My friend, who teaches at a local college, needed to answer a call of nature after checking out, so he parked his cart and the two lads outside the restroom, went into the restroom long enough for a pee, flush, and hand-wash (he's pretty young, so that meant around a minute and a half - max), and came back out to take his comestibles and offspring home.

He was met by a red-faced woman who shouted that she was about to call the police!

The Police!?... my friend immediately ascertained that she was accusing him of child neglect.

"Relax," he advised her, concerned perhaps that she would have an aneurism. "I was only gone a second.

"If you turn your back for a second," she rebutted, still in an altered state, "your kids will be gone." They WILL BE gone! In a second.

"They were right on the other side of the door," he explained, but she was not to be pacified and continued her obstreperous rant, following him into the parking lot as he tried to make his escape, the boys by now also becoming agitated by her apparent derangement.

"Don't you watch TV?" she howled, whereupon my friend finally became short with her.

"No," he said. "I don't watch TV. It makes me paranoid."

This subtle rebuke was lost on her.

"Well," she hollered, blocking traffic in the parking lot, "You better start!"

By the time my friend was safely back in his car, his harrier glowering at him through his window, his youngest boy was asking why the police were coming for them, and were they about to be kidnapped?

The irony that she herself had caused the youngsters more distress than either had felt in a long time can only be matched that she demanded that my friend engage in the selfsame behavior, to wit, watching Lifetime Channel suburban, based-on-true-horror stories or the so-called news channels, that had turned her into a paranoid loon. To be a suitable parent is to walk through life - and to walk your kids through their lives - scared shitless.

The truth is the vast majority of missing kids in the US are kids who run away from home, closely followed by kids who are abducted by parents, relatives, or other who know the youngsters. Child snatches like the ones that make the big headlines and Lifetime TV movies number around 115 a year. With over 100 million youth under the age of 17, the odds of it happening to one of your kids is about one in 87,000 - about the same odds that you will date a super model or be killed by a volcano. Actually, you are more likely to date a super model or be killed by a volcano than that you will be snatched as a child by a total stranger bent on malfeasance.

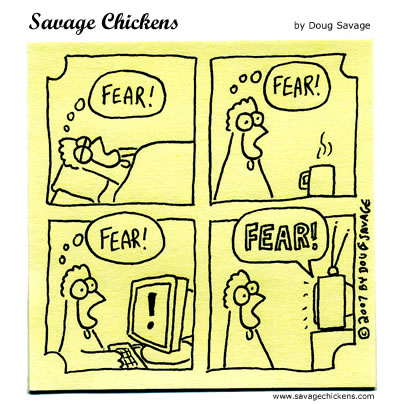

I can catch a story about it, though, about twenty-five times a week, with a cable subscription.

That's not to say nothing bad can happen to young people. Last I checked, life is unpredictable, full of nasty surprises and some nice ones, too, and people get hurt, abused, maimed, and eventually - this applies to us all - killed. That's right. Everyone is going to die, except those who died already. Everyone is going to suffer, who hasn't suffered already. Living involves risks, and unless you plan on going through your own life in bubble-wrap, not accepting risks is tantamount to a kind of delusion.

My friend's children were in far more danger during the ride to and from the grocery store than they were standing outside the men's room; and no one is suggesting they never ride along with Dad.

So there are real risks, statistical risks, and popularized risks.

A real risk. I am walking in a park. I peer under a rocky overhang, and there rests a large Eastern Diamond-back rattlesnake. So far, there is no real risk. I decide to approach the animal, within her strike range. There is a real risk, from a real snake, and arguably from my own lack of common sense. If I am bitten, I have participated in my own injury by taking a real (and unnecessary) risk. Most poisonous snake bite injuries in the United States, by the way, are on the hands, which tells you a story (often of stupidity), and most involve alcohol, which fleshes the story out even more.

There is statistical risk, which is not real, but a composite set of numbers. I am over 60, so my risk of heart attack is increased, even more at risk if I have something called a family history of heart disease. But both may be true, and a person may not have a heart attack. It's an abstracted risk. If I have a heart attack, the number spread is meaningless, too, because it is 100% sure that I have had a heart attack.

Then there are popularized risks, like the story above about the woman who started tripping out on my friend.

Then there is fear.

If I have a fear that a cornered rattlesnake might defend itself by biting me, that is a real fear, and I would be well-advised to act on it. Avoidance of a real risk. Nothing wrong with fear. It compels us to get away from situations that are actually quite dangerous. I cook every day. If I am about to transfer a pot full of boiling liquid, I fear it could burn someone if spilled, and I have spilled things before, so I am compelled to tell other people nearby that I am passing them with hot liquid in a pot. The appropriate warning is, "Hot stuff!"

If I have a fear of statistical risk tables, I will begin to obsessively measure myself against them, presumably to avoid pain and death. Am I too fat, too thin, drink too much milk? Do I have an ominous "family medical history"? Is my immune system optimal? Is the frequency and consistency of my stool within normal limits? Am I accumulating too much "stress"? And what fear means here - a kind of fuzzy yet omnipresent fear - is that I will pay experts to interpret my statistical risk factors and stay on top of these things, because I need to avoid pain that may happen and death that certainly will happen (though I must think and behave as if it won't, as if death is not inevitable).

There are risks, according to records, of paralysis from playing football. There are ways of avoiding that risk (or calculating it) related to technique and equipment. (Some people are obliged to handle rattlesnakes, and they prepare in advance for risks.) But if I don't play football, and if my kids don't play football, there are no risks... from playing football.

My statistical risk analysis above, where we compare death by volcano, dating a supermodel, and being kidnapped as a child, is concocted to make a point, but it is utterly meaningless if you are an actual person who was kidnapped as a child, then went on to date a supermodel, and was finally killed by a volcano. A pretty racy outline for a novel. This stuff does actually happen to people, regardless of the odds played by insurance companies and the like, who are the only ones in a position to translate he numbers into something tangible... money... actually.

But statistical risk analysis had nothing to do with our freaked out woman running after a car in the Meijers parking lot. Her fears - which were the fuel for her control freakery - were motivated by popular risk, which is an incredibly potent politico-economic tool. You are more likely to be killed by a police officer than a terrorist, but when you turn on your wide-screen home-data-feed, you are inundated with stories - jammed in between ads to alleviate various risks, from bad breath to cancer to home invasions - about police saving people from serial killers and terrorists. Serial killers account for fewer than one percent of murders, the category is contestable, and your chance of being murdered in the US is one in 133, so... do the math. Unless you are killed by a serial killer, whereupon your risk is 100%. People who are tuned into a TV (Don't you watch TV?! Well, you should!") are very worried about terrorists, serial killers, child kidnappers and the like; and so they are far more likely to know all the ways to prevent child kidnapping, for example, even if the statistical risks are not foremost in their minds. The simulacra on the TV is more compelling than the numbers, but surprisingly, it is also far more compelling than lived experience - where these things never happen to the overwhelming majority of people.

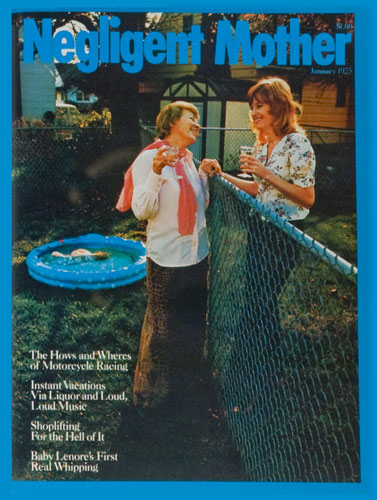

I'll argue, though, that this manufactured fear cannot stand alone, not as a psychological phenomenon, without an underlying interpretive framework (hermeneutics for you college kids) already in place, one that predisposes us to risk-management as a practice that constitutes itself also as worldview. We are a "safety" society, speaking now of metropolitan middle-classes. We believe in safety, safety first, being safe, because we are responsible, which means virtuous, and we prove that responsibility (and virtue) by attending to the problem of safety at all times. You don't leave your child on a shopping cart while you take piss, or that very act has cancelled all your safety merits with one big de-merit... and that woman running through the parking lot, hectoring a man and his kids is not exceptional, except that she is exceptionally committed to the norm. She is not abnormal, but over-normal, and she probably had a really bad day with something else altogether before spotting the un-virtuous parent.

I'll say something now to get myself in trouble with parents and "parenting" experts (sheesh!), and that is that I am glad I did not grow up now, but then. As I said above, my fellow kids, my siblings, and I got into stuff when we were kids, and we violated a shitload of safety calculations, and I would no more trade that for safety-first society than have my toenails trimmed with a chainsaw.

We dove off of cliffs into a quarry full of water. We hopped on slowed down trains to catch a free ride from St. James, Missouri, to Rolla, ten miles away, watched a movie, loitered for a while, then train-hitched back. We hunted rabbits with real guns, and with arrows. We camped out without adults, and sometimes just roamed around town all day on foot or bicycle (no helmets!). Drove a truck when I was twelve. Sneaked into farm ponds to catch a few fish or gather duck eggs. Caught snakes. Dumb stuff, too. I picked up cigarette habit young that was a bear to break.

It was a different time, and safety was already part of our mental landscape, but we were at a different stage... people told me that smoking was good for my digestion, and kids would chase DDT spraying trucks to cool off in summer. DDT was a safety measure back then, against he risk of the day - bugs.

We could have died, true. A few of us did. All of us will.

I wish we'd keep that foremost in our minds, because that sort of takes the absolutism out of safety-talk and a life of risk-management. No one gets out alive. And I'm not arguing for some carpe diem bullshit, which ends up being slacker hedonism or worse. I think there are virtues and vices, and that they are determined by practices; I just don't think safety is the measure of virtue and vice.

Our story, the story of Christians, of Jesus and his actions between baptism by John and the resurrection, is a story of taking risks. Even a popular fantasy - the Tolkien trilogy, written by a Catholic who studied Scandinavian mythologies - tells us that it is what we take risks about that determines our characters, not whether we are responsible risk managers.

Gollum tells Frodo at the entrance to Shelob's cave, "Go in, or go back." It may be a trap, but it is also true. Practical choice. Character. Virtue (in spite of and because of taking the risk). As a child, I had to make risks to take risks to demonstrate certain "virtues," which is called male socialization, but there was a certain buccaneer spirit involved because even then "rules" had replaced many choices, because I was a child. That's part of the safety-era, childhood - this invention that only came to pass recently and is still not universal.

It is a sentimentalized invention that young people are wedged into like a Procrustean bed, childhood, and it has come to pass in tandem with middle-class modernity. As one author put it, children became new beings who - for the time they existed as children - needed to be "perfect, protected, and tranquil." And safe!

This is an article of faith... more. This sentimental idealization of childhood is now so widely accepted here that any argument - like I am about to make - can be trumped by, "Would you rather your children be [choose one] (a) hurt, (b) maimed, (c) stolen, (d) molested, (e) kidnapped, (f) killed?"

In a sense, then, we are obliged to structure the environments of our children in a way that - before anything else - precludes absolutely any of these happenstances; which is an absurdity. No matter what we do, bad things will happen to people, including young people, due to circumstances beyond our control. And no human being has the latitude to do all the things that need doing by people when we eliminate risk.

I'm not saying we ought to dispense with safety. I'm sure that thousands of years before we became the safety-society, there were known risks and measures taken to avoid them. Look there, some ancient mother might have said to her five year old, that ram over there is mean, and if you stare at him, he'll butt you. Just as feasible is the five-year-old who disregards his mother and gets clocked by the ram. Learning can happen either way, but in the latter case there is a powerful memory associated with the safety rule. Our firmest knowledge is based in experience; and if you are to gain greater knowledge, then you will need to gain experience - none of which is risk free. The ram could kill the child. It's always possible.

God ensures that each of us dies.

Christians claim to follow a God who breached infinity to be a human being; and that this God-human showed people how to live in the face of suffering and death, how to know a contempt for he devil using the natural fear of death as a lever. Many of the first Christians were martyred.

Perpetua lived at the beginning of the 3rd Century in North Africa. She was a young woman who came from a pagan nobility. She was married with a baby, and she had a slave, Felicitas. Septimus Severus, the Emperor at the time, launched a campaign against Christians about the time that Perpetua converted, and with her, Felicitas, whereupon they became very close friends. She left a diary.

Perpetua and Felicity were arrested and tried, and her father appeals to her to recant her faith in order to preserve her and her child. She refused, nursed the child in prison, and Felicity actually gave birth in prison.

They gave their children away before they were executed in the arena. They, along with three other disciples - Saturninus and Secundulus, two freemen, and Revocatus, a slave - were scourged, then set out for the beasts - leopards, bulls, and boars. They gave each other the kiss of peace and submitted to the attacks of the animals, followed by the coup de grace from a soldier-executioner.

I cannot reconcile this story with what I see in a typical white, American, ostensibly Christian suburb...

A few tangential thoughts.

One of the things politicians and advertisers want to do is to freak you out. Freaked out people buy goods and services and elections to calm themselves, when those goods and services and elections are promoted as the solution to what they just freaked you out about. It's called demand creation, and safety is salable through fear.

One of the reasons we are all trapped in the child sentimentalization trap - which leads us to extend the infancy (the receptive dependency) of young people to well past puberty - is we have created an age-segregated society. Our kids are packed together with other kids their own age, where they participate in age-appropriate activities with a safety-adult presiding. Sometimes the safety-adult is also "teaching" them, which means coaxing them through exercises to do cognitive tricks, in various "subjects," even though almost all the subjects are "taught" and "studied" while sitting at a desk under enforced silence in a room that is plastered with two-dimensional cognitive trick posters.

Now I love cognitive tricks. Many are useful in the pursuit of may tasks; but that is not what happens in school classrooms under an age-segregation regime. Classrooms are Pavlovian enterprises, where the proper responses are drilled for the appropriate stimuli. Education is a product to make another product - a citizen-subject.

Meanwhile, six-year-olds are with other six-year-olds, nines with nines, twelves with twelves, and the only time they are fully engaged - not performing tricks for the teacher, that is - is when they get a break and can socialize with each other. In that context, they pay attention to the same stuff all humans do, but which schools reserve for college-level literature surveys: love, power, sex, death, and so forth.

By being engaged in only age-segregated environment, they not only come to a mutual suspicion of adults, who appear to them as little more than situational authority figures, they come to rely on one another for the kinds of wisdom-based authority that none of them has the experience to provide - particularly on the big issues like sex, power, love, death, etc. So what they learn to do is game the system, however that is understood and applicable.

These attitudes carry over into a society that has been generally infantilized by reliance on experts for virtually everything in a society that went from labor-segregation to task-segregation, systematically eliminating the kinds of skill-generalism required in earlier economies where householding was a significant aspect of the economy. Now, we just know when and where to plug into what expert or specialist, whereupon we exchange sum of money. The only thing at which we become well-practiced is exchanging money... and tapping on buttons and screens of course.

In the age-segregated schools, and any similarly authoritarian bureaucracy, you can see certain archetypes emerge: academic whiz, jock, the uber-kools, rebels (who need the status quo to define themselves), and so forth, including rule-enforcers and tattletales. The woman in the parking lot likely embodied one of the latter when she was being indoctrinated in her specific school. Everyone must find her or his niche in school, kind of the way they do in prison.

One of the things safety-society can't do is see the person that we are calling a child. We each see our own kids and those we know as people, sure, but the person living in that skin is not the sentimentalized being we created with the invention of childhood. I vaguely remember (it has been quite a long time ago) that I was just as restless then as I am now, just for different reasons. I also remember wanting to be like him... or her... or him - someone who was more experienced than me. I had a felt need for formation, for belonging, for participating, and for accepting the discipline of one who had some practical authority as a way of becoming more like them. That's missing to a large degree, which accounts for why a lot of young men end up liking the military - it forms people as apprentices and you know you belong (women, not as much, a different story).

Before the invention of childhood, kids were not packed together as kids. By the time many were five, they were already doing work around the house. I have watched peasant children work, and do so competently. Washing clothes. Carrying water. Working gardens. Tending animals. They have a gravitas and a dignity that I do not see among metropolitan children, a self-confidence without bluster. They will talk with you like an adult... or should I say, a person. When they have spare time, they will play with other children. But most of them are the understudies of one or more adults, apprentices to full participation in their communities.

Whatever modern society gained with mandatory, age-segregated "education" (a product they are required to consume), we have lost something important, too.

Danger is part of life. We invariably endanger ourselves and others. We can no more escape that than we can death, and for many of the same reasons; and to make safety the final measure of all things, or even most things, is a recipe for mindless conformity to a set of disembodied norms.

This is not in line with any formal thesis, I am just reflecting in text on all the facets of the safety society, and it reminds me of something Stanley Hauerwas wrote in the wake of the September 11, 2001 attacks that associates the safety society with war. It was addressed to American Christians...

At the heart of the American desire to wage endless war is the American fear of death. The American love of high-tech medicine is but the other side of the war against terrorism. Americans are determined to be safe, to be able to get out of this life alive. On September 11, Americans were confronted with their worst fear—a people ready to die as an expression of their profound moral commitments. Some speculate such people must have chosen death because they were desperate or, at least, they were so desperate that death was preferable to life. Yet their willingness to die stands in stark contrast to a politics that asks of its members in response to September 11 to shop.

Ian Buruma and Vishai Margalit observe in their article “Occidentalism” that lack of heroism is the hallmark of a bourgeois ethos. Heroes court death. The bourgeois is addicted to personal safety. They concede that much in an affluent, market-driven society is mediocre, “but when contempt for bourgeois creature comforts becomes contempt for life itself you know the West is under attack.” According to Buruma and Margalit, the West (which they point out is not just the geographical West) should oppose the full force of calculating antibourgeois heroism, of which Al-Qaeda is but one representative, through the means we know best—cutting off their money supply. Of course, Buruma and Margalit do not tell us how that can be done, given the need for oil to sustain the bourgeois society they favor.

Christians are not called to be heroes or shoppers. We are called to be holy. We do not think holiness is an individual achievement, but rather a set of practices to sustain a people who refuse to have their lives determined by the fear and denial of death.Hauerwas has said more than once that we have come to believe (talking of his fellow Americans now) that we shouldn't risk our children for our faith or convictions. That same sentimentalization that is applied to children is applied to the Gospels, and we end up with a bloodless and interchangeable devotion to "spirituality." All of us are infants, and the state is our parent. Try taking your kid out of school and see if it's not so.

The state is our parent, too, us "adults."

Which is why it is not okay to permit danger in the lives of your children (who are born with the fictional right to be "perfect, protected, and tranquil," but it is just fine to allow your eighteen-year-old to be killed in a war, or to kill in war and suffer that moral crippling. Safety, after all, comes with a price. Paradoxically, as Hauerwas explained, that price is the acceptance of the necessity for violence... as a condition of "being responsible."

Recently posted a longer piece on the American civil religion, linked here.

Again, no one is saying we should be stupid. The Haitians have a proverb: "A stupid person is a real thing."

We look out for those we love; and the injury or death of as child can be indescribably painful. I would never minimize that. But I need a theological perspective on this whole safety-thing and kid-thing, so I'll turn again to Dr. Hauerwas.

We are willing to worship a God only if God makes us safe. Thus you get the silly question, How does a good God let bad things happen to good people? Of course, it was a rabbi who raised that question, but Christians took it up as their own. Have you read the Psalms lately? We're seeing a much more complex God than that question gives credit for.

How ought we to be if we are people of Perpetua and Felicity, the Christians? And how are we forming young people... are we? Somewhere between schools where they learn conformity and authority, segregated youth culture where they are cut off from experience and wisdom, and mass media's double whammy of superficial and amoral entertainment combined with consumerism, kids are being formed.

This all just raises more questions, I know.

I just find myself applauding that dad who was unafraid to exercise common sense, a fact brought out by the woman who demanded, "Don't you watch TV?" And I've gotten glimpses of his kids. They are friendly, creative, adventurous, and self-confident youngsters, thanks be to God.

Just a few loosely strung-together thoughts.

You write well Stan. That was an enjoyable read.

ReplyDelete"On September 11, Americans were confronted with their worst fear—a people ready to die as an expression of their profound moral commitments."

ReplyDeleteThe paradox here being that these people were manipulated by profoundly AMORAL people (bourgeois?) who are willing to use up human beings to deny death as long as they possibly can. And pass it on to their descendents. After reading the quick and dirty review of "Occidentalism" on Amazon I see that this fits, and goes round and round.

PS---ever crash your bike on purpose when you were a kid? I can remember doing that....

ReplyDeleteThis comment has been removed by the author.

ReplyDeleteThis is classic Stan, and this issue is one that has occupied my thoughts for a long time. I can relate to this piece on so many levels. Not long ago, I got at call at the wilderness preserve where I work, and a nice gentleman asked me if I had specific knowledge of desert landscape nearby. It was a surprising question, because it was a somewhat remote area he was asking about and I just happened to have grow up there. I said I did, and he explained that he was working on a story that was going to take place in the wilderness, and he had some questions, would I mind meeting him? Sure I said. The next day, I met up with him and his associate, and they explained that he and his colleague were working on writing and producing a film that centered on kids having a right of passage journey. Very cool, I thought. They planed to advertise the film in a way that would help gather more support for organizations that do this kind of things with kids, Outward Bound, etc., etc. I've dedicated plenty of my life to this kind of pursuit, so I thought, double cool. So, what happens in the story? I asked. Well, they explained, they will follow the different kids and describe their backgrounds, some kids from the inner city, etc., etc., they meet up with their mentors, they bond, they go out for their solo time in the wilds, like a mini vision quest...

ReplyDeleteAnd then it turns out they've camped on the Indian burial ground, and it turns into a Poltergeist type story. Good Lord, tell me you're joking.

I explained that so far, it sounded like a terrible idea, and I had no idea how they were going to simultaneously gather support for outdoor education while giving kids even more scary bullshit to associate with nature than they already do. I did my best to explain that kids are already fed a steady diet of fear mongering ridiculousness when it comes to nature, and that many of us are trying our hearts out to offset that in any way we can, and our jobs are hard enough with out you working against us. Oh, the irony of them coming to the outdoor education community for help with a story like this. Your Collateral Damage piece was fresh in my mind.

"It will have to be done in the right way," they said, and they "weren't quite sure what that looked like yet.

I made it clear that from where I stood, it frankly looked stupid.

I IMDB'd them after they left. One of them is the executive producer form the film Crash, a film that won the academy award for best picture, and the other was screen writer who's star is rapidly rising. How funny is that?

In my favorite survival guide, Come Back Alive, Robert Young Pelton just takes the piss straight out of irrational fears with a little adventure quiz at the beginning. My favorite question and answers from it are:

The most dangerous creature in the world is? The mosquito.

The most dangerous wild animal in America is? The common deer.

The most dangerous place in the world is? Your home.

Most animal attacks in National Parks are caused by? Family Pets.

When attacked, the most powerful self-defense move is? Running away.