental inability of many U.S. Catholics and other Christians to imagine being out of step with the American nation-state. It should not be so difficult to suppose that the gospel does not always magically coincide with American foreign policy, or that Jesus has something to say that is irreconcilable with what Dick Cheney or Richard Perle thinks. Let us imagine that significant numbers of Catholics in the military--not everyone, perhaps, even just 10 percent--agreed with the pope and the U.S. Conference of Catholic Bishops that this particular war is unjustifiable, and decided to sit it out. Let us imagine that significant numbers of Catholic civilians – again, not necessarily everyone – did not agree that the president's judgment was final, and found ways to protest and refuse to support the war effort. Would we be witnessing the church overstepping the boundaries of its authority, or the dangerous mixing of politics and religion? No. We would be witnessing Catholics recovering their primary loyalty to Christ from the idolatry of the nation-state. And we would be witnessing, for once, the just-war theory being used to limit violence rather than justify it.

Pacifist Catholics and non-pacifist Catholics (and Christians more generally) ought to be able to find common ground in this discussion, out of plain good will first, but also because Christian pacifism of the sort some of us propound does not deny that force can be efficacious, even efficacious to achieve, in some cases, certain good outcomes. Our objection is to Christian participation in violence, and the positive obligation to seek reconciliation and make peace. When wars can be shown to be venal, stupid, and reckless, we can certainly voice our objection to those aspects of a war without being forced to make a ritual denunciation of war as the only “correct answer.” Venality and stupidity and recklessness are real things, and they can and do often make already bad situations far worse. Naming them as venality and stupidity and recklessness, and demonstrating the ways in which they are manifest is truth-telling.

Totality in War and Justice

Just-war doctrine for my confession began after the constantinian compromise, naturally, because then the church came to identify itself with the governing authorities and to set itself up in the manner of a shadow government. The doctrine has been adapted, but in doing so, the convictions of the church - and not the convictions of political rulers - have been the only thing to shift enough to make that adaptation possible.

By Augustinian standards, just-war is now incompatible with all modern war. The American Civil War just completed the modern process of subordinating church to state and to sacralizing the modern state itself. What makes modern war incompatible with Augustinian just-war doctrine is that modern war is total war or it is war exclusively in the interest of a state.

Saint Augustine of Hippo (354-430), a North African from what is now Algeria, was he first really pivotal philosophical influence on the constantinian church, in part because he wrote during the first days of the Christian state. It was not Constantine who made the Roman Empire officially Christian; it was Theodosius I, in the year 380. Constantine's famous conversion was in 337, after he interpreted winning a critical battle in his war to rule the Western Empire as a sign from the Christian God - here interpreted to have, like any pagan war deity or the like the Davidic war stories of the Hebrew Bible, delivered his enemies into his hands, and his conversion was rather like taking out a membership card as a show of gratitude. His subsequent actions reflected neither love nor charity, but a sanguinary Realpolitik. He did abolish crucifixion, substituting hanging instead, which is arguably a fraction less cruel in implementation. He also sponsored what was in many respects the founding conventions of the self-consciously institutional church. He died shortly after baptism, and was succeeded by a bloody coup d'etat. After much bloodletting in a destabilized empire, Theodosius took power in 379, and one year later declared the Eastern and Western Roman Empires to be Christian.

That self-conscious institutionalization of the church necessitated a Christian engagement with philosophy, and Augustine was part of that, a brilliant polymath who, like Constantine, saw the hand of Providence in Roman political power.

Men engage in wars, and wars are the productions of men - not women, even when a few participate. Historically, wars are man-stuff. Jesus set an example contrary to the kind of manhood that embraces power; but when the church aligned itself and its interests with the state, a new (old) kind of instrumentalism prevailed in the church, now firmly run by men. Augustine went with the flow, and with the flow at the top.

But he was not won completely over by the kind of slide into apathetic efficiency we see emerge during the American Civil War. The messages in the Gospels about peace, hope, charity, and love were taken very seriously, even when certain exceptions to them were being formulated in the service of power. Augustine honestly believed that war can be justifiably "necessary" (trickiest word there is, that one). He also believed it should be prosecuted by people who were virtuously motivated, and that armed conflict ought to be absolutely minimized.

He said that war can only be just it it meets two criteria: Jus Ad Bellum and Jus In Bello. Just in the decision to war, and just in its conduct.

He broke these categories down even further.

Jus Ad Bellum meant there was just authority, just cause, right intention, and last resort. That meant no off-the-books soldiers, no overreactions, no motive of revenge or gain, and no other option. You can measure today's wars by these criteria now if you like.

Jus In Bello meant proportionality, discrimination, and responsibility.

Proportionality means only enough force is used as is necessary to meet the criteria of just cause and just intention. "Shock and Awe" is not an idea that is compatible with proportionality.

Discrimination means discriminating between combatants and non-combatants, and (very important here) not targeting civilians. With Augustine, this was key. Under no circumstances were Christian soldiers ever to target civilians.

Responsibility:

A country is not responsible for unexpected side effects of its military activity as long as the following three conditions are met:Now you might say that war has evolved, and that we have to shade some of these criteria (like not targeting civilians), else we could no longer be effective in war; and I would say you're exactly right. WE certainly cannot. Bu the follow-on question is, why should a supposedly Christian criterion for just war be abandoned or modified because war has become more widely ruthless? We are just being towed along by this bullshit word - necessity - which comes to mean naked power attained by naked force. I don't get that anywhere in my Gospels.

(a) The action must carry the intention to produce good consequences.

(b) The bad effects were not intended.

(c) The good of the war must outweigh the damage done by it.

One of the things that Pope Benedict was saying about the Iraq War is that it was neither justly motivated, nor was it anything like the last resort. So there is a Jus Ad Bellum argument made, even though my own argument above is about Jus In Bello.

So what does it mean? I'm re-asking Cavanaugh's question here as we do the 4th of July in a couple of days. If the church says a war is unjust, should Christians follow their church or their state? I ask that question in the light of that history of the civic religion, because we are dealing with a real question of idolatry here.

Postscript

As the Civil War prefigured in so many ways, changes in the technology and doctrine of modern war have carried us into a new moral universe; or at least it is a new moral universe if you believe there is such a thing as a just war. My basic argument regarding Jus In Bello is that there is no longer any such thing, if there ever was. Civilian casualties now are accepted, and the number that are acceptable are even calculated into various algorithms. They are a subset of the planning category, "collateral damage," if you ever want an example of the pure evil that is latent in the neutralized speech of functionaries.

Bombs cannot discriminate. Period. But it's even more thoroughgoing than that. Augustine's idea that a good human heart could guide the sword never grasped the reality - the reality I have seen with my own eyes in the modern military - that the sword can drive every goodness out of one's heart. War is a practice that forms it participants more than its participants form it.

Stan, I was turned onto this post from an editor at the journal, Political Theology, and I'm stunned at what you've done here. Incredible work! - What is your last name? Where are you/have you studied? - You've done some great work here and I'd like to see it make the rounds in the theological social media circles I run in.

ReplyDeleteMany thanks for this piece. It'd terribly important, and terribly timely...

Thank you, Brian. My surname is Goff, and my background is not academic. I am 61, be 62 in November, and I wasn't even baptized until I was 56 years old. I have several past phases, including a career in the military, followed by a career as a socialist, prior to my conversion. People at Duke University had a real impact on me (I lived in Raleigh, 20 minutes from Duke), esp my pastor Greg Moore there, who introduced me to Stanley Hauerwas and Amy Lura Hall. I write some, more than just blogs, including a few books that seem odd to me now, a few years later. What I do have kind of an angle on is militarism - made it kind of a feral scholarly project for he last few years, and gender, too, because I can't tease militarism and masculinity apart yet - and it fits my own experience. I really appreciate your generous words, and thank you for taking the time to comment here; it's kind of a new blog.

ReplyDeleteThanks for the context, Stan. For want it's worth, your post haunted me today and I typed up a few remarks on my own blog: http://restorativetheology.blogspot.com/2013/07/technology-and-impossibility-of-just-war.html

DeleteI'm also immensely intrigued by your personal journey, Stan. I've followed you for some years on Feral Scholar, read your book Sex and War. Spoke to you about Detroit and gardening/farming some months ago.

ReplyDeleteI'm also am a Catholic, and I'm having a dickens of a time reconciling the us vs. them theology inherent in much of religion. I take my Christianity very seriously. Nowhere do I find Our Lord distinguishing who my neighbor is. I am in no way good and they are evil. The idea or concept of 'chosen-ness' is really difficult to understand ... theologically.

Anyway, this new blog of yours is great. I look forward to each of your Posts. I walk away a better person, if only because you've set my little grey cells to work.

Thanks, Stan...once again, you have given me justification that resisting the draft in 1971 was the proper course of action. It's taken a bit longer to clear the other baggage, but that's a lifetime project, eh?

ReplyDeleteVery well written. I am glad to hear you compare nationalism with religious faith. It is not something that is frequently done in modern America. But that's what nationalism is. Teresa, I would like to tie that in with what you are asking, regarding reconciling the "us vs. them" mentality that is inherent in religion. "Us vs. them," as a concept, doesn't require you to see yourself as being "good" and someone else as being "evil." You only have to see the "them" as being different, as in not belonging to your group or your label. You see yourself as being "saved" and them as being "unsaved" or at least "not yet saved" in much the same way that you see yourself as being "American," assuming that you are American, and the other person as being "not American." Perhaps they're British and this even happens to be a time when you are told to think that British people are okay. Even friends. Bear in mind, though, that that difference can be exploited. The word "them" or the word "unsaved/British" can be easily manipulated so that you see them as the opposing team if not outright the "evil bad people." Of course they're truly not the "evil bad people," but due to propaganda and perhaps even circumstances, your perception has changed. And it's all because you started off seeing them as different. But are they different? Is nationalism not a figment of the imagination? For that matter, is nation not a figment of man's collective imagination and the only thing that gives it any semblance of reality is that people are willing to enforce it? For my own part, I say the same of religion, but I am not here to discuss religion, although I don't claim one. I guess by me not claiming one I am using a bit of the "us vs. them" mentality as I am entertaining a false division but there is no need to worry. I will not let it be exploited were someone to want me to go to war with you. You see, there has never been a religious war. All wars have been about power. Even economic wars. Money is simply a metaphor for power and control. Religion, nation, flag, race, sexuality, even socioeconomic status... those are all merely ways in which we pick the teams. I am not trying to speak for Mr. Goff, but I talk to people all the time about this very concept, and this is the way it makes sense to me.

ReplyDeleteMichael, you are completely justified in skipping out of the draft in 1971. "If a law is unjust, a man is not only right to disobey it, he is obligated to do so." -Thomas Jefferson

For my own part, I wish I had seen things as correctly and maturely as you likely had in your youth. As of last week I have been enlisted for 17 years as I commit this minor act of treason with a dash of "Conduct Detrimental to the Good Order and Discipline of the Unit." Cheers.

I don't think I've made the claim that here are no differences between people, or peoples, or that I've claimed there is no occasion to describe "us" and "them." What Jesus taught, by his own example, is that these boundaries are permeable by love. Difference doesn't have to correspond to hierarchy.

ReplyDeleteI've been to Haiti 21 times, for example, and I can assure you that Haitian peasants, for example, are dramatically different from middle-class Americans. In certain discursive contexts, it is absolutely appropriate for this "blan" to refer to Haitian peasants as "them," and for a "paysan" to refer to my people as "them." These can be valid descriptive categories as long as we aren't concealing our own standpoints.

Money may be a metaphor (though I can see what's in my wallet, touch it), but I can apply it with great material force. As Hornborg said, general purpose money is what allows rain forests to be traded for Coca-Cola. And nation may be imaginary in some sense, but when I fly into the US, I have to pass through a phalanx of armed people, present documents, and understand that upon setting foot within a geographical boundary, I am subject to a particular set of laws that, again, are materially enforced (by people with guns, responding to a vast managerial apparatus comprised of hundreds of thousands of people).

N'est–ce pas?

Is it so? It is, in so much as there are certainly differences between people, although I would say that those differences are primarily superficial. I would argue that we have more in common than we do different. My argument stating "But are they different?" was errant. Throughout the rest of my argument I obviously recognized that there were differences between people and between groups of people and I contradicted myself. Perhaps I should have asked the question, "But are they as different as we think they are?" and then brought attention to the common threads of humanity that can be seen across cultural, religious, racial, and socioeconomic divides. People will generally react similarly to one another, given certain situations, regardless of culture. You don't have to go to another country to experience these differences or similarities. In many cases, all you have to do is drive across town. What I'm saying is that these differences can be and are manipulated and exploited for other people's gain. You don't have to see many 1940's depictions of Japanese people or listen to very many running cadences to understand that.

ReplyDeleteMoney has no value until one is ascribed to it. That said, I suppose it's not completely metaphorical. It's made out of paper. You could burn it, as has been done for survival in desperate situations, thereby giving it some innate value. There have been many metaphors that have been applied with great material force. Words themselves are given a value, carry weight and power, and have even started wars. We wouldn't write books, or burn them, if metaphors provided no material force. I suppose "Man cannot live on bread alone," has an application even here.

Regarding nations, the fact that large amounts of people imagine them and are willing to enforce their policies, force being the root of the word, doesn't mean that they aren't imaginary. There is no real boundary between Canada and the United States. No real boundary between say, New Mexico and Arizona. No boundary between counties, cities, or your property and your neighbors, barring the presence of a fence or river. So, are those boundaries there? Only in the sense that we, as a group, choose to recognize them. It's like natural rights. Everyone is born with them. It's just that some people allow others to exercise them and some don't. My girlfriend and three children live in England. I live in the United States. I understand very well the hoops through which we have to jump to jump from one hunk of rock that someone has foolishly claimed ownership of to another. Ownership itself is imaginary. The land that we name (ascribe a word to) the United States has only been "The United States" for a very short time. And it will only be so for a short while longer. Our claim of ownership of it changes it in no way, whatsoever, and is indeed, not only imaginary in a sense, but in fact. They are materially forced and enforced, but they are no more real than words and only attain a value that can be popularly recognized. Nations themselves choose to recognize or not recognize each other.

" National boundaries are not evident when we view the Earth from space. Fanatical ethnic or religious or national chauvinisms are a little difficult to maintain when we see our planet as a fragile blue crescent fading to become an inconspicuous point of light against the bastion and citadel of the stars."

-Carl Sagan

So yes, these things are materially enforced but they are nonetheless imaginary.

Cheers, sir. I am appreciative of the discussion and I hope you have a fine day.

@ Red Neckers:

ReplyDeleteI fought conscription and got out legally, and according to procedure, with a physical ailment (back problem). It was mild at the time, and with attention over the years, is still mild. That would have been irrevocably changed by the conditions of BT & combat (which I was destined for, having a 1968 lottery number of 24 & classified 1-A @ pre-induction physical).

For the record, I an not sure if this protocol (Final Medical Review) exists today.

For a few years, in the 60's, we had in this country something resembling a free press. Every night with my dinner, while in high school, I watched the unending parade of death & destruction from Vietnam. Growing up drowsing in a small industrial town in SW Oregon (now burnt out like the rust belt towns in the Midwest and East), I had not thought of much beyond what was presented to me by family and peers. To quote from one of Christopher Moore's books, a life of work in a mill, "beer, bowling, and a series of financed Fords". But I knew something was wrong, and went with my intuition. I learned more later.

@ Stan:

An illuminating picture in your post was the one on the (rather intense) fear of "Negro Rule" by Southerners. So---"equality" means "rule" by the "other"?? They must've known in their bones that the apartheid they created would quite possibly have the power to inspire an equal and opposite reaction.

Ain't no Love there...

You are lucky, Mike. I grew up in small town Kansas and was under the impression that everything was right. By following my intuition, I was wrong. Then again, I joined in peace (well, overtly it was peace) time. How would you recommend we pass on those lessons that we learn from times of overt war to the generations that will know the short lulls of peace? This is something that concerns me. We have to keep relearning the same lessons because the torch never gets passed. There is no "battle handoff" between generations regarding the horrible lessons we learn about invasion, occupation, and empire.

ReplyDeleteAfter all, "“The purpose of a writer is to keep civilization from destroying itself.” -Albert Camus

ReplyDeletePeople are having to rewrite what has already been written a thousand times.

@ Red Neckers:

ReplyDeleteYou just have to do it, period. Sometimes we think about these things for a long time, but when it comes time, just do it. There are times when it WON'T make you popular, but....Scott Nearing, born upper-middle class in 1883, described his life as a "series of secessions" from what was the "right" and "proper" thing to do in society at the time. and it ain't easy sometimes...we all like to be liked and have friends.