n

8. (Christianity / Ecclesiastical Terms) Christian theolthe creation of a sacrament by Christ, esp the Eucharist

I can only handle - according to Dunbar - about 150 I-care-you-care relationships… for the simple reason that this number reaches certain cognitive limits that may be organic, and because there is simply not enough time for more without diffusing the quality of all relationships.

Obviously, the number is fuzzy, because with changes in culture come changes in relationships – think Facebook and all your "friends" there - so there’s that shifting boundary in addition to existing cultural variability – and relationships themselves are difficult to define precisely because they are not quantifiable.

One could go on and on about what is imprecise about this claim; but imprecision is not sufficient to dismiss the general concept.

We do have some limits on our temporal and cognitive capacities to do the things we need to do to maintain our personal, embodied, unmediated relationships.

So if we want to use 150 as a hypothetical constant, and it turns out to be – as it likely is – variable across some range, then the range itself is a valid premise for further fuzzy conclusions… again, whose fuzziness is not sufficient to dismiss them.

The next premise is that the break between strong and weak bonds, that is, between kinship/friendship and utilitarian relationships, is a break where mutual care is often replaced as a basis for the relation by a structural suspicion for many instrumental relations.

I once had a retail manager tell me, "The customer is the enemy." In a sense, this is true. The seller and buyer are each pursuing antithetical interests in that the seller wants the most money for a sale, and the buyer wants to pay the least. That these contacts have been rendered cordial and courteous on the surface, doesn't change the structural antagonism.

In late capitalism, even that antagonism is highly mediated, because the actual sellers are often stockholders, and some poor working person represents them to buyers; the worker is in a structural antagonism with the stockholders, who are mediated by a supervisor who is paid to be the heavy, and who is also in a structural antagonism with both her boss and her subordinate. And the buyer is in an additional structural antagonism with the sellers, who use manipulative advertizing to create desires to separate the buyers from some cash. So it goes.

The way we deal with structural antagonism is through law, which upholds property entitlement and contract, but law is not the subject of this reflection - except as a subset of the category "institution."

What Dunbar is telling us, without intending to, is that beyond a certain threshold of scale in human relationships, person-to-person relations are no longer sufficient to deal with contingencies shared by the whole community. A different kind of relation is created by the emergence or appointment of a social apparatus to order relations between people, many of whom do not know or care for one another. Peopled by bosses, administrators, and managers, this apparatus of social control - which on one hand can serve the community - has displayed a tendency in all its guises throughout the ages to consolidate its control in ways that create an arena of power that is over and above the administered community.

Management, by definition, homogenizes and objectifies the community. Management is by its very nature utilitarian. The larger the community (scale again), the more management time that is devoted to conflict management, which management deals with by making policies, rules, or laws. Human beings are defined by what each of them has in common, reducing and abstracting them. In this process, the law trumps both the individual standing before the law and - in liberal law, especially - the actual shape of justice that appears in any contingency before or outside the law.

A boss, an administrator, a manager or even a specialized conflict resolver will always put systems and rules before love, whether that love is storge, philos, eros, or agape. In fact, love is antithetical to the foundation of rule-based relations. Managers are the caretakers of impersonality, invested personally in impersonality; and that impersonality accrues power to itself over and against the embodied person. This is especially true in late modernity, with its tremendous institutional scale and layering, underwritten by a fundamentally Hobbesian episteme that claims structural antagonism as human nature all the way down to individual persons, then fulfills its own expectations by codifying them into law.

Long story short.

The smaller the community, the more likely it can get things done and solve problems without a managerial layer, and without relying on formal rules.

Twenty friends do not need a contract signed to get together at one of their houses to build a garden on a weekend. Food and beer might help, but established rules are pretty much unnecessary as long as there is shared language and culture.

20,000 people in a town will need rules and management, but that management is more accountable and known in that community than in a city of 500,000, or moreso in a state, where not only greater numbers but geographic dispersion further depersonalize management - which is institutionalized, that is, organized according to some formula with a set of policies and a division of labor.

While a body occupies each position within the managerial division of labor, the knowledge and sensitivities and personal history of that person are secondary to the requirements of the job - making the actual person theoretically interchangeable. The institution contains embodied persons, but it is comprised of things without bodies - rules and positions, structures and functions.

In the United States of America, for example, the presidency is a job position, and it is quite simply not possible for any person who doesn't conform to the basic expectations built into that job to occupy that office. There will be no President who shuts down the military-industrial complex, who defies the consensus of the bond traders, or who argues for policies like "maximum wage," single-payer health care, or other left-liberal fantasies; because there are too many layers and public-private interlocking directorates, at that scale, who mediate each step of the selection process prior to elections. This is stability because it is impermeable to the agency of individual persons or even small groups of activists. Even those who are "inside" the system, including the President, are incapable of overcoming the stability of scale.

*

Disses

Many people are familiar with Max Weber's work on bureaucracy, which describes institutional disembodiment (in bureaucracy) alongside a metaphysical disenchantment - the world losing its sense of mystical wonder, places losing their sacred status.

Karl Polanyi discussed some the same phenomena with an eye to disembedding - the easier separation of people from place.

We just looked at how institutions can drive a mediating wedge between person and body by replacing persons with positions, disembodying us as the institutions disembody themselves.

Disenchantment is a term used by sociologists to mean a loss of the sense that the material world is sacred or mysterious. Weber describes this process ambivalently; but Carolyn Merchant in her book, The Death of Nature, provides a history of that de-sacralization of nature by the "fathers" of the Enlightenment. Merchant also relates this disenchantment - correctly, I believe - to the massive damage we are collectively doing to our environments and the whole biosphere. Prior to the Enlightenment, for example, mining was a disreputable practice, and the idea of strip-mining would have been unthinkable. The objectification of nature, the reduction of nature to mere matter and energy without meaning, that was accomplished by the elevation of natural science to a totalizing truth claim, was the prerequisite for those kind of practices that are now common and commonly destructive, with general purpose money as an accelerator.

Disembedding refers to the relocation of people from familiar surroundings, a network of non-market relationships, and a direct participation in the community into an impersonal world more determined by money, market abstractions, and industrial monoculture. Polanyi said we are re-embedded in that more impersonal milieu, where the market rules as the only form of economy, and where we are now captive to that market. We live in a society where nearly everything has been converted into a commodity, including ourselves.

Disembodiment, here, refers to the way that modern ideas and modern language, under the hegemony of institutions, treat the body as an alienable object and create the idea in the minds of actual persons that they must experience the body through the many mediations of institutions that thrive in a disenchanted and disembedding world. We know our bodies now as instruments, which are organized into systems, which are intelligible only through science, medicine, and therapy - the key similarity between each being they are mediating institutions.

Internal External

Complex human practice - whether it be a craft or a sport or a science or a religion - requires an institution to carry that practice across time and generations. The institution is not synonymous with the practice. The governing body of the NFL does not actually play football, the coaches and players do.

Only the practitioner can experience the satisfactions in mastery of a practice. The research scientist who loves her work gets a kick out of her discoveries, and she enjoys knowing and exercising the disciplines of that practice, aside from considerations of salary and prestige. Philosopher Alasdair MacIntyre calls these inhering practical satisfactions "internal goods." Salary and prestige are "external goods," those goods that do not inhere in that particular practice.

I am a huge fan of MacIntyre, but I am not sure this generic characterization doesn't conceal as much as it reveals; because this internal/external contradiction only describes one aspect of institutionalization. It does not deal with the disembodiment that is necessary for modern institutions to function, or with the scale-implications of Dunbar, and how those implications impact relations between persons, or even how we understand ourselves. There is truth in it, but the critique of institutions qua institutions doesn't go far - nor should it, because MacIntyre was writing primarily about virtue ethics, and a detour through institutional disembodiment would have been a distraction.

External goods in the institutional setting create the conditions for corruption, because they concentrate power and provide a gateway to unethical opportunities.

The person who worships sincerely experiences an internal good. When I attend Mass, and we receive the Eucharist, that internal good is supported and sustained by the church. Yet the same church that sustains the practice, and that produces a St. Francis or a Hildegard of Bingen or the transformation of an Oscar Romero, can also produce a massacre at Beziers or a Torquemada or the cover-up of sexual abuses.

But my hypothesis here is that something else about institutions prefigures these institutional crimes and abuses, more related to scale and the layers and permutations of mediation that characterize greater scale, and a peculiar kind of disembodiment that we all - speaking here of modern or "postmodern" metropolitans - take for granted.

Word Made Flesh

I believe that God's word and God's love became flesh, that God breached infinity to take form in the womb of a young woman, and thereby sanctified the flesh.

Ivan Illich gave an especially beautiful account of what this means in his interviews - just prior to his death - with David Cayley, now published in the book, Rivers North of the Future.

Illich described how the institutions of modernity have separated us from our own bodies and consolidated that separation (as a "good") in the mind of the person with an implanted (educated) compulsion to optimize her body. I am punning when I point out that Illich summarized this process as corruptio optimi quae est pessima, or "the corruption of the best is the worst." Nonetheless, the etymology of the verb "optimize" does connect it to Illich's use of the optimi-pessima polarity.

Illich wrote a pamphlet back in the 70s, called Medical Nemesis, about the growing institution of medicine, and how this "radical monopoly," as he called it, disembodies persons - how it has trained modern metropolitans to submerge the actual experience of embodied being - of our moist, heaving, noisy fleshiness - into an obsession with the body as a system of systems, which have to be managed by a little internalized panopticon that engages in a practice called - in the ugly language of the bureaucrat - "risk management."

In Rivers North of the Future, Illich explained:

Barbara Duden, who undertook a history of the experience of pregnancy in he book, Disembodying Women, sounds the same note about risk management, and shows how women have been singled out for particular kinds of risk management, especially as it relates to pregnancy, where what was once the purview of women has been turned over to doctors (mostly still male, and part of a 'masculine' establishment). Ultrasound, as it were, has fulfilled the promise of Sir Francis Bacon - the grand inquisitor of modernity - who spoke of nature as a female, and of a kind of tearing open:

Duden describes a pregnant Puerto Rican immigrant woman who has just arrived in New York City, and who is undergoing a bewildering medical screening.

A Modern Dilemma

Another book I recommend is Susan Bordo's 1992 study of "eating disorders," Unbearable Weight. In the book, she focuses on the "body image issues" that are typically studied by feminists who are interested in the the way women internalize social expectations about the bodies of women.

More and more, young men are being pulled into the manufactured expectations of the body as a sexual commodity, but women are especially captured by the valuation-by-appearance trap. Again, the body is understood as a project, the object of various interventions for the purpose of optimization (to what purpose is seldom asked, so axiomatic has this attitude become). Along with the doctor, we now need a well-appointed gym - perhaps with a personal trainer - where we can shape those glutes, tighten those tri's, and flatten those abs.

The modern dilemma is that we are simultaneously disembodied by an internalized critical gaze and forced to obsess about the condition and appearance of our bodies.

We measure our foods on calorie charts and glycemic indexes - seeking just the right amount of Omega-3 fatty acids or anti-oxidants or fiber. We pay attention to our bodies obsessively, attending to every sensation, every change in signs, the color of our urine, the consistency and frequency of our stool. We can no longer look at that fresh, hot loaf of bread from the oven without considering the risk of too many "carbs," or the potential catastrophes resulting from the melting butter. We have lost that unmediated joy that comes from biting into the hot, buttered bread, the explosive fragrance of the yeast, the crackle of the crust.

We are monitoring for risks instead, as if we can or ought to discern every possible strategy to extend our monitored lives... as if we aren't going to die, or we oughtn't suffer, or as though suffering itself is the enemy, held at bay by the phalanxes of experts that surround our anxiety. (Anxiety may be the most pointless kind of suffering... as Jesus pointed out.)

I write this now, and yet I am as much the captive as anyone, occasionally seeing myself in the mirror (a demonic device that makes what is forward backward!), discomfited against my will at how I am aging. And it needs to be said, to avoid the impression that I am criticizing those of us who in various ways (perhaps all of us) engage in these disembodying and obsessive practices. Modern society makes us sick in myriad ways; and we are forced - in some respects - to find ways to counteract the ways we have been made sick by our environment and our culture. A woman may not want to be particular about her appearance, but if she needs a job, for example, in order to pay bills, sleep indoors, and eat, then she finds herself compelled to conform to certain norms. Even while we can imagine the haptic consciousness of people in the past, we cannot extricate ourselves from our own culture (another kind of disembodiment in the liberal imagination). And the ability to escape from norms in this society, it needs to be said, is often as not, an exercise of power and privilege - something I have seen again and again among well-to-do "bohemians."

In an age when people are disembedded from any community that might discern the good from the actions of a person, and how those actions relate to the good of the community, we are left adrift, alone, competing with the other Hobbesian creatures, only to be captured by these manufactured anxieties. The body has been isolated - an alienable object managed by an acquisitive ghost; and here we stand, each of us, the "prisoners of addiction and envy," unbound from belonging, and re-bound by our commodification, our inability to simply be an unself-conscious body - vigorous today, sad tomorrow, relaxed at one point, sick another - an animal nature, a fleshy nature - sanctified in the belly of Mary.

I wrote a little rant a few days back about being fat - and this, too, is part of modern institutional disembodiment, of the disembodiment manufactured by weight-loss products, by medical weight charts, by image-bombardment designed to bring our bodies under critical review in the most gnostic way possible - we are indeed become a ghost in a machine.

Now I will close - knowing I have not pursued any central thesis with any kind of discipline - with a quote from Susan Bordo's book; and I will leave the reader to his or her thoughts. I may only be doing a multiple book review about body-history.

1. the act of instituting

2. an organization or establishment founded for a specific purpose, such as a hospital, church, company, or college

3. the building where such an organization is situated

4. an established custom, law, or relationship in a society or community

5. (Economics, Accounting & Finance / Stock Exchange) Also called institutional investor

a large organization, such as an insurance company, bank, or pension

fund, that has substantial sums to invest on a stock exchange

6. Informal a constant feature or practice Jones' drink at the bar was an institution

7.

(Christianity / Ecclesiastical Terms) the appointment or admission of

an incumbent to an ecclesiastical office or pastoral charge

8. (Christianity / Ecclesiastical Terms) Christian theolthe creation of a sacrament by Christ, esp the Eucharist

institutionary adj

an organization or establishment founded for a specific purpose

Why do we need institutions?

*

Dunbar

"A[n institution] appears at first sight an extremely obvious, trivial thing. But its analysis brings out that it is a very strange thing, abounding in metaphysical subtleties..."

Take "Dunbar's number,"

for example, an idea of anthropologist Robin Dunbar. Dunbar’s number –

150 as a fuzzy constant – is the number of significant relationships a

person can manage without emotional cut-outs who attend to

administration, management, and conflict resolution. If you are my

hiking buddy twice a week and my second cousin, we have a primary

relationship. If you are my insurance agent or my boss, we have a

formal, rule-mediated relationship. If you are a clerk at the drug

store, and we don't even know each others names, we have a structurally

transient relationship.

I can only handle - according to Dunbar - about 150 I-care-you-care relationships… for the simple reason that this number reaches certain cognitive limits that may be organic, and because there is simply not enough time for more without diffusing the quality of all relationships.

Obviously, the number is fuzzy, because with changes in culture come changes in relationships – think Facebook and all your "friends" there - so there’s that shifting boundary in addition to existing cultural variability – and relationships themselves are difficult to define precisely because they are not quantifiable.

One could go on and on about what is imprecise about this claim; but imprecision is not sufficient to dismiss the general concept.

We do have some limits on our temporal and cognitive capacities to do the things we need to do to maintain our personal, embodied, unmediated relationships.

So if we want to use 150 as a hypothetical constant, and it turns out to be – as it likely is – variable across some range, then the range itself is a valid premise for further fuzzy conclusions… again, whose fuzziness is not sufficient to dismiss them.

The next premise is that the break between strong and weak bonds, that is, between kinship/friendship and utilitarian relationships, is a break where mutual care is often replaced as a basis for the relation by a structural suspicion for many instrumental relations.

I once had a retail manager tell me, "The customer is the enemy." In a sense, this is true. The seller and buyer are each pursuing antithetical interests in that the seller wants the most money for a sale, and the buyer wants to pay the least. That these contacts have been rendered cordial and courteous on the surface, doesn't change the structural antagonism.

In late capitalism, even that antagonism is highly mediated, because the actual sellers are often stockholders, and some poor working person represents them to buyers; the worker is in a structural antagonism with the stockholders, who are mediated by a supervisor who is paid to be the heavy, and who is also in a structural antagonism with both her boss and her subordinate. And the buyer is in an additional structural antagonism with the sellers, who use manipulative advertizing to create desires to separate the buyers from some cash. So it goes.

The way we deal with structural antagonism is through law, which upholds property entitlement and contract, but law is not the subject of this reflection - except as a subset of the category "institution."

What Dunbar is telling us, without intending to, is that beyond a certain threshold of scale in human relationships, person-to-person relations are no longer sufficient to deal with contingencies shared by the whole community. A different kind of relation is created by the emergence or appointment of a social apparatus to order relations between people, many of whom do not know or care for one another. Peopled by bosses, administrators, and managers, this apparatus of social control - which on one hand can serve the community - has displayed a tendency in all its guises throughout the ages to consolidate its control in ways that create an arena of power that is over and above the administered community.

Management, by definition, homogenizes and objectifies the community. Management is by its very nature utilitarian. The larger the community (scale again), the more management time that is devoted to conflict management, which management deals with by making policies, rules, or laws. Human beings are defined by what each of them has in common, reducing and abstracting them. In this process, the law trumps both the individual standing before the law and - in liberal law, especially - the actual shape of justice that appears in any contingency before or outside the law.

A boss, an administrator, a manager or even a specialized conflict resolver will always put systems and rules before love, whether that love is storge, philos, eros, or agape. In fact, love is antithetical to the foundation of rule-based relations. Managers are the caretakers of impersonality, invested personally in impersonality; and that impersonality accrues power to itself over and against the embodied person. This is especially true in late modernity, with its tremendous institutional scale and layering, underwritten by a fundamentally Hobbesian episteme that claims structural antagonism as human nature all the way down to individual persons, then fulfills its own expectations by codifying them into law.

Long story short.

The smaller the community, the more likely it can get things done and solve problems without a managerial layer, and without relying on formal rules.

Twenty friends do not need a contract signed to get together at one of their houses to build a garden on a weekend. Food and beer might help, but established rules are pretty much unnecessary as long as there is shared language and culture.

20,000 people in a town will need rules and management, but that management is more accountable and known in that community than in a city of 500,000, or moreso in a state, where not only greater numbers but geographic dispersion further depersonalize management - which is institutionalized, that is, organized according to some formula with a set of policies and a division of labor.

While a body occupies each position within the managerial division of labor, the knowledge and sensitivities and personal history of that person are secondary to the requirements of the job - making the actual person theoretically interchangeable. The institution contains embodied persons, but it is comprised of things without bodies - rules and positions, structures and functions.

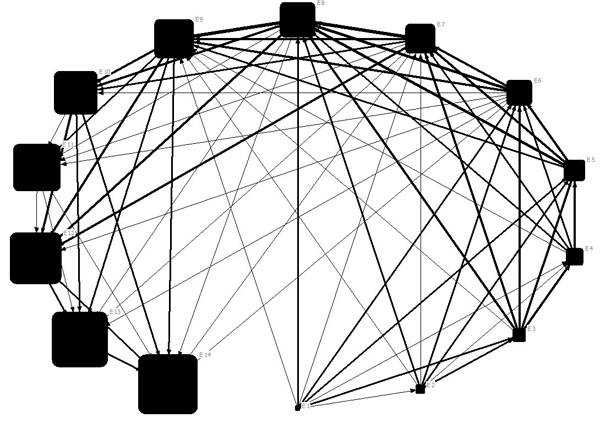

In the United States of America, for example, the presidency is a job position, and it is quite simply not possible for any person who doesn't conform to the basic expectations built into that job to occupy that office. There will be no President who shuts down the military-industrial complex, who defies the consensus of the bond traders, or who argues for policies like "maximum wage," single-payer health care, or other left-liberal fantasies; because there are too many layers and public-private interlocking directorates, at that scale, who mediate each step of the selection process prior to elections. This is stability because it is impermeable to the agency of individual persons or even small groups of activists. Even those who are "inside" the system, including the President, are incapable of overcoming the stability of scale.

*

Disses

Many people are familiar with Max Weber's work on bureaucracy, which describes institutional disembodiment (in bureaucracy) alongside a metaphysical disenchantment - the world losing its sense of mystical wonder, places losing their sacred status.

Karl Polanyi discussed some the same phenomena with an eye to disembedding - the easier separation of people from place.

We just looked at how institutions can drive a mediating wedge between person and body by replacing persons with positions, disembodying us as the institutions disembody themselves.

Disenchantment is a term used by sociologists to mean a loss of the sense that the material world is sacred or mysterious. Weber describes this process ambivalently; but Carolyn Merchant in her book, The Death of Nature, provides a history of that de-sacralization of nature by the "fathers" of the Enlightenment. Merchant also relates this disenchantment - correctly, I believe - to the massive damage we are collectively doing to our environments and the whole biosphere. Prior to the Enlightenment, for example, mining was a disreputable practice, and the idea of strip-mining would have been unthinkable. The objectification of nature, the reduction of nature to mere matter and energy without meaning, that was accomplished by the elevation of natural science to a totalizing truth claim, was the prerequisite for those kind of practices that are now common and commonly destructive, with general purpose money as an accelerator.

Disembedding refers to the relocation of people from familiar surroundings, a network of non-market relationships, and a direct participation in the community into an impersonal world more determined by money, market abstractions, and industrial monoculture. Polanyi said we are re-embedded in that more impersonal milieu, where the market rules as the only form of economy, and where we are now captive to that market. We live in a society where nearly everything has been converted into a commodity, including ourselves.

Disembodiment, here, refers to the way that modern ideas and modern language, under the hegemony of institutions, treat the body as an alienable object and create the idea in the minds of actual persons that they must experience the body through the many mediations of institutions that thrive in a disenchanted and disembedding world. We know our bodies now as instruments, which are organized into systems, which are intelligible only through science, medicine, and therapy - the key similarity between each being they are mediating institutions.

Internal External

Complex human practice - whether it be a craft or a sport or a science or a religion - requires an institution to carry that practice across time and generations. The institution is not synonymous with the practice. The governing body of the NFL does not actually play football, the coaches and players do.

Only the practitioner can experience the satisfactions in mastery of a practice. The research scientist who loves her work gets a kick out of her discoveries, and she enjoys knowing and exercising the disciplines of that practice, aside from considerations of salary and prestige. Philosopher Alasdair MacIntyre calls these inhering practical satisfactions "internal goods." Salary and prestige are "external goods," those goods that do not inhere in that particular practice.

Chess, physics, and medicine are practices; chess clubs, laboratories, universities, and hospitals are institutions. Institutions are characteristically and necessarily concerned with what I have called external goods. They are involved in acquiring money and other material goods; they are structured in terms of power and status, and they distribute money, power and status as rewards. Nor could they do otherwise if they are to sustain not only themselves, but also the practices of which they are the bearers. (MacIntyre, After Virtue, p. 194)MacIntyre's preoccupation in his book, After Virtue, is with the development of character and the exercise of virtues as an antidote to the corruptibility of institutions. In fact, he notes that the practice of running institutions may itself provide those internal goods to the proficient practitioner.

I am a huge fan of MacIntyre, but I am not sure this generic characterization doesn't conceal as much as it reveals; because this internal/external contradiction only describes one aspect of institutionalization. It does not deal with the disembodiment that is necessary for modern institutions to function, or with the scale-implications of Dunbar, and how those implications impact relations between persons, or even how we understand ourselves. There is truth in it, but the critique of institutions qua institutions doesn't go far - nor should it, because MacIntyre was writing primarily about virtue ethics, and a detour through institutional disembodiment would have been a distraction.

External goods in the institutional setting create the conditions for corruption, because they concentrate power and provide a gateway to unethical opportunities.

The person who worships sincerely experiences an internal good. When I attend Mass, and we receive the Eucharist, that internal good is supported and sustained by the church. Yet the same church that sustains the practice, and that produces a St. Francis or a Hildegard of Bingen or the transformation of an Oscar Romero, can also produce a massacre at Beziers or a Torquemada or the cover-up of sexual abuses.

But my hypothesis here is that something else about institutions prefigures these institutional crimes and abuses, more related to scale and the layers and permutations of mediation that characterize greater scale, and a peculiar kind of disembodiment that we all - speaking here of modern or "postmodern" metropolitans - take for granted.

Word Made Flesh

I believe that God's word and God's love became flesh, that God breached infinity to take form in the womb of a young woman, and thereby sanctified the flesh.

Ivan Illich gave an especially beautiful account of what this means in his interviews - just prior to his death - with David Cayley, now published in the book, Rivers North of the Future.

Illich described how the institutions of modernity have separated us from our own bodies and consolidated that separation (as a "good") in the mind of the person with an implanted (educated) compulsion to optimize her body. I am punning when I point out that Illich summarized this process as corruptio optimi quae est pessima, or "the corruption of the best is the worst." Nonetheless, the etymology of the verb "optimize" does connect it to Illich's use of the optimi-pessima polarity.

Illich wrote a pamphlet back in the 70s, called Medical Nemesis, about the growing institution of medicine, and how this "radical monopoly," as he called it, disembodies persons - how it has trained modern metropolitans to submerge the actual experience of embodied being - of our moist, heaving, noisy fleshiness - into an obsession with the body as a system of systems, which have to be managed by a little internalized panopticon that engages in a practice called - in the ugly language of the bureaucrat - "risk management."

In Rivers North of the Future, Illich explained:

[T]hat [experienced, fleshy] body, during the last fifty years, in my opinion, has been profoundly obscured, the ability of perceiving it maligned, and its remainders transformed into symptoms, which a doctor, if he is a good specialist, somewhere on the border of psychology, can classify. I have therefore come to the conclusion that when the angel Gabriel told that girl in the town of Nazareth in Galilee that God wants to be in her belly, he pointed to a body which has gone from the world in which I live.

I can study this disembodiment of the modern soma particularly well in medical interviews, but I can also study it by reflecting on the way in which my feet are disembodied when I move mainly on my behind. I was struck by the waitress in a quick food shop on the way from Philadelphia to State College who presented me with a choice of vitamins and other inputs which a man of my age and my constitution would need. And I remembered when I invited a historian of the body whose writings had impressed me to State College. When eh got there, he sat seven or eight of us down in a circle and said, Now, in order to be able to study body history, we must first visualize our interior. You know something about where your heart is and where your liver is from the charts in grammar school, now we'll feel and visualize and taste our heart, as if he were taking us on a trip through the innards of some mechanical device. And, in the most intense way, I think, this disembodiment happens through what we call risk awareness. If anybody should ask me what is the most important religiously celebrated ideology today, I would say the ideology of risk awareness - palpating your breast, or the place between your legs, in order to be able to go to the doctor early enough to find out if you are a cancer risk. Why is risk so disembodying? Because it is a strictly mathematical concept. It is placing myself, each time I think of risk, into a base population for which certain events, future events, can be calculated. It's an invitation to intensive self-algorithmization, not only disembodying, but reducing myself entirely to misplaced concreteness by projecting myself on a curve.

You asked me to speak about why it seems to me important, in relation to Christianity, to understand what the historical, the epochal sense of body is. And my answer is, because I know from my own conversations with people whom I meet, to whom I want to talk about the Incarnation, or the carnal side of faith, hope, and charity, trust in your word, hope in your answer, love, that the majority have no more sense of body. Or, if they do speak of body, it is in the New Age sense of a body which is an ideological construct interiorized through certain psychological techniques with which the person identifies.Body-System

Barbara Duden, who undertook a history of the experience of pregnancy in he book, Disembodying Women, sounds the same note about risk management, and shows how women have been singled out for particular kinds of risk management, especially as it relates to pregnancy, where what was once the purview of women has been turned over to doctors (mostly still male, and part of a 'masculine' establishment). Ultrasound, as it were, has fulfilled the promise of Sir Francis Bacon - the grand inquisitor of modernity - who spoke of nature as a female, and of a kind of tearing open:

For you have but to hound nature in her wanderings, and you will be able when you like to lead and drive her afterwards to the same place again. Neither ought a man to make scruple of entering and penetrating into those holes and corners when the inquisition of truth is his whole object.Duden refers to the scientific imaging of women's insides by medicine as "skinning" them. And she asks how this being "penetrated" by the scientific gaze has led women - in this case, pregnant women - to internalize this being opened up to the medical gaze in a way that disembodies them.

Duden describes a pregnant Puerto Rican immigrant woman who has just arrived in New York City, and who is undergoing a bewildering medical screening.

As she sat there, she was urged to accept a fetus. [She was previously in a state of hope for a baby. -SG] She was being bombarded with a dozen notions that together make up the conceptual framework of a slum pregnancy in New York: normal development, risk, expectancy, fetus, social security payments, and the like... I am trying to understand ... the difference the encounter with a professional makes for Maria and the degree to which it removes her from the way her mother experienced the body. Maria is given a graphic representation of something called a typical fetus, which assumes the notion of normality expressed in measurements, such as average weight and position. Maria must stretch her imagination to grasp these abstractions. The experience of her mother was more sensual, warm, touchable, familiar.When I was doing my Special Forces medical training in Ft. Sam Houston, Texas, we - like doctors - were trained using cadavers. Some were still together, albeit cut up so we could remove, handle, inspect, and replace the parts. Some were separated into pieces. A memorable one was a dead baby's head, sagitally cut so we could see into it like a cross-cut diagram with exposed tongue, palates, sinuses, cranial vault, the folds of the brain. With fiber optics and other innovations, we can look inside living people with a kind of anatomical voyeurism.

When a modern woman submits to this kind of procedure, she is forced to choose between two existential attitudes, aliveness or life: on the one hand, her aliveness, on the other, life that can added to other lives and managed. These works refer to two modes of existence, two kinds of consciousness that are not made of the same historical stuff. In the former, she feels and experiences because aliveness is simply her condition. In the latter, a scientificaly established state is imputed to her by the current experts. If the test operationally verifies a hormonal change, she can be said to carry "a life" and to begin a nine-month career as its ecosystem. (Duden, p. 53)Pregnant women now live in a world defined by "genetic risk profiles."

A Modern Dilemma

Another book I recommend is Susan Bordo's 1992 study of "eating disorders," Unbearable Weight. In the book, she focuses on the "body image issues" that are typically studied by feminists who are interested in the the way women internalize social expectations about the bodies of women.

More and more, young men are being pulled into the manufactured expectations of the body as a sexual commodity, but women are especially captured by the valuation-by-appearance trap. Again, the body is understood as a project, the object of various interventions for the purpose of optimization (to what purpose is seldom asked, so axiomatic has this attitude become). Along with the doctor, we now need a well-appointed gym - perhaps with a personal trainer - where we can shape those glutes, tighten those tri's, and flatten those abs.

The modern dilemma is that we are simultaneously disembodied by an internalized critical gaze and forced to obsess about the condition and appearance of our bodies.

We measure our foods on calorie charts and glycemic indexes - seeking just the right amount of Omega-3 fatty acids or anti-oxidants or fiber. We pay attention to our bodies obsessively, attending to every sensation, every change in signs, the color of our urine, the consistency and frequency of our stool. We can no longer look at that fresh, hot loaf of bread from the oven without considering the risk of too many "carbs," or the potential catastrophes resulting from the melting butter. We have lost that unmediated joy that comes from biting into the hot, buttered bread, the explosive fragrance of the yeast, the crackle of the crust.

We are monitoring for risks instead, as if we can or ought to discern every possible strategy to extend our monitored lives... as if we aren't going to die, or we oughtn't suffer, or as though suffering itself is the enemy, held at bay by the phalanxes of experts that surround our anxiety. (Anxiety may be the most pointless kind of suffering... as Jesus pointed out.)

I write this now, and yet I am as much the captive as anyone, occasionally seeing myself in the mirror (a demonic device that makes what is forward backward!), discomfited against my will at how I am aging. And it needs to be said, to avoid the impression that I am criticizing those of us who in various ways (perhaps all of us) engage in these disembodying and obsessive practices. Modern society makes us sick in myriad ways; and we are forced - in some respects - to find ways to counteract the ways we have been made sick by our environment and our culture. A woman may not want to be particular about her appearance, but if she needs a job, for example, in order to pay bills, sleep indoors, and eat, then she finds herself compelled to conform to certain norms. Even while we can imagine the haptic consciousness of people in the past, we cannot extricate ourselves from our own culture (another kind of disembodiment in the liberal imagination). And the ability to escape from norms in this society, it needs to be said, is often as not, an exercise of power and privilege - something I have seen again and again among well-to-do "bohemians."

In an age when people are disembedded from any community that might discern the good from the actions of a person, and how those actions relate to the good of the community, we are left adrift, alone, competing with the other Hobbesian creatures, only to be captured by these manufactured anxieties. The body has been isolated - an alienable object managed by an acquisitive ghost; and here we stand, each of us, the "prisoners of addiction and envy," unbound from belonging, and re-bound by our commodification, our inability to simply be an unself-conscious body - vigorous today, sad tomorrow, relaxed at one point, sick another - an animal nature, a fleshy nature - sanctified in the belly of Mary.

I wrote a little rant a few days back about being fat - and this, too, is part of modern institutional disembodiment, of the disembodiment manufactured by weight-loss products, by medical weight charts, by image-bombardment designed to bring our bodies under critical review in the most gnostic way possible - we are indeed become a ghost in a machine.

Now I will close - knowing I have not pursued any central thesis with any kind of discipline - with a quote from Susan Bordo's book; and I will leave the reader to his or her thoughts. I may only be doing a multiple book review about body-history.

The moral - and as we shall see, eocnomic - coding of the fat/slender body in terms of its capacity for self-containment and the control of impulse and desire represents the culmination of a developing historical change in the social symbolism of body weight and size. Until the late nineteenth century, the central discriminations marked were those of class, race, and gender; the body indicated social identity and "place." So, for example, the bulging stomachs of mid-nineteenth-century businessmen and politicians were a symbol of bourgeois success, an outward manifestation of their accumulated wealth. By contrast, the gracefully slender body announced aristocratic status; disdainful of the bourgeois need to display wealth and power ostentatiously, it commanded social space invisibly rather than aggressively, seemingly the commerce in appetite or the need to eat. Subsequently, this ideal began to be appropriated by the status-seeking middle class, as slender wives became the showpieces of their husbands' success.

Corpulence went out of middle-class vogue at the end of the century... Social power had to be less dependent on the sheer accumulation of material wealth and more connected to the ability to control and manage the labor and resources of others. At the same time, excess body weight came to be seen as reflecting moral and personal inadequacy, or lack of will. These associations are possible only in a culture of overabundance - that is, in a society in which those who control the production of "culture" have more than enough to eat. The moral requirement to diet depends on the material preconditions that make the choice to diet an option and the possibility of personal "excess" a reality. Although slenderness continues to retain some of its traditional class associations ("a woman can never be too rich or too thin"). the importance of this equation has eroded considerably since the 1970s. Increasingly, the size and shape of the body have come to operate as a market of personal, internal order (or disorder) - as a symbol for the emotional, moral, or spiritual state of the individual.

This comment has been removed by a blog administrator.

ReplyDelete